Processing the past

The uneasy legacy of racial research

In an extensive essay, Nature has been coming to terms with its own racist past.

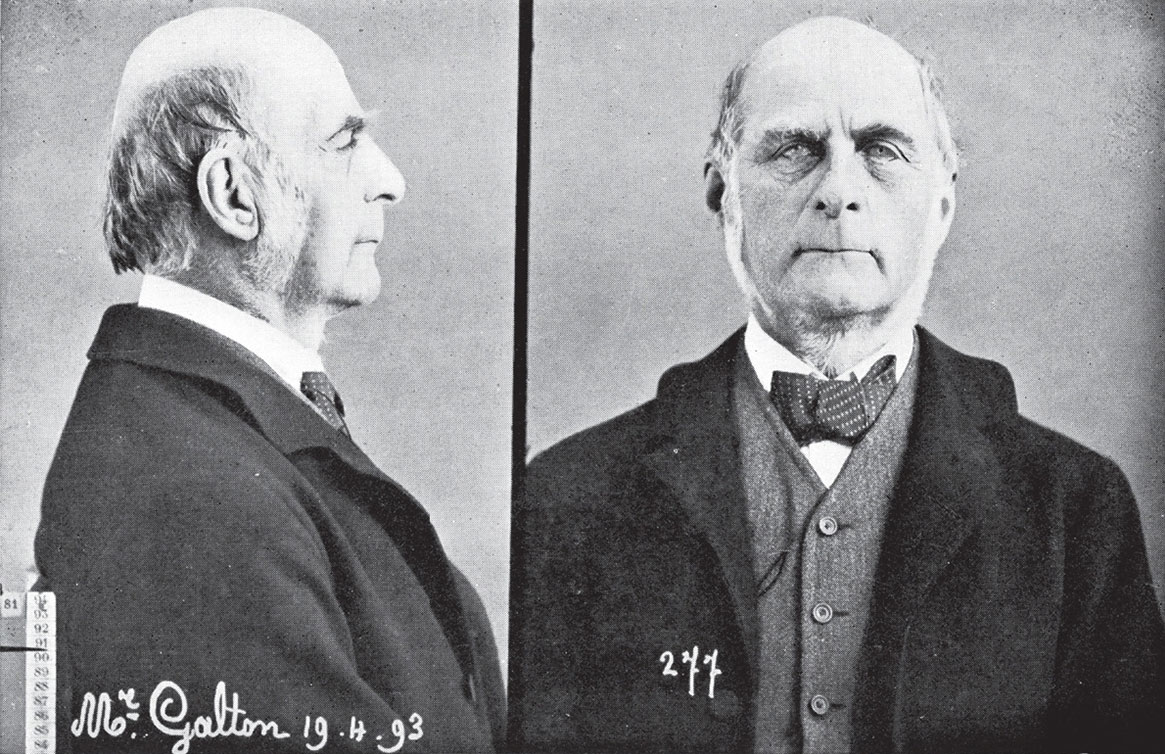

Francis Galton, the founder of eugenics, was photographed in Paris in 1893 when he visited Alphonse Bertillon’s Laboratoire d’identification criminelle. | Image: Paul D. Steward/Royal Statistical Society

The British polymath Francis Galton was responsible for numerous scientific advances in the 19th century, e.g., the use of fingerprints as a reliable means of identification. But he was also one of the initiators of eugenics and believed “that humanity could be improved by selectively breeding what he called the most worthy, intelligent, talented people”, as Nature now reports. In 1904, this British journal published an article by Galton entitled ‘Distribution of successes and of natural ability among the kinsfolk of fellows of the Royal Society’, in which he claimed that “exceptionally gifted families must exist, whose race is a valuable asset to the nation”.

Now this journal, which was founded in 1869, has published an extensive essay in which it comes to terms with its history. It also notes that its editor from 1919 to 1939, Richard Gregory, “published editorials with objectionable and racist views, such as one in 1921 that stated that ‘the highly civilised races of Europe and America have centuries of development behind them’”, while noting that “the less advanced races … are not likely to assimilate these ideals for some time to come”. Nature has concluded that it “regrettably played a part in casting the eugenics shadow” on those times.

Racist scientific research was also supported in Switzerland, even by the SNF, as Pascal Germann – a historian and an expert in the topic – recently explained to the journal Tangram. Another such example is the Institute for Anthropology at the University of Zurich, whose researchers went out to European colonies in the early 20th century – often accompanied by soldiers – to measure the body size, cranial circumference and facial angle of indigenous peoples. This was a degrading experience for those who had to be examined, according to Germann’s remarks to the news platform Swissinfo.