RESEARCH HUB TICINO

Of supercomputers and chestnut forests: a trip to Ticino

The canton of Ticino is considered a place of longing and italianità. But beyond this cliché, Switzerland’s sunniest canton has developed into a research location with international appeal. Horizons has gone on a voyage of discovery to Switzerland’s far south.

Shock troops for the body’s defence

Halfway between the river Ticino, which lends the canton its name, and the breath-taking Castelgrande of Bellinzona, lies the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB). Affiliated to the Università della Svizzera italiana (USI), the IRB hosts more than 100 scientists from over 25 different countries involved in cutting-edge research in the life sciences.

“Our goal is to advance studies in human immunology, in particular the mechanisms of host defence”, says the IRB Director Davide Robbiani. “The immune system is that incredible weapon of the human body that recognises and neutralises viruses and bacterial threats; and not only that, it can also detect and destroy cancer cells”. Needless to say, immunology goes hand in hand with medical applications. In the past few years, for example, researchers at the IRB have launched two successful medical start-ups, Humabs BioMed and MV BioTherapeutics.

IRB’s brand-new building, inaugurated in 2021, is part of the Institute’s ambitious plan for steady growth. Since being founded in 2000 with four research groups, the Institute has attracted nine additional group leaders and plans to recruit another four in the coming years, as it expands into the fields of immunology and biomedicine. “We are about to start projects on cancer immunology with the Institute of Oncology Research, which is also in Bellinzona and affiliated to the USI. We are similarly discussing collaborations with USI faculties in Lugano and the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland (SUPSI), where there is strong research, for example, in public health and artificial intelligence”, Robbiani adds.

Even outside the IRB, Robbiani is enthusiastic about the scientific landscape in Ticino. “There is considerable momentum and enthusiasm for the life sciences in Ticino at the moment, and this has led to the development of an innovative medical study programme at USI together with its partner university, ETH Zurich”, says Robbiani. Within this dynamic environment, IRB is contributing to Ticino’s aim of promoting growth in the life-sciences sector. “The canton also seems to have become a magnet for life-science entrepreneurs: Two new start-ups were launched in Bellinzona in the last few months, and a third will join them soon”.

In 2020, Robbiani moved his immunology lab from New York to Ticino, his homeland, to assume the directorship of the IRB. When asked about his own scientific goals, he replies pragmatically: “One scientific question I’ve been thinking about quite a bit recently is immune memory. Like our brain, the immune system has this capacity to remember past encounters. Understanding the molecular basis for long-term immunological memory is a challenge I find both important and fascinating”.

Using data to fight forest fires

Stunning forests, delightful vineyards and plenty of sun. This is the Ticino we all know and enjoy, but such a rich landscape needs care. This is the aim of the research group in Cadenazzo led by Marco Conedera of the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL), which develops scientific tools to monitor and manage natural systems in the Southern Alps.

Of the five WSL sites across the country, Cadenazzo is the only one located in the Southern Alps. Conedera’s team of four aims to understand how and why the southern landscape of wild forests and cultivated lands is changing. “On one side there is global warming, and on the other, we have drastically altered how we use our land since World War II. Both factors strongly influence the way the landscape is changing”, Conedera says. One of the main consequences of rising temperatures and a lack of management in mountain agriculture has been the spread of forest fires. For this reason, when Conedera got his degree in forest engineering from ETH Zurich in 1984 and returned to his hometown of Arbedo in Ticino, he felt the need to study his land and the fires afflicting its chestnut forests. Ultimately, this choice led him and his colleagues to develop fire prevention tools such as FireNiche, software that uses historical weather and fire data to calculate the risk of forest fires. FireNiche is now used in Ticino to send out public alerts or fire bans when needed. “Forests affect city dwellers, too”, Marco Conedera notes. “For example, in December 2023, it will be 50 years since the terrible forest fire in Val Colla that obscured the sky above Lugano for three days”.

But fire is not the only problem. Global warming, the absence of natural barriers between Switzerland and the Mediterranean countries and a population that is always on the move together foster the proliferation of new species in southern Switzerland. Palms are the most glaring example. Newly introduced species must be studied thoroughly to learn their impact on the ecosystem, the soil and humans. For example, new species may bring new spores, and new spores can cause new, often severe, allergic reactions.

