REPORT

In the corridors of the museum

Vaud’s archaeological treasures live double lives at the Palais de Rumine. Whilst the general public can view them in the museum’s exhibits, we were welcomed into its cellars where they’re restored and studied.

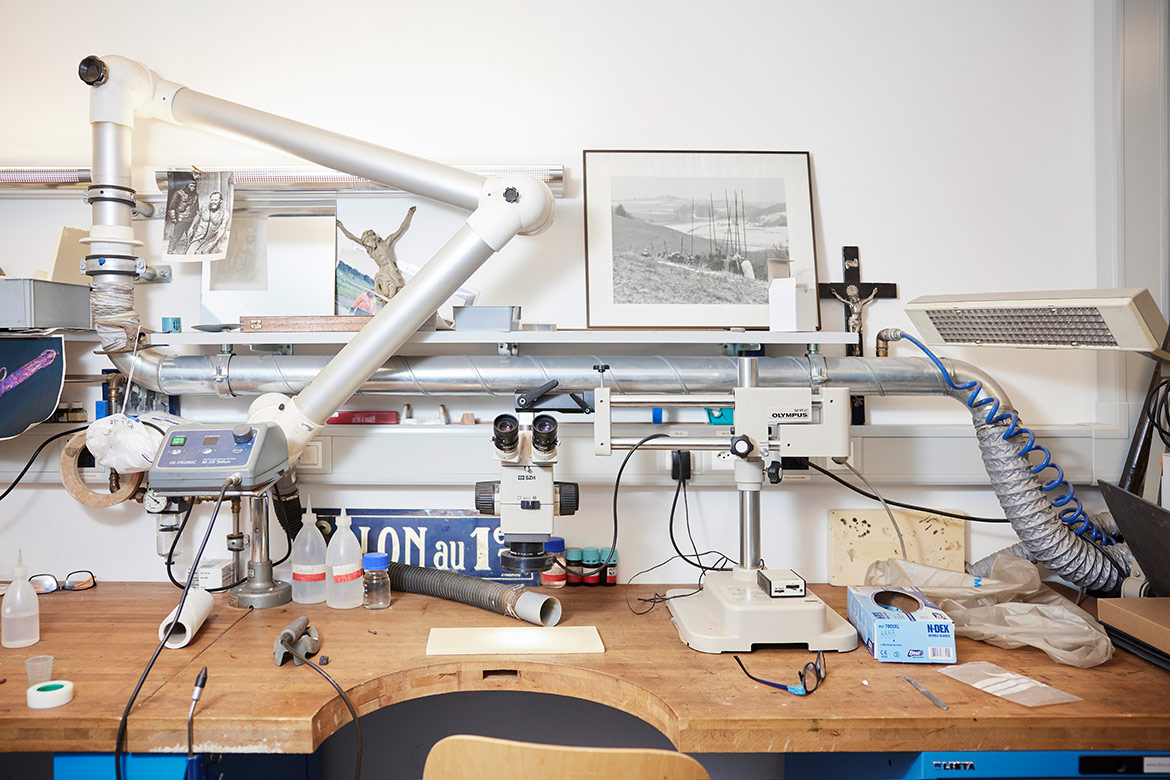

In the restoration lab, layer after layer has to be removed carefully if this key from Roman times is going to shine in new splendour. | Photos: Marion Bernet

Asking David Cuendet questions requires waiting. He’s sat at a sandblaster with his hands inside its glass case in a state of extreme concentration. He’s gripping the nozzle of the blaster delicately with his fingers and spraying its jet over a metal object with great exactitude. As it moves, millimetre by millimetre, it strips the artefact of its encrustation, a dark layer with rusty highlights. The contours of this long item are still relatively shapeless, even when magnified by the loupe, making it hard to imagine that it might soon find its place exhibited under strong light in a glass case just a few floors up. For that matter, it’s hard to imagine that the visitors to the Vaud Cantonal Museum of Archaeology and History – situated in the centre of Lausanne in the imposing Palais de Rumine – would immediately identify it as an exceptionally old key.

For now, the key is in transit through the shadows of the rooms occupied by the museum’s conservation-restoration laboratory, headed up by Cuendet. “It’s about 2,000 years old, that’s the Roman period, and it was found in Vidy-Boulodrome, a dig used to train archaeology students from the University of Lausanne”, he says later, having switched off the machine and removed his hands from the latex gloves. The aim of sandblasting, which actually employs glass pellets, is to remove the corrosion preying on the key, down to its surface, and to reveal its original shape. And, in the same breath, to obtain more precise information about its age and how it was used. But to bear this out, Cuendet will need to employ his specialist skill in this painstaking task for a few more hours.

