Feature: An evidence-based parliament

When science makes politics and vice versa

Evidence-based policymaking: fantasy, marketing slogan or reality? Its strict embodiment may not be found anywhere, but its variations are absolutely everywhere.

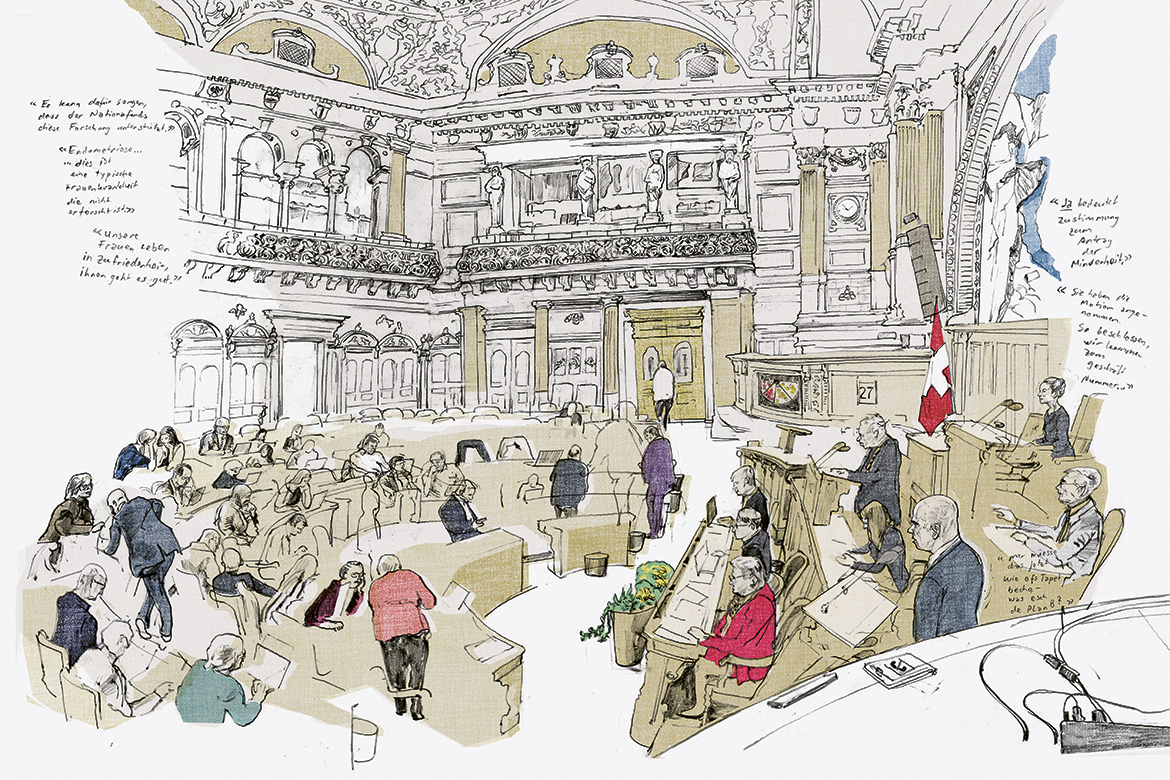

If a dossier proves contentious, it’s already too late – but scientific facts can be introduced into legislation earlier, quietly, through the backdoor. | Illustration: Christoph Fischer

Mention the nexus of politics and science and three tropes come to mind: the ivory tower, i.e., scientists produce knowledge for its own sake, divorced from society, that politicians might utilise now and then; the epistemocracy, i.e., scientists steer policy – as evoked by the attacks on the Covid-19 scientific task force, which was accused of governing Switzerland in place of the authorities; and finally, subservient science, i.e., tailor-made evidence is churned out to serve a political project for domination. This latter figure runs through conspiracy theories but is also embodied in real historical examples, e.g., the scientific racism developed to legitimise colonisation. In addition to these three mostly fantastical visions, there is actually also a fourth, more modern one: politicians deciding to base policy on scientific evidence.

The term ‘evidence-based policymaking’ was coined in the UK in the 1990s by Tony Blair’s Labour government, which popularised the concept with the slogan ‘What matters is what works’. The idea was not so much to decide on policy using the results of science; rather, it was to make policy itself scientific. “This vision, inspired by medical research, reflects a simplistic representation of how public policy is created. There is a problem, I have a hypothesis for a policy solution, I test the solution with a scientifically rigorous approach, I obtain results, and from there I can say ‘yes, this policy is good’, or ‘no, it must be improved or another one developed’”, says Melanie Paschke, a co-founder of the Science and Policy doctoral training programme, launched in 2009 by the universities of Basel and Zurich and ETH Zurich to train young scientists in interactions with politics.

