Report

What the water tells us

In Fehraltdorf, researchers can regularly be seen descending into manholes to explore what lies beneath. They’ve installed a unique network of sensors and measuring stations to observe wastewater. We join them on a tour of the sewer.

The team technician Simon Bloem has levered aside the manhole cover to fetch the data from the subterranean wastewaters of Fehraltdorf. | Photos: Christian Grund

At first glance, Fehraltorf in the Zurich Oberland – population 6,000 – is a little town like any other. There’s a butcher’s shop, two bakeries, four hairdressing salons, and the inevitable two supermarkets – one Migros, the other Coop. At six in the morning and six in the evening, there are traffic jams on the main road here – and that’s pretty much as eventful as it gets. Yet this perspective of the place is superficial in the literal sense of the word. And it’s not entirely correct. Top-class international research is in fact being carried out here, beneath your feet.

Fehraltorf is the world’s first and so far only outdoor laboratory for wastewater research. Its official name is the ‘Urban Water Observatory’, though its nickname among those who work there is ‘Uwo’. It was set up in 2016 by ETH Zurich and by the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Dübendorf (‘Eawag’). The lab’s current project manager is Jörg Rieckermann, an environmental engineer. He says that their work focuses essentially on a simple question: What happens to the contents of your toilet after you flush? “Most people don’t know the answer, and not even we researchers know exactly”.

Radio signals from the sewer

This question is extremely important, because a potentially dangerous mixture is flowing beneath our feet. It is comprised of everything expelled by our bodies and our environment: viruses and bacteria, the residues of drugs and hormones, the wastewater from washing machines and dishwashers, and our shower water with its residues of body fat, skin cells and hair. Then there’s the detritus from the wear and tear on our car tyres and the pesticides from our gardens, verandas and fields – everything that the rainwater washes away.

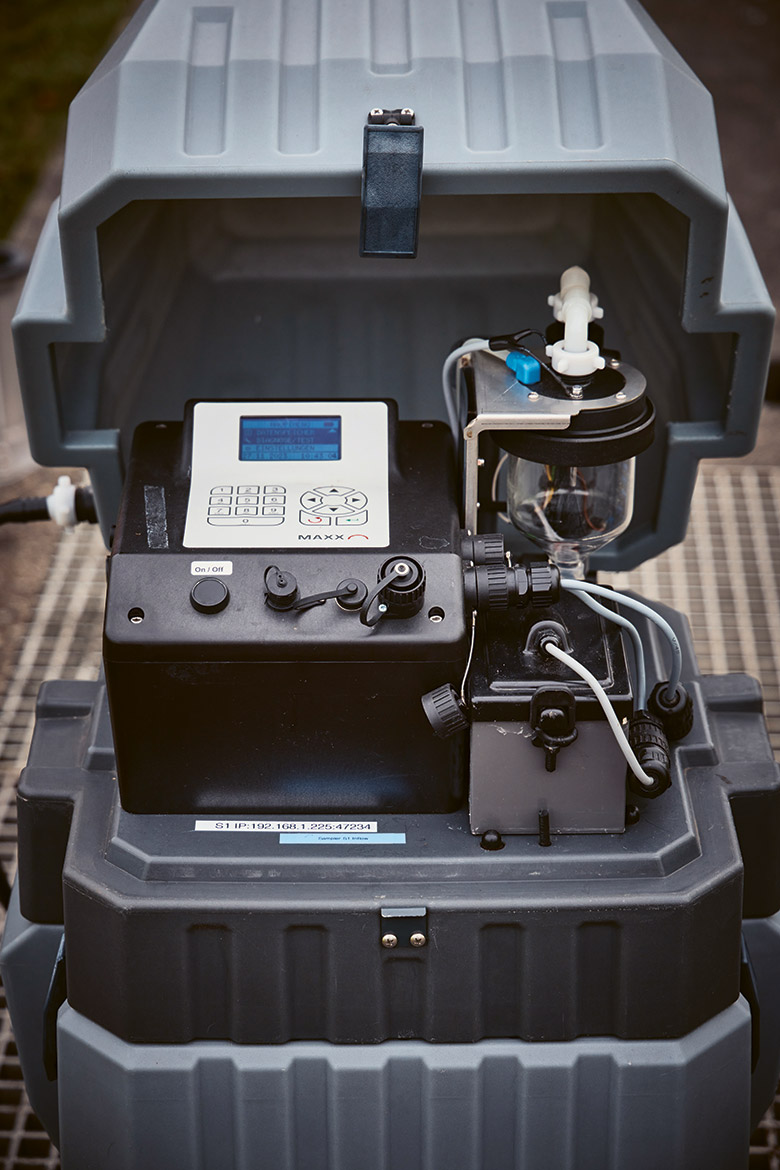

In order to find out what happens to this toxic cocktail before it is treated in the sewage plant, Rieckermann and his team have installed dozens of sensors in the sewers under Fehraltorf. Simon Bloem is currently working his way towards one of them. He’s a graduate in mechanical engineering and the team’s technician. Using a pick, he levers aside the 50 kg-heavy, cast-iron manhole cover in the Bahnhofstrasse. It’s a five-metre drop from here to the bottom of the sewer, and you can hear a stream rushing past in the depths – that’s the wastewater of Fehraltorf.

