BIRTH TRAUMA

Birth trauma is real

Giving birth is a natural process, but that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily something wonderful. We look at how birth trauma occurs, how it expresses itself, and what can be done about it.

Flashbacks, nightmares and excessive worrying about one’s child: birth-related post-traumatic stress disorder has a lasting impact on both parents and their kids. | Image: Eylul Aslan / Connected Archives

It is often still taboo to talk about the difficult or painful aspects of childbirth, or about when it fails to meet social expectations. Whether miscarriages, difficulties with breastfeeding or postpartum depression: “All these topics are often bound up with feelings of great shame and isolation”, says Antje Horsch, a clinical psychologist and professor at the University of Lausanne. She wants to help change this through her exhibition “Bébé en tête/Baby in your head” (see box).

Caroline Chautems is a social anthropologist who is busy with postdoc research at the Centre for Gender Studies at the University of Lausanne. She believes that this stigma is also strongly linked to the individualisation of responsibility such as is characteristic of wealthy countries like Switzerland. If something doesn’t work as expected, then you are supposed to focus on your own resources, she says: “Resilience is contextualised here as a very important virtue”. In Switzerland in particular, she believes, the family is also seen as a private matter.

According to Chautems, the pressure felt by parents has also increased since the rise of so-called intensive parenting in the 1990s. “Parents no longer simply raise their children. They’re constantly occupied with optimising their development”. This is especially true of breastfeeding during infancy. Health professionals have issued so many recommendations about the benefits of breastfeeding, says Chautems, that it puts a lot of pressure on parents.

Anyone with access to so much information is expected to use it in the best possible way. So if you can’t breastfeed, or don’t want to, this can lead to a sense that you’ve failed or that others are judging you. What’s more, she says: “Since the introduction of the pill in the 1960s, having children has been seen as exercising your free choice”. Today, pregnancy is upheld as a rare, precious experience that you choose quite consciously. As a result, says Chautems, there is increasing pressure for your pregnancy to proceed in line with society’s supposed expectations of it.

But at the same time, she says, more and more initiatives have been emerging in recent years that encourage women to share their difficult experiences with others – whether it’s violence in the delivery room or the loss of a baby – and to talk more openly in general about the postpartum period. The #MeToo movement undoubtedly also paved the way for this.

A medically smooth birth can still be traumatic

“Giving birth is a natural process for which our body is provided with the necessary equipment”, says Horsch. “But this doesn’t mean it’s bound to be a wonderful experience”. Her research is focusing primarily on traumatic births: “These can have long-term, serious consequences for the mother, the child and the co-parent”. A survey has confirmed that roughly a third of all women who have given birth regard the experience as having been traumatic. “What’s decisive”, says Horsch, “is how the process is experienced subjectively. A birth can proceed smoothly from a medical point of view and still be traumatic for the mother”.

