DEBATE

Should students first be taught transdisciplinarity?

If we are going to solve the problems of society, science will have to involve societal actors in knowledge processes. Should students learn this before specialising in their chosen subject?

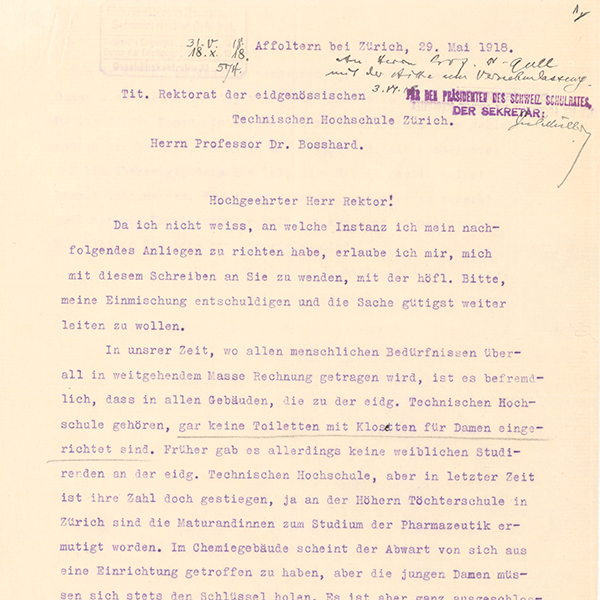

Photo: ZVG

Photo: ZVG

Reality isn’t divided into different, specialised fields. And we need a broad knowledge of all kinds of things to solve problems. The different disciplines are historical in origin, having emerged over time, so the history of ideas is essential from the very outset if we are to understand that disciplinary research is important, but insufficient on its own as a path to knowledge. This doesn’t mean the disciplines as such are going to dissolve away, but rather the ‘silos’ containing their knowledge will – or perhaps they won’t even emerge in the first place.

In Goethe’s Faust, Mephisto tries to convince a student to adopt a stance of uncritical acceptance towards a specific scientific approach: “It’s best here too, if you listen to just one opinion / and swear by that master’s words. / And on the whole – stick to words! / Then you’ll enter through the secure gates / of the temple of certainty”. This seems highly topical to me, because when we study, we encounter dissonance – such as in the seeming contradiction between teaching neoclassical, growth-orientated economics in agricultural or environmental sciences while also teaching about the boundaries of what our planet can sustain. One consequence of this is the widespread assumption that agricultural productivity is incompatible with nature conservation. This dichotomy is also connected to a cognitive separation between human beings and nature. Indigenous scientists tell us that Western science only has a rudimentary understanding of the living world. And it’s true that our science has been perfectly adapted to a world of inanimate objects since the time of Galileo and Newton. If we are willing to open ourselves up to co-creation, we might achieve more than science has managed up to now. For example, we could develop a relational understanding of things, and ultimately a sense of connectedness and responsibility.

Transdisciplinarity recognises different knowledge systems as being fundamentally equal. It can open up our eyes to the idea that there are different perceptions of reality that have different consequences. Of course this should never culminate in anything routine and narrow-minded. Instead, the aim of it should be to promote independence in line with Kant’s principle of enlightenment: ‘sapere aude’: you should have the courage to use your own reason. To offer such an epistemic opening right at the start would thus be empowering.

Johanna Jacobi is an assistant professor in agroecological transitions at ETH Zurich. She is researching into the democratisation of agricultural and nutrition systems.

Before we can start doing transdisciplinary research, we have to be competent in a specific single discipline. Knowledge progresses so rapidly today that our respective fields of competence are becoming increasingly limited. As soon as we have achieved basic competence in medicine, sociology or environmental sciences and have set out on our own research, we realise what expertise we lack. These gaps can be filled by working with research partners. If we are going to solve the problems that affect society as a whole, then transdisciplinary research will be important across all fields, as is also recommended by the OECD. Scientists can then invite the authorities and civil society to participate in the problem-solving process by applying their own practical knowledge. Experience has shown that this usually happens at the doctoral level or later.

It naturally makes sense to familiarise yourself with the basics of transdisciplinarity during your initial studies. But by the time young researchers are ready to apply them, they have probably already forgotten the basics. In my opinion, the most effective way of learning the appropriate methods is at Master level. To his end we have developed an online course with the Network for Transdisciplinary Research (td-net) of the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences.

