Humour

Gender is no laughing matter

On average, men produce better punchlines than women. And women executives who tell jokes are regarded as lacking in competence. When it comes to humour, gender can play a big role.

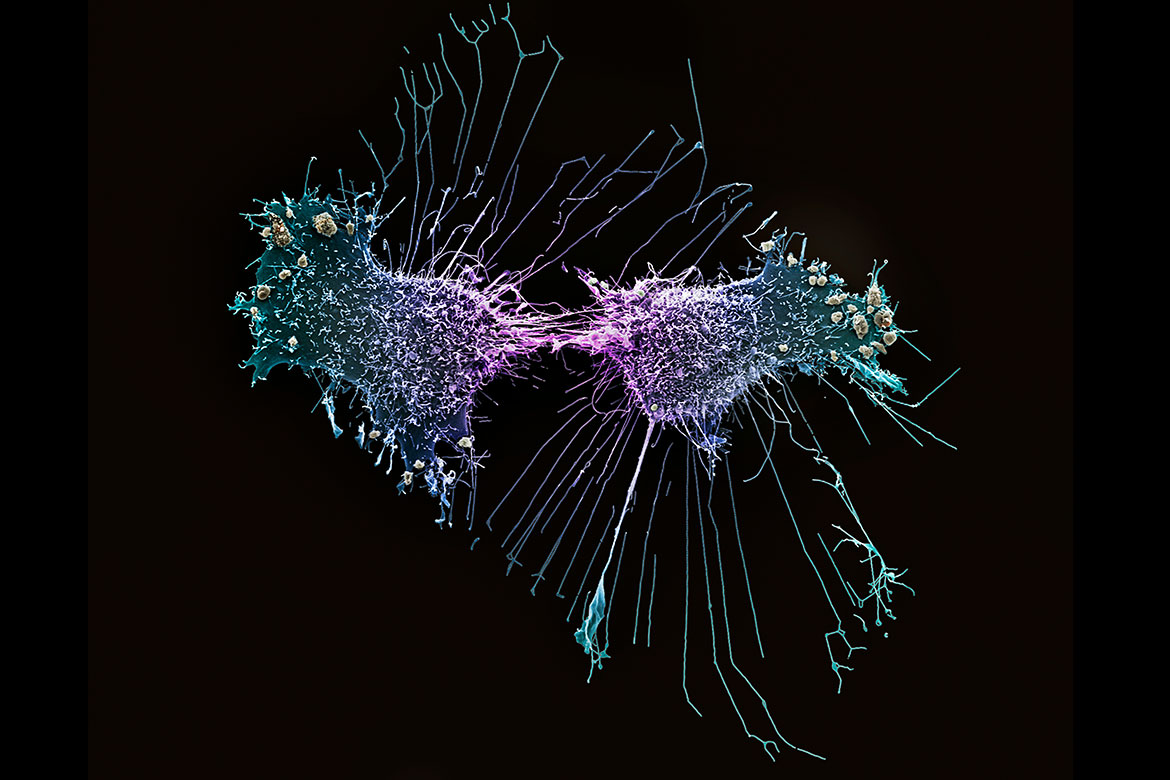

It seems straightforward: Women like funny men, so men try to be funny. But does it always work? | Image: Dan Cermak

If you think of a person you regard as particularly funny, who comes to mind first: a man or a woman? In a meta-analysis conducted in 2019, the Israeli anthropologist Gil Greengross and the American psychologist Geoffrey Miller examined 28 studies with a total of more than 5,000 participants. They concluded that, on average, men have a slightly more pronounced “humour production ability”. Most of the research studies they analysed had followed a similar pattern. The men and women who were participating had to fill out speech bubbles in cartoons or add funny captions to pictures. The results were then evaluated by a mixed-gender jury and sorted according to their degree of ‘funniness’, without the members of the jury knowing whether the jokes were made by a man or a woman. The men won.

Self-irony’s important

Willibald Ruch is a professor of psychology at the University of Zurich, where he heads the personality and assessment section. He has been researching into humour for over 40 years, and offers a different perspective on the findings of Greengross & Co.: “Humour encompasses much more than just making jokes and punchlines. Self-irony and situational comedy are also important, for example. Plus a basic ability to cope well with the adversities of life, and to laugh about yourself and your own misfortunes. It’s not gender that plays the decisive role in this, it’s your personality”.