Down with interventionism

The lab currently employs five staff members and five assistants. It’s not just responsible for the preservation of the artefacts discovered during archaeological excavations, but also for following up the museum’s collections. “We’re right in the middle of the chain; we’re the interface between the teams upstream, particularly those on digs, and teams downstream, for instance, those working on exhibits”. This mission often calls on them to be acutely diplomatic, says Cuendet, winking an eye. And acrobatic too: “to ensure our work doesn’t hold up digs, we often must do it in parallel, even sometimes on the ground”. This is the case on the vast excavation site in Lausanne at Prés-de-Vidy, a project that will stretch over four years and eight hectares, starting at the end of June 2024 prior to the construction of neighbourhood housing.

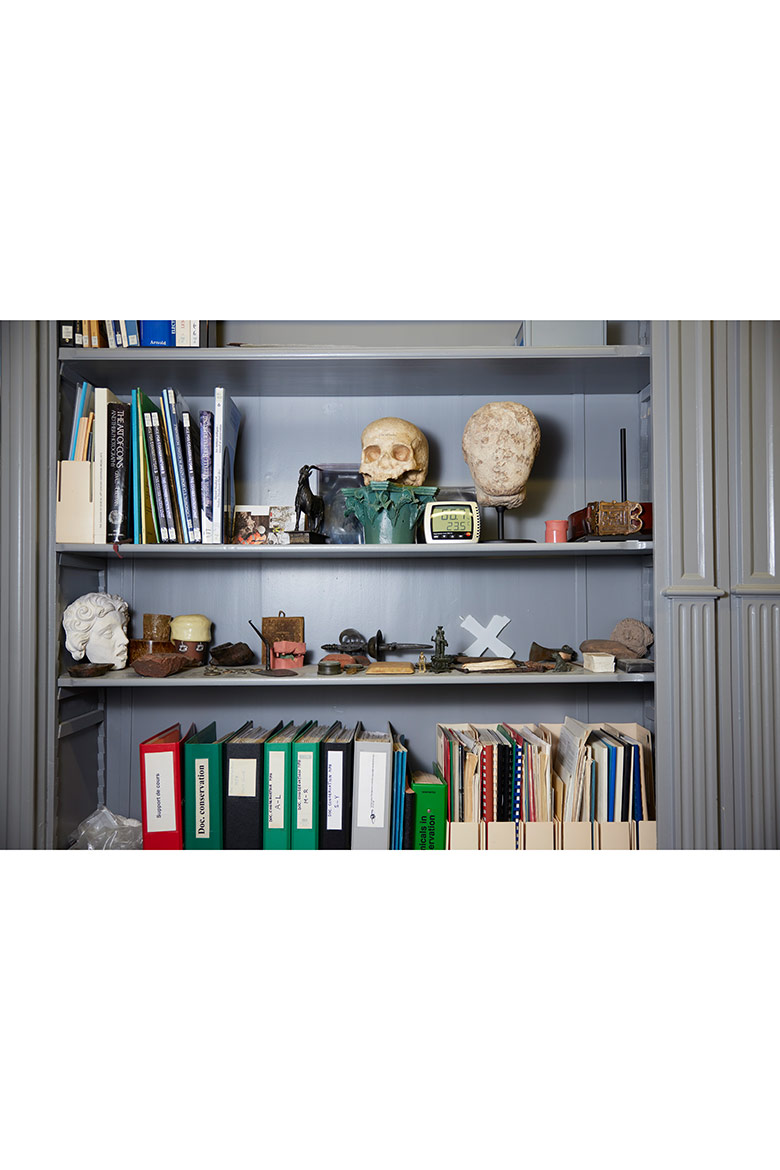

According to Cuendet, conservation-restoration “responds to a scientific demand”, i.e., transmitting material cultural heritage to future generations, safeguarding it, documenting it and making it accessible. When he started out his career, there was no specific training. That’s since changed and today the ropes can be learned by following a UAS Masters. The curriculum is varied, as it looks at preventative conservation, curative conservation and restoration.