Remarkably, research carried out at the WSL site in Cadenazzo is making it possible to predict what will happen to northern Switzerland’s landscapes in the decades to come. “As temperatures keep rising, what we see now in Ticino will happen in 30 years’ time in the rest of the country. We are already experiencing this”, says Conedera. “In the lowlands of northern Switzerland, some tree species, such as ashes and spruces, are increasingly suffering. Many people are considering replacing them with species from the South, such as the chestnut tree. Switzerland has a unique opportunity to face the consequences of global warming thanks to experience from the South”.

Pioneers of artificial intelligence

“Build an artificial intelligence smarter than yourself and then retire”. This has been the ambitious goal of Jürgen Schmidhuber since his teens. Now, after more than three decades of research at TU Munich and the Dalle Molle Institute for Artificial Intelligence Research (IDSIA), the computer scientist whom the media have called the “father of modern AI” may have almost achieved his objective and, in the process, led his group to milestone discoveries in artificial intelligence.

IDSIA is part of both SUPSI and the USI and it began to lead research into artificial intelligence soon after its founding in 1988 by the visionary Italian philanthropist Angelo Dalle Molle. He dreamed of a world in which humans and technology lived side by side, striving towards a better quality of life. Since 1991, Schmidhuber’s lab has been conducting pioneering research into the algorithms underlying neural networks, which are commonly used in the field of artificial intelligence.

The basic concept of a neural network is indeed closely related to how humans think and learn: “Our brain has billions of neurons: Some are input neurons that feed the rest with data like sound, vision, tactile information, pain, hunger, etc. Others are output neurons that move muscles”, Schmidhuber says. “Most are hidden in between, where thinking takes place. The neural network learns by changing the strength of connections that determine how strongly neurons influence each other, and which seem to encode an entire lifetime of experience”. According to Schmidhuber, the same is true of their artificial neural networks, which learn to recognise speech, handwriting or video, minimise pain, maximise pleasure, drive cars and much more.

The algorithms developed by his lab are currently employed by the majority of well-known information technology giants, e.g., Google, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft. In 2014, Schmidhuber translated his theoretical discoveries into the company NNAISENSE, which is based in Lugano and delivers cutting-edge AI solutions for industry and finance. Schmidhuber is very optimistic about the future of this industry in the heart of Europe: “When we founded our company, NNAISENSE, almost all the investors who called us were located outside Europe, on the Pacific Rim”. But he adds: “That’s no longer the case. In our second round of funding, we suddenly received lots of interest and substantial investment from European businesses too. Generally speaking, we can see just a reflection of the tip of the iceberg that is coming our way”.

Therapeutic molecules from a 3D printer

Accurate and timely medication delivery: This is the mission of InkVivo, a start-up based in Lugano with labs in Zurich. Elia Guzzi, its co-founder together with Stefano Cerutti, here talks about the ambition that fuels his work.

“At InkVivo, we manufacture special drug delivery systems that ensure the controlled release of active ingredients. Basically, we incorporate therapeutic molecules into our bio-ink. We then use a 3D printer to ‘print’ medication that can either be implanted in the body or ingested. The original idea was to develop a system for postoperative care that would release small molecules to control inflammation and pain after orthopaedic surgery. Later, we realised that we could also leverage our biomaterial for other clinical challenges, like tissue regeneration, cancer chemotherapy or the targeted delivery of micronutrients.

“The scientific idea is based on my PhD research at ETH Zurich. In mid-2020 I thought: How can we translate my research into a medical product? As I started interviewing experts in the field, I realised that being able to deliver drugs in a controlled way was something that the field of medicine really needed. Unlike existing solutions, our method doesn’t focus solely on the chemical formulation, but also on making the delivery system. We are rather unique in that regard.

“Before starting my PhD, I worked in a start-up and really enjoyed that environment because it’s very dynamic. Every day you get to do something different. Yes, it’s a lot of work and responsibility, but you are very valued. It’s really sensational. I felt free to home in on my interests and then use my technical skills to solve problems. I think this is what is most important to me: seeing a challenge and addressing it with my own ideas.

