Feature: The limits of brain research

The deep chasm between inside and out

How do physical processes in our brain result in our subjective experience? There is no agreement about whether we will ever be able to solve this major problem in consciousness research. In the meantime, researchers have enough other detailed questions that need to be answered.

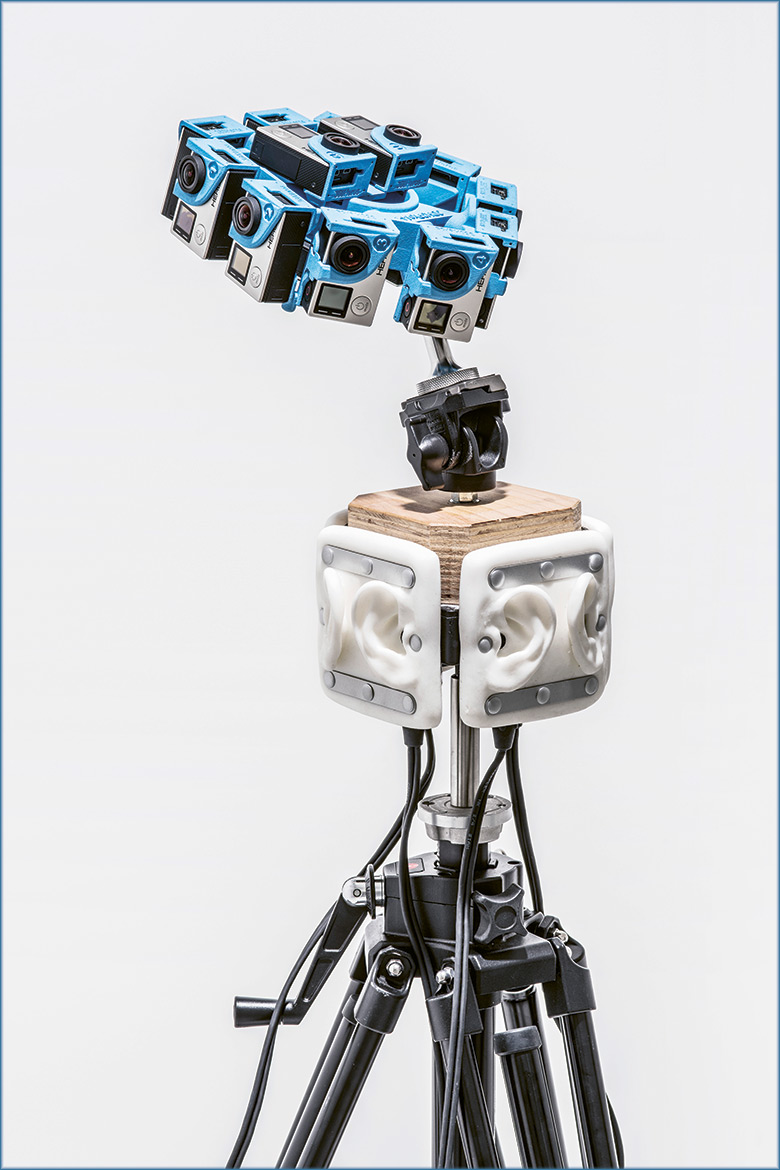

This apparatus provides all-round photography and realistic audio recordings. A team led by the neuroscientist Olaf Blanke is using it to study how we navigate in virtual reality. | Image: Matthieu Gafsou

1 – What is consciousness?

To this day, we still haven’t managed to formulate any clear definition of this concept. The British neuroscientist Anil Seth is the co-director of the Centre for Consciousness Science at the University of Sussex and he has been studying consciousness for over two decades. But the lack of a definition isn’t giving him any headaches. In his book ‘Being you’, he defines consciousness quite simply as “any kind of subjective experience whatsoever”.

He admits that this might sound a bit too simple, even trivial, but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing: “For as long as we only have an incomplete understanding of complex phenomena, then giving too precise a definition can hem us in or even lead us astray”.

2 – Where is it?

In his book on the history of brain research, the retired Austrian professor of philosophy Erhard Oeser relates how the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that the brain was nothing more than a cooling unit that served to lower the temperature of the blood when it was loaded with nutrition. This, he believed, helped human beings to fall asleep.

Aristotle was also convinced that the human soul was situated in the heart, though with one important exception: he distinguished between three different types of soul, of which only two were to be found in the heart: the anima vegetativa and the anima sensitiva, the souls of bodily functions and of perception respectively. The spirit, however – the actual site of our ideas and the repository of reason, was not at home in the body, thus neither in the heart nor the brain, which is why it was immortal.

In the 17th century, the French philosopher René Descartes was the first person to formulate a concrete idea of how of body and soul interacted, and he situated our consciousness quite clearly in the brain. Everything around us might be an illusion, he wrote – a dream or the trickery of a demon – and we may doubt all acts of perception. But one thing ultimately remained: Descartes himself, who was thinking about all of this. He summed up his reflections in a sentence that we can today find in all manner of variations, even printed on pyjamas and coffee mugs: “I think, therefore I am”.

Descartes declared that while the physical body comprises matter that moves and expands mechanically in space, the thinking self was made up of a fundamentally different substance. In a comprehensive introduction to consciousness, the British psychologist and author Susan Blackmore writes how Descartes believed that in the brain (or, more precisely, in the pineal gland), corporeal matter, the res extensa, interacted with thinking matter, the res cogitans. This Cartesian dualism of two separate substances – the notion that our consciousness neither arises through physiological processes in the brain nor is in any way connected to them – has few adherents today, however.