Preventative conservation aims to avoid the future decay of artefacts found on excavations, by strictly controlling humidity in storage facilities, for example. Curative conservation aims to stop the processes of decay already under way, for example, by chemically stabilising corroded metals. “The key I am working on at the moment will probably undergo stabilisation”, says Cuendet. With regards to restoration, its aim is to increase our understanding of an artefact or asset, for example, by reassembling the pieces of a broken ceramic vase.

It is noteworthy that each conservation-restoration measure is decided upon “following an interdisciplinary group process” that allows the greatest possible collation of data and realities, he says. In particular, it involves archaeologists, anthropologists, conservator-restorers, museum curators and historic monument conservators. Having spent almost 30 years in the Museum, Cuendet has seen the job change. “Over the years, we’ve become increasingly less interventionist”. The aim of restoration is no longer to revert objects to their original state but to help place them in their original setting. “This is because objects have no meaning outside of their context”. In the case of the key he’s working on, restoring its exact shape may allow associations to be drawn with other objects found during digs “and to understand why and how it was used, to reconstitute a small piece of history”. Conversely, “a broken vase whose function is manifest won’t be rebuilt at all cost, and where it is, the repair will remain clearly visible”.

Technology to the backup

To support their research, conservator-restorers rely on a number of laboratory techniques, including tomography, an imaging method that identifies the material composition of an artefact. This technology, provided by EPFL, has allowed them to identify organic remains in the rust of three swords displayed in a temporary exhibit at the museum. These items belonged to the ancient La Tène culture (fifth to third centuries before the modern era) and were found during digs at Denges in 2021–2022.

Then there’s radiography, which has become overwhelmingly important in recent years. Cuendet and his colleagues don’t even need to leave the building to use it anymore. He places the ancient iron key in a specially designed box, passes through several doors and takes us down several flights of stairs before striding along a lengthy corridor to a room where the equipment was installed two years earlier. From its shape and size, it is reminiscent of a home sauna.

A member of the team opens it and places the key inside. A few seconds later the antique artefact is displayed on a screen. Under the thick and shapeless layer of rust, we can see the outline of the object and the details of its construction. “Radiography is a precious tool that allows us to gather sufficient information to identify an object without having to clean it, and, at the same time, to define the conservation-restoration treatment priorities”. By using this technique, it is for instance possible to determine whether funeral urns contain artefacts potentially of interest in and of themselves, such as a bracelet. “In the enormous dig at Vidy, this will mean welcome stitches in time”.

From nuclear to archaeological

Without further ado, Cuendet recovers the valuable key, still snug inside its custom-made case. As he’s doing it, he describes how designing boxes for storing artefacts is also part of the lab’s mandate. The thousands of treasures dug up during archaeological excavations are stored at a location made available by the authorities of Vaud inside a disused nuclear power plant in the commune of Lucens. This is also where curators come ‘shopping’ according to their chosen themes. The conservation-restoration lab is then responsible for evaluating what measures must be taken to ensure the artefacts survive their exhibition: type of showcase, intensity of lighting, level of humidity, security requirements, etc.

When loaning to other museums, in Switzerland or elsewhere, Cuendet and his team work in close collaboration with their external counterparts. “Sometimes, we simply have to refuse any movement, for example, when an object is too fragile”. In other cases, exceptional measures must be taken. Cuendet recalls a famous and expensive example: a gold bust of Marcus Aurelius, the jewel in the crown of Vaud’s archaeological heritage, which was loaned last year to the Getty collection. “Both the directors of the Roman Museum of Avenches and of the Vaud Cantonal Museum of Archaeology and History travelled to the United States by plane with the case containing the bust”, to ensure its security.

Before returning to his sandblasting, Cuendet takes us on a detour through the room where, if necessary, stabilisation is performed. “It’s done when artefacts are particularly fragile or their decay is at an advanced stage”. They’re submerged in tanks that contain sodium sulphate and sodium hydroxide, which enables the dissolution and extraction of chlorides. “It stops the object from shattering due to the crystallisation of salts trapped in the corrosion”. Despite all of the many precautions that are taken beforehand, the procedure still runs a risk of damage. “This means we first scrupulously detail the artefact in question, so as to avoid all loss of information”.

Cuendet calmly says: “In any case, at some point, every object meets its destiny to be destroyed”. Conservator-restorers may indeed slow down the process, “but cannot avoid it, because it’s the way of things”. The aim of the job, therefore, is “knowing where we’re coming from to know where we’re going to”.