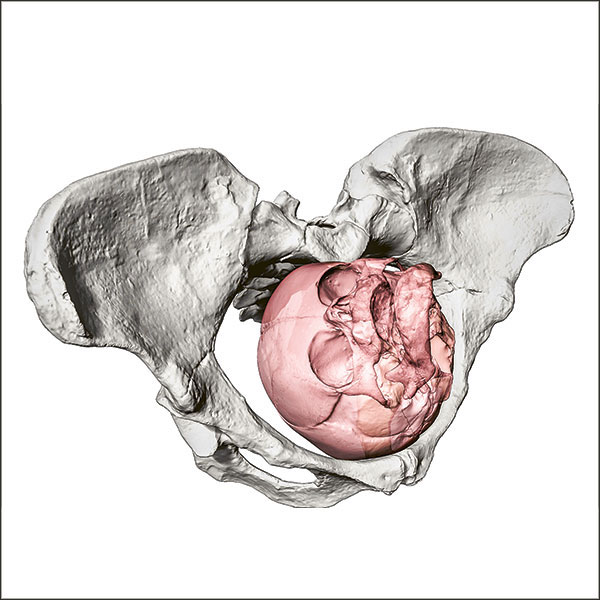

Roughly four percent of all women giving birth develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This risk increases significantly after an emergency caesarean delivery, a premature birth or the loss of a child – in such cases, 15 to 20 percent of women are affected. Childbirth-related PTSD isn’t the same as postpartum depression, even though both are accompanied by symptoms such as constant low spirits and negative thoughts. PTSD can also include flashbacks or nightmares, and can lead to the person affected avoiding conversations and situations that remind them of the birth – even including check-ups with the doctor. Those affected are often excessively vigilant and constantly worried about their child.

The notion that trauma could occur from something with positive connotations, like a birth, was initially met with great resistance among researchers, explains Susan Ayers. She’s a psychologist at the City University of London and has been researching into this topic since the 1990s. Today, however, there is an increasing awareness and acceptance of it in specialist circles. “It’s only the public perception of it that is still lagging somewhat behind”, she says. In the UK, too, people still often react with a lack of understanding towards women who have been traumatised by childbirth. Difficulties that they might experience during the so-called perinatal phase are similarly taboo there. “But you’ve got a healthy baby” is what those affected are constantly being told. “And yet that’s not enough”, says Ayers. “The mother ought to be doing well too”.

Outdated antenatal care

Birth trauma can also be transferred to the newborn child through its interactions with its mother. Horsch and her team have shown that women with suspected birth trauma experience stronger reactions to stressful situations shortly after giving birth than is the case with other mothers. They differ not just in their behaviour, but also in terms of physiological reactions such as their heart rate and cortisol levels. Changes like this, Horsch believes, could have a negative impact on a mother’s early bonding with her child. Parents normally provide the framework by which babies learn to regulate their emotions. But if they themselves are overwhelmed by strong emotions, it can be difficult for them to instil this competence in their child.

The children of traumatised mothers are also more likely to endure sleep disorders at the age of two, according to a cohort study led by Horsch. What’s more, women who are affected are less likely to want another child. If they do, then they only take this decision several years later. “But if the antenatal phase proceeds in a positive fashion, many mothers also experience it as a healing process”.

It is essential to ensure good communication between expectant parents and healthcare professionals if a traumatic birth is to be avoided. Horsch knows that this already starts with antenatal classes, though many couples find them outdated because of their excess emphasis on childbirth as a natural process. They tend not to provide adequate preparation for possible complications and the medical interventions that can become necessary in hospital.

Maintaining dialogue during the actual birth is also vital. Horsch is insistent that the specialist staff have to be made more aware of the need to communicate actively with the parents-to-be. Traumatised women often feel that many decisions were made over their heads. They also often don’t dare to express their needs or any doubts they might be feeling. But nor does Horsch believe in holding medical staff or nurses responsible across the board for any birth trauma: “The vast majority of staff in the healthcare sector give of their best every day”, she says. In any case, interventions, such as a caesarean, can’t be carried out without the patient’s consent. “But all the same, if a woman feels ignored, it means that the professionals around her have probably failed to give enough space to her concerns”.

Consultations afterwards – and Tetris

Even after the birth, communication remains important. A study conducted by Horsch has shown that even having a single consultation with a midwife in the first few weeks after delivery can significantly reduce the risk of postpartum depression or PTSD. This is why the University Hospital of Lausanne has introduced just such a consultation. New mothers are also now automatically asked two questions shortly after having given birth in order to screen for possible trauma: “Did you feel that your life was in danger at any point during the birth?” and “Were you afraid that your child might die?”

Horsch has also been working for some time on a preventative intervention. She has several times been able to demonstrate that playing Tetris for fifteen minutes after an emergency caesarean means that those affected suffer from fewer flashbacks and are also less likely to develop PTSD. She hopes to be able to introduce this measure in Swiss hospitals soon.