Roughly one metre above the flowing waters there hangs something that looks like a household iron. “It’s a Doppler radar”, says Bloem. “It works like the cameras the police use to measure the speed of cars, and we use it to determine the flow speed and the level of the wastewater”. Other sensors measure the electrical conductivity of the sewer, because this can provide information on the nutrient content and thus also on the quantities of pollutants being transported by the water.

The data is transmitted by mobile radio every 12 hours. The sewer’s concrete pipes and manhole covers weaken any signal sent from here, so the research team has installed its own radio network to ensure that the signal reaches the surface. “It’s unique in Switzerland”, says Bloem.

It’s a fact that there has been little previous research into wastewater flows, their fluctuations or composition. Municipalities and cities have to review their drainage plans every 10 years to ensure that their wastewater doesn’t spill out into the open, even when there are heavy rains. “But they generally utilise only model calculations without comparing them to actual physical measurements”, says Rieckermann. That means that most municipalities are flying blind, and their lack of knowledge can sometimes prove costly. “In Fehraltorf, they were planning on installing larger pipes for one section of the sewer, based on their model calculations. It would have cost some CHF 200,000. But our measurements showed that the renovations weren’t really necessary”, says Rieckermann.

Small towns like Fehraltdorf aren’t introducing such ‘real-time’ wastewater measurement systems across the board, not least because of what they cost. Bloem picks up the sewer hook and uses it to fish a black box – the size of a shoe box – out of the shaft. “That’s the battery”, he says. “I have to replace it once a month”. That means driving here, cordoning off the area, opening the manhole cover, and so on ... Then there’s the cost of the equipment. The Doppler radar alone costs CHF 10,000. Maintenance and operating costs are a further CHF 20,000. “It’s just not worth it for the municipalities”, says Rieckermann.

Pollutants in the town stream

This is why the researchers in Fehraltorf are focussed on the further development of their sensors. Bloem now pulls up a black capsule from below that’s the size of a small plastic PET bottle: “This contains our new sensor, including the electronics and the battery. It will last for a year and a half”. It costs CHF 2,300 per unit. “This will make monitoring affordable for municipalities in the future”, says Bloem.

But heavy rainfall isn’t just a problem for villages and towns. It also has an impact on the surrounding countryside. You can see this when you leave the town and venture just a kilometre further up the hill outside it, where there’s a fenced-in area with a concrete floor and a cover grille. We’ve come here with Lena Mutzner, an environmental engineer specialising in rainwater pollutants. “There’s an overflow basin under here”, she says.

This basin is like the relief valve of a pressure cooker. If too much rainwater flows into the drains, it spills out here, from where a relief channel leads it directly into the town stream. This prevents the town’s mixture of rainwater and wastewater from overloading its sewer network and flooding the streets. But it also means that some of the sewage is discharged untreated into the stream and then, from there, into the nearest river or lake. Mutzner says there are some 5,000 such overflow sites across Switzerland.

“I’m trying to find out how many pollutants we can transport to the sewage treatment plant before any overflow occurs. And how many of them actually end up in the stream”. These pollutants include the active ingredient Diclofenac (also known as Voltaren), which is used in many painkillers and can harm aquatic organisms even in low concentrations. The same applies to Diuron, a herbicide and algicide that is used in agriculture but is deemed to be highly toxic to aquatic organisms. No one yet knows the precise quantities of these substances that enter the environment through the overflows.

Kitted out like cave explorers

Mutzner makes her measurements by taking samples at regular intervals, a task performed by a sampling device the size of a refrigerator that is connected to the wastewater flow by a hose. But actually obtaining the data isn’t always so easy. So Mutzner also works with so-called passive samplers. These look like small scraps of paper that have been clamped between two metal plates. The paper absorbs the pollutants, which can later be analysed in the laboratory. In order to install these samplers, Mutzner has to go down into the overflow basin. It’s like exploring a cave. She’s kitted out with a helmet, a safety harness and a gas warning device before descending into the shaft. “The warning device tells you if there’s an increase in the level of CO2 or other gases that could be dangerous for us”, she says.

The shaft leads into a kind of air raid shelter for toddlers, with a ceiling height of some four feet. The only way to get through it is to squat. There’s a tart note of rancid wine in the air. Mutzner reaches an anchorage point and screws the metal plates onto it. “The next time it rains, this whole space will be full to the brim with sewage”. The passive collectors will also be swamped. This excursion into the depths shows just how difficult it can be to engage in wastewater research.

“You need protective equipment and the right materials, and you need to know how to move around safely underground”, says Rieckermann. “We here have a unique opportunity to make all of this knowledge available to a global research community”. Since it was set up, experts from half a dozen countries have already worked in Fehraltorf’s outdoor laboratory, coming variously from Germany, England, Austria and China.

Every now and then, a product developed at Uwo manages to make the leap onto the international market. Christian Ebi is the team’s electronics engineer and he explains the ‘Squid’ to us. It’s a plastic ball about the size of an orange that can float and is packed with electronics and sensors to measure the temperature, acidity and conductivity of wastewater. “We drop these balls into the sewer from above, and fish them out again down by the sewage treatment plant”, he says.

They record data as they travel through the underground sewers. The international wastewater and recycling company Suez now uses them to inspect the sewer networks of different cities for leaks, and to investigate the volume of discharges and their nutrient content. They’re making an important contribution to the safety of people and the environment – and it all began underground in Fehraltorf.