Ruch’s team reviewed and evaluated the entire peer-reviewed scholarly literature published on humour and gender difference from 1977 to 2018. They found that hardly any differences exist in how we understand humour, or in our preferences for certain types of it. Differences primarily exist in the production of aggressive humour, such as cynicism and sarcasm, and to a lesser extent in the context-free creation of jokes and punchlines. As in the case of Greengross and Miller, Ruch’s team found that men not only scored better, but also invested more in the presentation and performance of humour.

Gender roles have an impact

The evaluation undertaken by Ruch’s team also showed that women value men’s ability to produce humour far more than they value men’s receptivity to it; for men the exact opposite applies. These preferences correspond to the stereotype of the funny man and the laughing woman, and could in fact be acting as a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is suggested, for example, by the large-scale studies carried out by the American behavioural psychologist Paul McGhee in the 1970s. He investigated how the humour of boys and girls develops in different directions between their time in kindergarten and when they begin school; the boys were the active jokers, while the girls giggled at them.

McGhee believed his findings confirmed that both sexes increasingly felt the demands of gender roles from kindergarten onwards, the boys having more success with their jokes than the girls with theirs. As a result, the boys continued to develop their talent, trying out new, more incisive styles of humour that were also often correspondingly more aggressive. However, recent studies – e.g., one conducted by the German psychologist Marion Bönsch-Kauke – suggest that gender-specific differences among children are less pronounced today.

Greengross and Miller, by contrast, explain these gender differences with the theory of evolution, according to which women control sex, and men have to do everything to stand out and present their ‘good genes’. But this reasoning is controversial. The same theory claims that humour ought to indicate character traits such as intelligence and creativity – a link that is supported by earlier research on the part of Miller and Greengross. In a study of 400 students, they were able to show that intelligence – by which they mean the artful use of language – is linked to the ability to produce jokes such as funny cartoon punchlines.

Self-confident or insecure?

This biological, evolutionary interpretation is also important in the work of Pascal Vrticka, a neurobiologist from Lucerne. It shows that when we laugh at a joke or a funny situation, we follow a two-step process. Certain brain regions responsible for logical thinking first perceive a discrepancy; once this is resolved, the centres in the brain for rewards and emotions spring into action. In other words, jokes trigger feelings of pleasure. Together with a team from Stanford University, Vrticka discovered that the emotional centres in the brains of girls are activated far more strongly during funny scenes in a film than is the case with boys, whose brains react more strongly to the course of the story. This observation is consistent with earlier discoveries by the same research team in their studies of both women and men. Vrticka suspects that women’s brains might have become specialised in evaluating humour, while men’s brains might be more oriented towards producing it. This is all probably related to processes of sexual selection.

Ruch’s evaluation of the literature also found differences in the use of humour, especially at the workplace. Women in positions of leadership, for example, are on average rather more business-like than their male colleagues when it comes to humour. The reason is not difficult to grasp. A recent study by the University of Arizona, for example, involved a number of study participants watching videos of women executives giving a presentation. Those women who made the occasional humorous remark during their presentation were assessed by the participants (both women and men) to be less competent and less possessed of leadership qualities than ‘humourless’ women.

But when men in leadership positions tell the same jokes, they gain prestige and authority. The reason for this, say the authors of the Arizona study, might lie in existing prejudices. Men are still generally considered to be more competent in professional matters and have a kind of competitive edge in matters of credibility. This, the authors believe, is in turn reflected in how their humour is interpreted. In men, humour is read as a sign of self-confidence; in women, however, it is often regarded as an expression of insecurity.

Humour can signify toxic masculinity

In some cases, however, humour can also be detrimental to men. Jamie Gloor is an assistant professor of business administration at the University of St. Gallen. Together with an international team of researchers, he wanted to find out whether positive humour can help to break down the barriers and fears between the sexes that have become increasingly prevalent in the workplace since the #MeToo era began, and that can reduce the career opportunities of talented women because of men who fear accusations of inappropriate behaviour. Gloor and his team had job candidates insert a ready-made, harmless joke into their job application videos, and then had those videos rated by 1,189 HR officers.

They found that positive humour can indeed open doors, for both women and men. But in companies that had a history of problems with sexual harassment, the men telling the joke were judged negatively by female HR managers. “Their quips conveyed the impression that these men were potentially toxic”, says Gloor. This is because sexual harassment is often committed through ‘jokes’. Whether or not #MeToo will lead to a fundamental reassessment of male humour and alter men’s behaviour remains open to question.