In contrast to this ideal vision, one might think that elected representatives position themselves exclusively according to the ideas and interests they defend, and that they adopt or reject scientific evidence in an opportunistic manner. “This is the impression one gets if one focuses on the media moments of the decision-making process, or if one looks at politics from a purely strategic point of view”, says Céline Mavrot, an assistant professor in political science at the University of Lausanne and an expert with the Swiss Evaluation Society. By analysing the process in the field, Mavrot notes that “the interactions are more complex, and scientific evidence infuses decision-making at various stages”. In Switzerland, this transfer of knowledge takes place in government, through “highly qualified and specialised people, some of whose work is based on scientific data”, in entities at the interface between science and politics e.g., associations, think tanks and institutions mandated by the Confederation, and in the evaluation of public policies based on scientific methods and standards.

Quietly through the backdoor

The inclusion of science in the political process therefore takes place mainly “quietly, through the backdoor, in an unspectacular manner”, says Mavrot. The irruption of science can become massive in times of crisis, taking forms such as the Covid-19 task force. The exceptional nature of this task force has ambivalent effects: the evidence provided is cutting-edge, but its consideration is hampered by the fact that it circulates outside the usual procedures and established channels. In its self-assessment, the task force notes that it took six months to find a modus operandi and that the rules of communication were initially unclear. “This lack of clarity was exploited politically to assert that Switzerland had become a technocracy”, says Mavrot. The authorities contributed to this confusion by taking a back seat to the task force, which was invited to give press conferences at the Federal Palace. Mavrot continues: “Forced to take very unpopular decisions, the government pushed the scientists to the front of the stage, practising what is known in political science as ‘blame avoidance’”.

Romain Felli is familiar with both scientific research and political action, and knows both worlds from the inside, thanks to his background as a political scientist, as a former elected member of the City of Lausanne legislature and as a senior civil servant in the Department of Culture, Infrastructure and Human Resources of the Canton of Vaud. “In these areas, public policy based on scientific evidence and quasi-experimental designs is, to my knowledge, non-existent”, he says. This is due to the democratic understanding that drives Swiss politics. “There is very little willingness to replace the weighing of interests and parliamentary debates with forms of truth that are more objective but external to political circles”.

Science is not excluded from his work, however; it is regularly invited in through the backdoor: “For example, we commission research in the field of mobility”. In this way, an urban sociology study analysed the motives and times of commuter travel, showing that it does not correspond to the simple pattern of home-work journeys and rush hours. Replacing the expected image of the ‘straphanger’ with a more detailed understanding “makes it possible to think about the way in which transport provision is calibrated, with potential effects on the design of public policies”, says Felli.

Partisan politics prevails

Scientific data and standards are therefore potentially present “all the time and at all stages” in the policy cycle, says Paschke, but the expression ‘evidence-based policymaking’ does not lend itself well to describing the reality of these interactions: “Today, I would rather speak of evidence-informed policymaking”, she says, designating a process with less direct and more diffuse causalities. There are also some major limits to the possibility of including evidence in policymaking, “especially when an issue is highly polarised”, says Mavrot. The debate on the injection room for drug addicts in Lausanne illustrates this pitfall: “When the discussion started, there were PLR members open to the idea and socialists who were sceptical. Then the split between the cantonal government, which has historically been on the right and opposed to a drugs policy based on harm reduction, and the townhall, which has made the injection room a left-wing battle horse, coloured the subject in a totally partisan way, reducing the role of scientific evidence, which was nonetheless very abundant.

According to Mavrot, another obstacle is the lack of short-term benefits for elected officials. “This is clear in the case of the climate. We have had all the necessary evidence for decades, but taking it into account means making unpopular decisions, with an extremely delayed result, while the political game is focused on short-term electoral deadlines. In this field, the same scientific evidence can lead to opposite political choices, as Felli shows in his book La Grande Adaptation. Climat, capitalisme et catastrophe (The Great Adaptation: Climate, capitalism and disaster): “Faced with the reality of climate change, certain scientists, certain economic interests and certain segments of the American state apparatus have converged since the 1970s around solutions not to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but to adapt to the effects of these emissions”. In contrast to increased regulation, these adaptations went in the direction of deregulation, which corresponded to the neo-liberal political and economic agenda, says Felli.

The three experts therefore agree that science can inform and enlighten policy, but that it is not in a position to determine it, not only because it can legitimise several possible choices, but also because it is itself riddled with contradictions, establishing provisional truths on the basis of a consensus. “Consulting with other scientists and arriving at a scientific position is essential to have credibility in the political process”, says Mavrot. At the same time, “it is important to be transparent about internal disagreements, about uncertainty, about the fact that we often cannot deliver exhaustive and definitive answers”.

The honest broker in the face of wind turbines

To embody such transparency, Paschke evokes the ideal figure of the ‘honest broker’: a person or, more often, an entity (e.g., the biodiversity and genetic research forums of the Academy of Natural Sciences) gathering information and summarising it to present the advantages and disadvantages of possible choices, while at the same time adopting a self-reflexive stance that consists of stating the values and standards within which it works. We don’t get the same scientific evidence on wind turbines from the points of view of their positive contribution to energy transformation and of their negative impact on biodiversity in birds. It appears that there is a further step towards bringing science and politics into a common world, where environmental and societal emergencies are multiplying. We must recognise that all science is both a source of factual knowledge and a situated approach, and as Mavrot reminds us, that “all knowledge production depends on the way in which a question is asked and the position from which it is posed”.