“Back in 2020, my business partner Stefano Cerutti was doing his MBA. We have been friends for almost ten years, and I knew he was interested in innovative technologies as he’s also an engineer by training. So I reached out to him and asked: “Do you think we can create a start-up right away with my bio-ink?”, and he promptly replied, “Elia, you need to think about the business side of things – it’s not just about the technology!”. From that point on, we started working side by side, and he took over the financial part. For me, as a scientist, it’s important to have support with the business.

“In 2022, we won the Boldbrain Startup Challenge organised by Fondazione Agire and USI. The condition was that we would incorporate our company in Ticino, and we seized the opportunity. I am from Ticino myself, and I think it’s an honour to bring something back to where I grew up. We are now located in the USI Startup Centre, an incubator where we can plan our next steps with experts. When we need support, they put us in contact with coaches or experienced people. For example, we are getting help on our business strategy and collaboration agreements. This is extremely valuable, since we have to deal with big players”.

The green energy of the future

The future is green, and Ticino does not intend to be left behind. Alberto Ortona, a group leader at the Hybrid Materials Laboratory at SUPSI in Lugano, is answering the call for sustainable energy with a wide range of innovative technologies.

“If you check the number of European projects founded in Switzerland every year, you will see that Ticino is probably one of the most active areas. There is a reason for this: we are conducting a lot of research and we are doing it well, especially considering our population size of just 350,000 people in the entire canton. I am in a very narrow field, but I would say that we have experienced something of a boom in the last few years.

“To date, we are mainly designing, testing and making what we call complex ceramic structures for different purposes. For example, we’re working on high-tech applications dealing with energy in the form of so-called concentrated solar thermal energy, in which many mirrors concentrate sunlight in one spot. When the heat from all those mirrors converges there, it heats up a component that then transfers all the energy into a fluid.

“We are also participating in a European project called Hydrosol Beyond, developing systems to recover heat after ‘water splitting’, a process used to extract pure hydrogen and oxygen from water. Our goal is to recover the heat generated during this process and to use it to pre-heat the water-splitting instrument, thereby recuperating energy. For this, we are creating a new generation of heat exchangers that have to work at very high temperatures, around 1,200 degrees Celsius. They also have to be very compact, which is why we need ceramic architecture.

A third example is another national project that has meanwhile become a European project: thermochemical heat storage. By absorbing and releasing water from a chemical solution with sodium hydroxide, we can store heat in summer and then release it in winter. As you can see, none of these technologies involves the use of fossil fuels. Our applications are mostly for the production, transfer and storage of sustainable energy.

“I just ‘lost’ two very nice guys who were working with me, but I’m very happy for them. They have moved to two companies in Ticino, and are pretty much doing what they were doing here in their research at SUPSI. This is also another sign that local companies are hiring people who are highly specialised in materials science.

“I don’t talk about achievements; I prefer to talk about dreams. My dream would be to make a component for a machine that has 100-percent efficiency. But of course, this is just a dream. It’s a big dream, it’s an impossible dream, but it’s my dream”.

