IN BRIEF

Genome editing in hospitals

As early as this year, the United States Food and Drug Administration could approve a genetic treatment for the inherited blood disorder sickle cell disease.

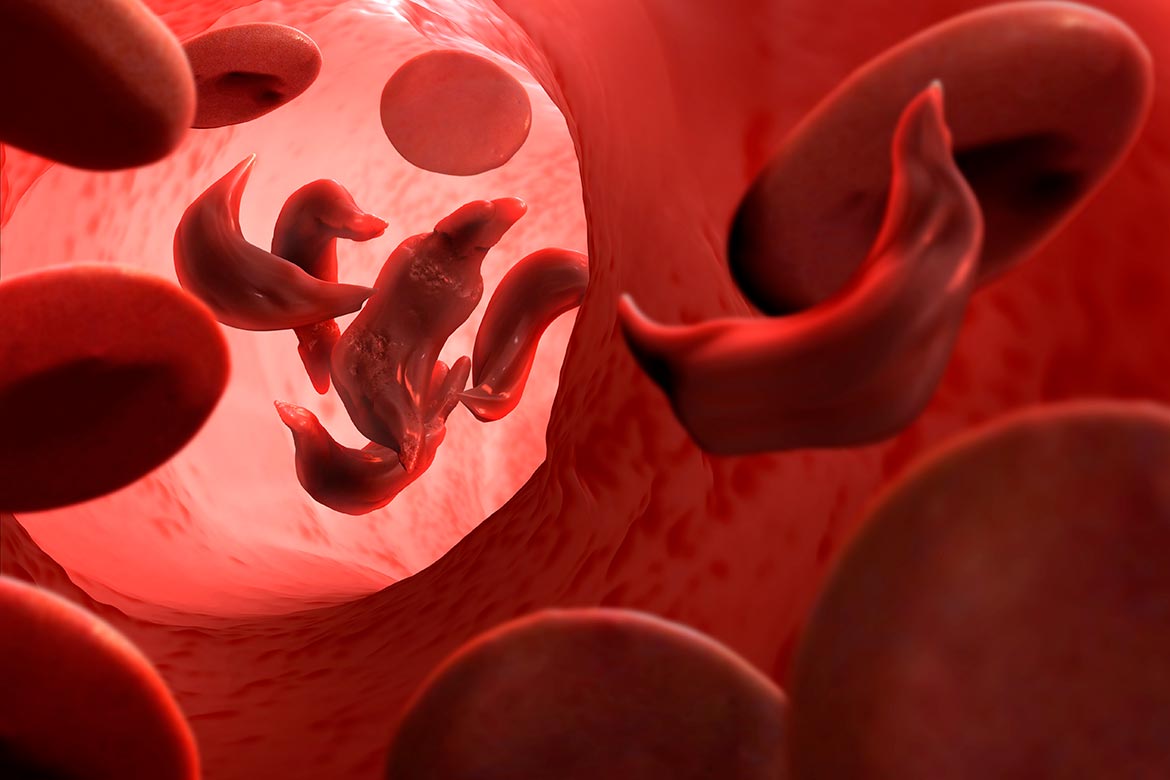

A gene variant can cause red blood cells to take on a sickle shape, making them less flexible and more fragile. This is why they can clog fine blood vessels and obstruct the oxygen supply to our tissue. | Image: Science Photo Library / Keystone

CRISPR-Cas is a method for modifying the genetic material of cells both simply and precisely, and was first described in print in 2012. It won Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna the Nobel Prize in Chemistry – but by then, it had already been used successfully to treat a person with a hereditary disorder: Sickle cell disease. Victoria Gray from Mississippi suffered from this genetic defect that deforms the shape of red blood cells. As a result, her blood was no longer able to flow properly. This type of anaemia can lead to severe pain, organ damage and an early death. But thanks to so-called genome editing, she is still doing well today.

Gray is not alone. The Financial Times quotes Robin Lovell-Badge, a developmental biologist at the Francis Crick Institute in London, as estimating the current number of patients treated successfully at around 70. David Liu of the Broad Institute in Cambridge MA believes that the number lies at over 200, according to the MIT Technology Review. At present, countless clinical trials are underway for treating diseases such as cancer, genetic blindness, diabetes and HIV/AIDS. There is a general sense of optimism, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is widely expected to approve this therapy for sickle cell disease in the current year. The focus is now shifting to how these expensive interventions can be made accessible to as many people as possible.

The situation is very different, however, in cases of inheritable modifications of germline cells. In 2018, Jiankui He, a biophysicist at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, declared having used genome editing to create HIV resistance in three new-born babies. The research community condemned this intervention as irresponsible, and He was sentenced to three years in prison in China. In March 2023, the organising committee of the Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing similarly declared itself in opposition to such a procedure, because the safety of the patients was not guaranteed, nor were the necessary societal and regulatory conditions in place. However, the Summit itself was adamant that research with embryos remains important, declaring that “[b]asic research in this area ought to be continued”.