Feature: Water bargaining

Water: the lifeblood of peace

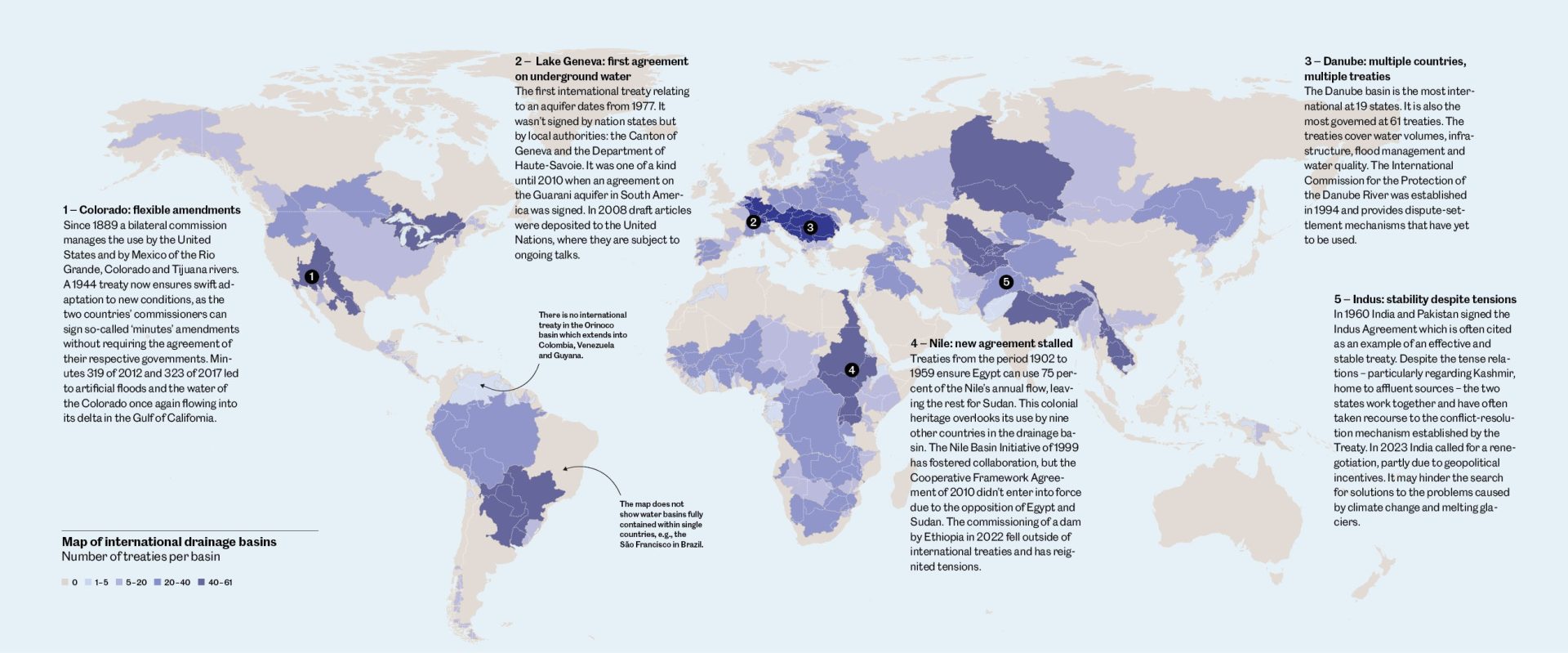

Ensuring sufficient flow, coordinating infrastructure and protecting the environment: hundreds of agreements govern transboundary river basins. This technical cooperation continues most often despite elevated geopolitical tensions.

- Source: ‘Agreements in International Transboundary River Basins’ (2024), Transboundary Freshwater Diplomacy Database, Oregon State University

The real absence of water wars is partly due to international treaties. “Research shows that they are an effective instrument for promoting collaboration between States, even when they have difficult relations”, says Melissa McCracken, a professor of international environmental politics at Tufts University (USA). She is part of a team that manages several databases on the diplomacy of fresh water, which cover 300 waterways and their related conflicts, instances of cooperation and treaties.

These tools help us to improve our understanding of the drivers of conflict over water and the mechanisms that encourage cooperation and sustainable governance. One important aspect is that the agreements shift the discussions from the geopolitical – i.e., territorial – arena and into the one on infrastructure. “Often, water is managed at the technical level, rather than the political level, which can help to maintain relationships for effective cooperation without the issues becoming as politicised”.

Illustration: Bodara