“No one denies that the brain is relevant to consciousness”, writes Blackmore. “They just disagree fundamentally about its role”. According to Seth, one of the major debates currently taking place is about the distinction coined by the philosopher Ned Block between so-called access consciousness and phenomenal consciousness.

In a Zoom conversation, Seth explained that access consciousness is the state in which it is possible for us to control our behaviour, direct our attention or make reports; from this perspective, it is primarily the frontal brain regions that are crucial to consciousness. But research into phenomenal consciousness is more likely to involve activity in the posterior parts of the brain, he says, because this is where people’s perceptions and the content of those perceptions are focused. Disentangling the two interpretations of consciousness, however, is far from easy, he admits. “Maybe both sides are right”.

3 – What are the ‘hard’ problems of consciousness?

To begin with, of course, even the easy problems of consciousness research are anything but easy to solve. When the Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist David Chalmers proposed a division between the ‘easy’ and ‘hard’ problems of consciousness in the 1990s, he merely wanted to make it clear that the former are likely to be solvable, in principle, by standard scientific methods, because what is at issue there is the role of consciousness in relation to sleep and wakefulness, our degree of attention, or controlling our behaviour (as Blackmore also writes).

It’s the hard problems, however, that are the really tricky ones: How do physical processes in the brain ever become subjective experiences in the first place? Why is seeing red not the same experience as seeing blue? Why does it feel different to miss someone than to smell fresh coffee, or to listen to the singer Helene Fischer? As the British philosopher Colin McGinn once put it: “How can technicolour phenomenology arise from soggy grey matter?”

4 – Can the hard problems be solved at all?

Is there an answer to this question of all questions about consciousness? ‘Yes’, some say, though as Blackmore writes, the solution will require a completely new understanding of the nature of the Universe and physical principles that remain as-yet unknown. Others, however, are convinced that the answer is ‘no’, including McGinn, who is a ‘mysterian’ – in other words, he thinks that human beings simply lack the kind of intelligence that would be needed to grasp in full the essence of consciousness. Just as a dog will never succeed in reading a newspaper or appreciating poetry, no matter how hard it might try.

Steven Pinker is a psycholinguist and cognitive scientist. He is similarly pessimistic, although Blackmore claims that Pinker concedes the possibility that a “Darwin or Einstein of consciousness” might yet be born into the world who will one day surprise us all with spectacular insights. Illusionists like the American philosopher Daniel Dennett are even willing to claim that the ‘hard problem’ does not exist at all – indeed, he believes that subjective experience is a figment of our imagination. The crucial question is therefore: How does it come about that we are susceptible to such an illusion in the first place?

Researchers like Seth, who are close to physicalism, take a more pragmatic approach to the big question of consciousness: “One may simply take an agnostic attitude to it”, he says. He describes physicalism as the idea that everything in the Universe is physical in nature, hence consciousness, too, must have a physical basis and originate from a specific ordering of physical elements. Seth’s intention is to get to the bottom of the simple problems with all the more vigour. “Of course, I can’t guarantee that exploring the physical underpinnings is sufficient to explain consciousness”, he admits. “But it is certainly the most productive thing we can do in the meantime”.

And perhaps the hard problem may one day also be solved in this way – or will at least eventually lose the aura of mystery that has surrounded it for so long. Seth reminds us here of the hunt for the mysterious élan vital that continued even into the 20th century. We still have no all-encompassing theory of life, he writes. But our understanding of the numerous sub-processes that make up life has long since made the search for a general ‘theory of life’ obsolete. “Making progress in science does not always mean finding answers to the initial questions”, he insists. “It is also a sign of progress that the questions change”.

5 – How is consciousness being researched today?

According to Seth, the approach usually adopted in consciousness research today involves accepting subjective experience as fact, but without declaring it to be one’s direct research goal. Instead, people first grapple with the easy problems. Although it remains an interdisciplinary field in which psychology and medicine play important roles, the neurosciences have today replaced philosophy as the most important discipline in it.

Since the 1990s, the principal approach has been to search for the so-called ‘neural correlates of consciousness’, or NCC. This term was coined by the British physicist and molecular biologist Francis Crick together with the neuroscientist Christof Koch: “These are the smallest set of brain mechanisms and events sufficient for some specific conscious feeling, as elemental as the colour red or as complex as the sensual, mysterious, and primeval sensation evoked when looking at the jungle scene on the book jacket”.

Crick was a Nobel Laureate who had helped decode the structure of DNA in the 1950s. According to Seth, the fact that such a figure was one of the first to begin searching for these correlates made a decisive contribution to re-establishing consciousness as a respectable field of research. It had fallen completely out of favour for much of the 20th century, when psychology restricted itself to the study of behaviours that could be observed from the outside.

In the past decades, the search for the NCC has undoubtedly produced more concrete results than any other research approach. But it is slowly reaching its limits. The main problem, says Seth, is this: “Correlations are not yet explanations”.

Recent years have produced a veritable flood of theories of consciousness. But they have not made the topic itself more easily understandable. It is often not even clear what kind of understanding of consciousness underlies the various theories, nor what exactly they are trying to explain. Some cannot even be tested. As an example, Seth mentions ‘panpsychism’, which holds that some manner of consciousness is inherent in every form of matter. “Even if this theory were true, how would we ever prove it?”, asks Seth. In his opinion, such assertions are not very fruitful, and he also considers mysterianism to be a rather fainthearted affair.

For Seth, the great challenges of consciousness research involve formulating the various theories more precisely so that they can be tested and compared with each other. And perhaps a few of the most promising explanations will eventually stand out from all the noise around them.