An alpine supercomputer

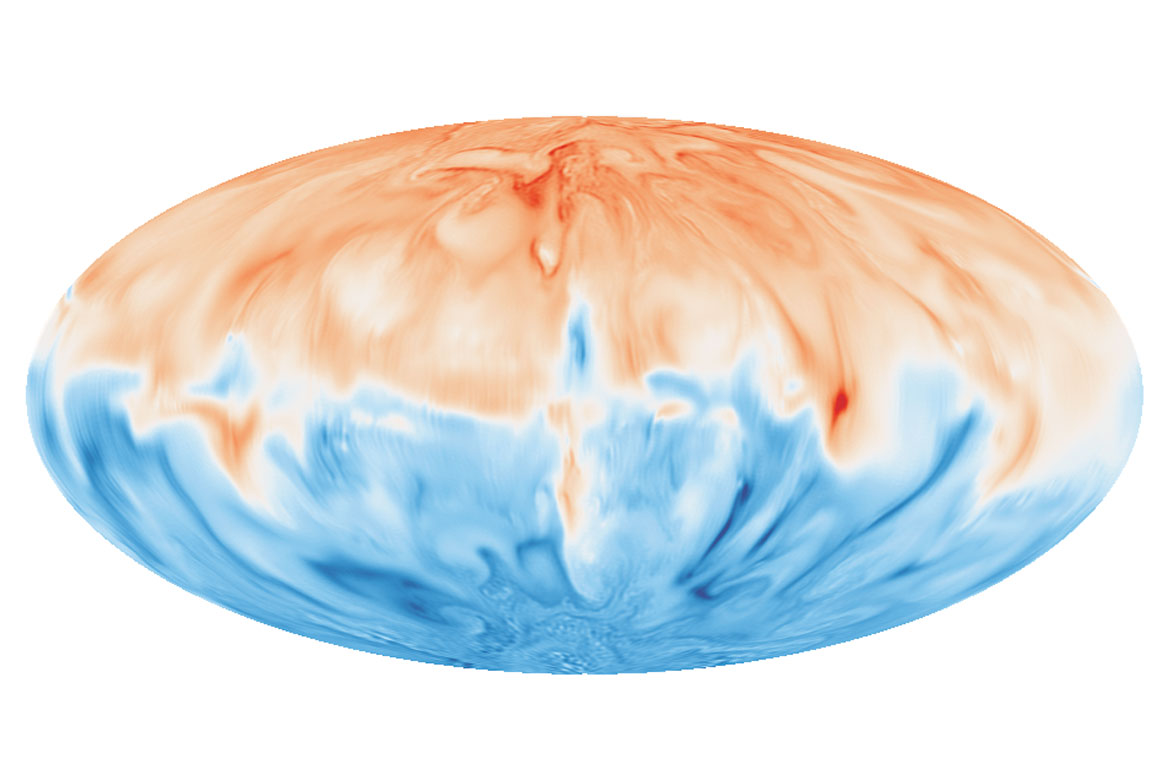

The computational heart of Switzerland beats in Lugano, the home of the Centro Svizzero di Calcolo Scientifico (Swiss National Supercomputing Center, CSCS), which belongs to ETH Zurich. It provides top-notch infrastructure for data management and high-performance computing to scientists in Switzerland who need significant resources for simulations and computational calculus. Maria Grazia Giuffreda here discusses the past and future of computational science in Ticino and Switzerland. She has served as an associate director of the CSCS since 2013.

In 2023, the CSCS will have a new world record-breaking supercomputer, called Alps. Why did you choose this name?

We always name our supercomputers after Swiss mountains. In this case, the name ‘Alps’ reflects a new idea of computational infrastructure where a single machine will enable you to create virtual clusters, like several individual peaks in the Alps. Alps will run calculations in many fields of research, e.g., the weather and climate, materials science, life sciences, nuclear fusion and astrophysics. This new system is going to be the most powerful AI-capable machine in the world, and CSCS is already in contact with IDSIA (see the section on Jürgen Schmidhuber above – Ed.) to find out what is needed to use this new infrastructure to its full potential.

Why is the CSCS located in Ticino?

This was ultimately a political decision. Back in the 1980s, when politicians and scientists started discussing a supercomputing centre in Switzerland, Ticino was able to make the best offer to build a centre in the given time. Being physically detached from ETH reinforces the fact that our mandate is to serve all of Switzerland. We treat all Swiss scientists equally, with no preferential treatment for anyone. I have to say that the new Gotthard and Ceneri Base Tunnels have really brought us physically closer to the rest of Switzerland. Since the tunnels opened, we have been getting many more visitors and users from the other side of the Alps who want to talk to us. We are also contributing to the cantonal economy, hiring technicians from Ticino and creating a lot of job opportunities for local people.

Is Ticino a good environment for science?

Since I moved here 16 years ago, Ticino has discovered its potential for technology and science. It has experienced an enormous revolution, particularly in computing and artificial intelligence. These days, interest in AI and machine learning is so high that Ticino could easily become the Silicon Valley of Switzerland. Despite its size, Ticino has a large concentration of strong, innovative institutes in several fields, and we should be making use of this.

Computational sciences are often dominated by men. How do you feel about this?

The problem is that STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) are still very male-oriented, also here in Switzerland. Even now, as associate director, I still have to keep proving that I’m in the right place doing the right thing. You are always under scrutiny. As women, we must be more self-confident. Sometimes I get the feeling that we don’t even start things because they’re too difficult. We give up without even trying, and that’s not the right attitude.

Simone Pengue is a freelance journalist in Basel and Lugano. Illustrations by Clara San Millán