ARCHITECTURE

Stone buildings fail the shake test

Earthquake simulations can pinpoint the damage caused to replicas of historic houses, thereby providing the information needed to strengthen them.

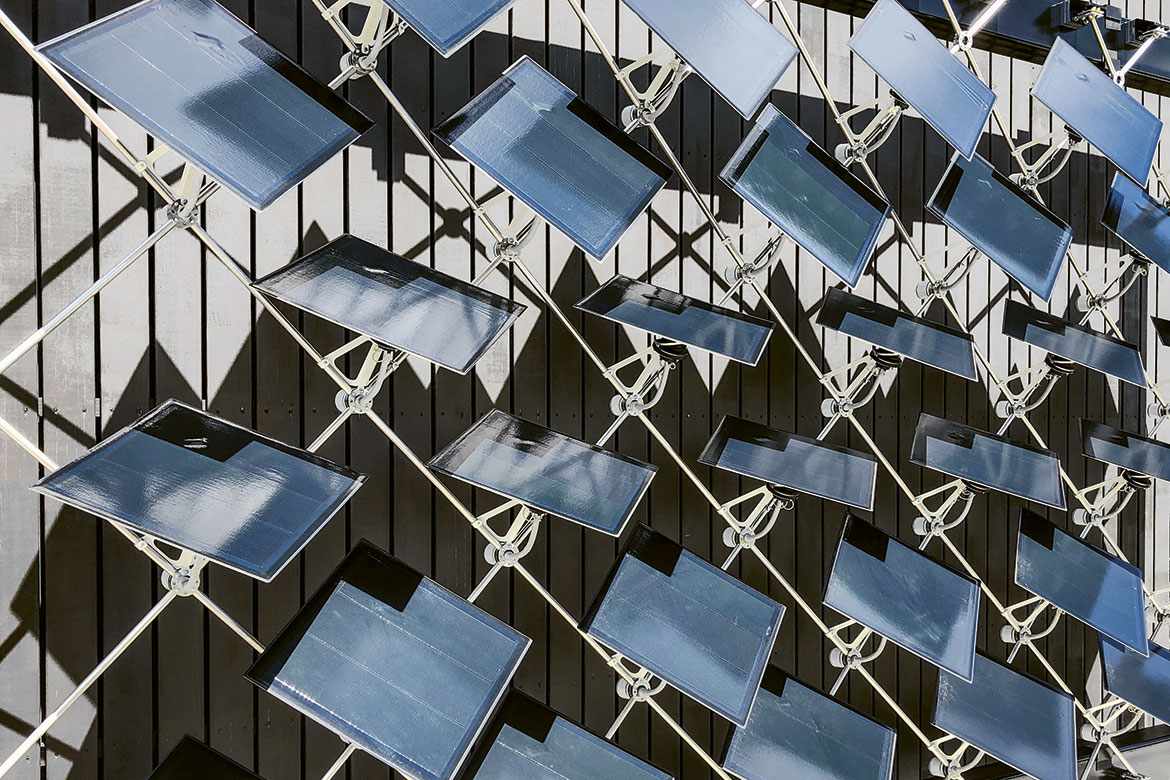

A historic town house has here been rebuilt as a half-sized model for an earthquake test. | Image: I. Tomić/EPFL

When we walk through city centres in Europe, we are often surrounded by old buildings made of stone. They have been built over centuries and carry historical value, yet they are also the most vulnerable to earthquakes. Researchers at EPFL have been simulating the effects of an earthquake on models of these buildings, and have discovered that the problem lies in the damage done when they interact.

“Understanding how these buildings react in an earthquake is important if we’re going to retrofit them efficiently while preserving their historical fabric”, says Igor Tomić. He and his colleagues built a half-sized model of two adjacent units, one of which was over two metres tall, the other over three, and with a total weight of 40 tons. They were made of poorly interlocked stones with just a layer of mortar between them, similar to what is found in historical city centres across Switzerland.

After moving the masonry model onto a shaking table, researchers replicated the 1979 earthquake in Montenegro, shaking it from side to side and from front to back. They detected cracks and separation at the interface of the two buildings that they traced back to the pounding that occurred between them. The taller house was heavily affected by the smaller one, but the researchers were able to strengthen it against larger shakes just by adding a few simple connections between the floor and the walls. “In the future, engineers should consider the interactions between neighbouring historical buildings before fortifying them”, says Tomić.