In practice, it works like this. A PhD student from Palestine learned the basics in our lectures and conducted a participatory, transdisciplinary process on hygiene and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in poultry production in Ramallah. Producers, traders, butchers, veterinary authorities, health authorities and scientists together identified the most urgent problems over several joint sessions. The doctoral student mediated between the different participants and ensured that they were all able to express themselves. He was recognised as an expert and accepted by all as the moderator. A Swiss masters student also participated in the project, during which she learnt the basics of transdisciplinary processes. She will now be able to apply these in further research of her own.

Jakob Zinsstag is a professor of epidemiology at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. He is currently researching into the connections between human and animal health and was recently a science diplomat at the UN.

Photo: ZVG

Reality isn’t divided into different, specialised fields. And we need a broad knowledge of all kinds of things to solve problems. The different disciplines are historical in origin, having emerged over time, so the history of ideas is essential from the very outset if we are to understand that disciplinary research is important, but insufficient on its own as a path to knowledge. This doesn’t mean the disciplines as such are going to dissolve away, but rather the ‘silos’ containing their knowledge will – or perhaps they won’t even emerge in the first place.

In Goethe’s Faust, Mephisto tries to convince a student to adopt a stance of uncritical acceptance towards a specific scientific approach: “It’s best here too, if you listen to just one opinion / and swear by that master’s words. / And on the whole – stick to words! / Then you’ll enter through the secure gates / of the temple of certainty”. This seems highly topical to me, because when we study, we encounter dissonance – such as in the seeming contradiction between teaching neoclassical, growth-orientated economics in agricultural or environmental sciences while also teaching about the boundaries of what our planet can sustain. One consequence of this is the widespread assumption that agricultural productivity is incompatible with nature conservation. This dichotomy is also connected to a cognitive separation between human beings and nature. Indigenous scientists tell us that Western science only has a rudimentary understanding of the living world. And it’s true that our science has been perfectly adapted to a world of inanimate objects since the time of Galileo and Newton. If we are willing to open ourselves up to co-creation, we might achieve more than science has managed up to now. For example, we could develop a relational understanding of things, and ultimately a sense of connectedness and responsibility.

Transdisciplinarity recognises different knowledge systems as being fundamentally equal. It can open up our eyes to the idea that there are different perceptions of reality that have different consequences. Of course this should never culminate in anything routine and narrow-minded. Instead, the aim of it should be to promote independence in line with Kant’s principle of enlightenment: ‘sapere aude’: you should have the courage to use your own reason. To offer such an epistemic opening right at the start would thus be empowering.

Johanna Jacobi is an assistant professor in agroecological transitions at ETH Zurich. She is researching into the democratisation of agricultural and nutrition systems.

Photo: ZVG

Before we can start doing transdisciplinary research, we have to be competent in a specific single discipline. Knowledge progresses so rapidly today that our respective fields of competence are becoming increasingly limited. As soon as we have achieved basic competence in medicine, sociology or environmental sciences and have set out on our own research, we realise what expertise we lack. These gaps can be filled by working with research partners. If we are going to solve the problems that affect society as a whole, then transdisciplinary research will be important across all fields, as is also recommended by the OECD. Scientists can then invite the authorities and civil society to participate in the problem-solving process by applying their own practical knowledge. Experience has shown that this usually happens at the doctoral level or later.

It naturally makes sense to familiarise yourself with the basics of transdisciplinarity during your initial studies. But by the time young researchers are ready to apply them, they have probably already forgotten the basics. In my opinion, the most effective way of learning the appropriate methods is at Master level. To his end we have developed an online course with the Network for Transdisciplinary Research (td-net) of the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences.

In practice, it works like this. A PhD student from Palestine learned the basics in our lectures and conducted a participatory, transdisciplinary process on hygiene and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in poultry production in Ramallah. Producers, traders, butchers, veterinary authorities, health authorities and scientists together identified the most urgent problems over several joint sessions. The doctoral student mediated between the different participants and ensured that they were all able to express themselves. He was recognised as an expert and accepted by all as the moderator. A Swiss masters student also participated in the project, during which she learnt the basics of transdisciplinary processes. She will now be able to apply these in further research of her own.

Jakob Zinsstag is a professor of epidemiology at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. He is currently researching into the connections between human and animal health and was recently a science diplomat at the UN.