LONG COVID

The never-ending pandemic

Even now, almost three years after the end of the coronavirus measures in Switzerland, some people continue to suffer from the consequences of an infection, and others are still contracting Long Covid. We’ve been trying to find out more.

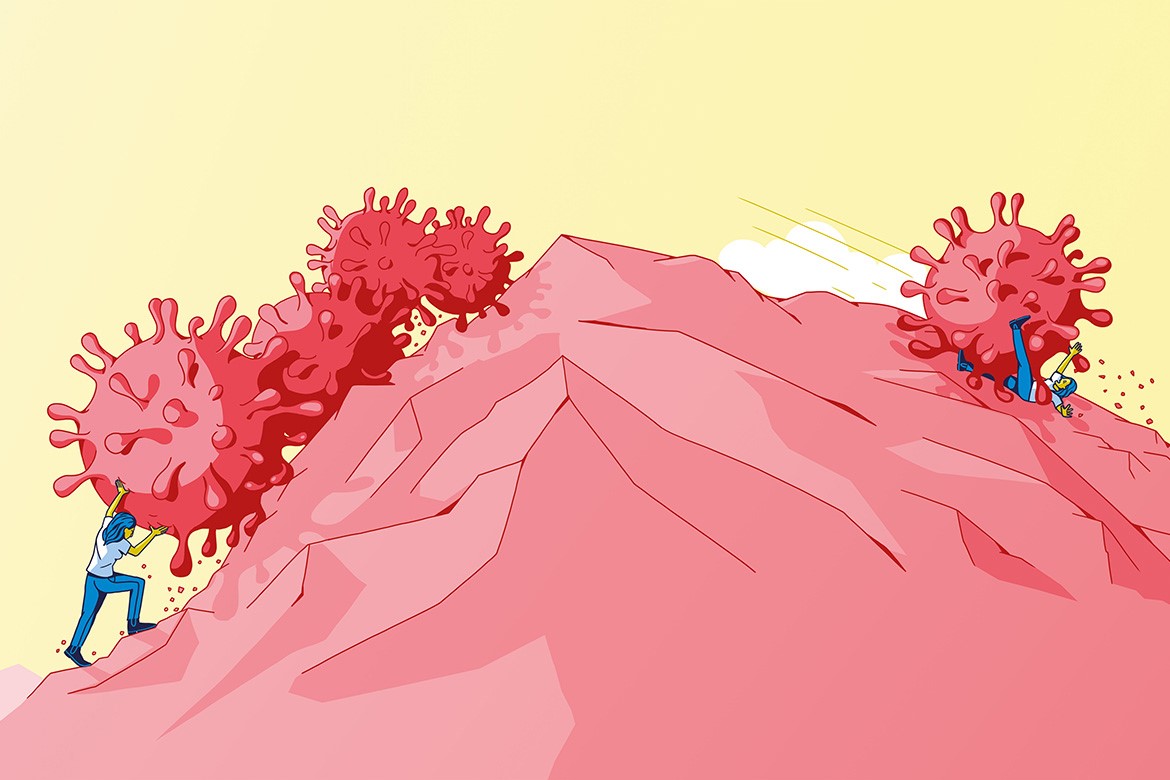

The acute phase of the pandemic demanded immense efforts across society. And people are still being overwhelmed by Long Covid to this day. | Illustration: Christina Baeriswyl

The novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2 had barely begun to spread around the globe back in March 2020 when initial reports emerged that this disease could have long-lasting symptoms. Patients themselves coined the name ‘Long Covid’ to designate a complex of symptoms persisting beyond the acute phase of infection. It is also referred to in specialist literature as the ‘post-acute sequelae of coronavirus infection’, ‘post-acute Covid-19 syndrome’ or simply ‘post-Covid’. The World Health Organization defines Long Covid simply as those symptoms that still persist three months after an infection, that last for a total of at least two months, and that cannot be explained by any other cause. This is an extremely vague definition that demonstrates the difficulties faced by researchers, the medical profession and society overall when trying to get to grips with Long Covid. We have spoken to two people who have been affected by it. We then focus on six different topics to try and get to the bottom of the phenomenon.

![]()

- Biologist, professor, institute director (56), male, sick for four months (*)

“I got off lightly”

“In early 2024, I came down with Covid for the third time and was slow in recovering. If I carried my shopping up the stairs, I immediately had to go and lie down in bed. I also kept making stupid mistakes. For example, I sent a confidential email to the wrong people. I kept working from home but did a lot less and in dribs and drabs because I couldn’t concentrate for any longer period of time. My team worked really well, which is undoubtedly also due to my management style. My university environment was very accepting.

“I didn’t take any medication. I ate even more healthily than normal and very slowly started doing my gymnastics exercises again. After about four months, I was back at my normal level. Now I’m working as usual, I’m writing publications and I’m going to conferences. I’m researching into viruses myself, so I’m aware that I got off lightly. I’ve become more careful – and in public transport and in planes, for example, I now wear a mask”.

(*) The name of this person has been withheld but is known to the editors.

Illustration: Christina Baeriswyl

![]()

- Social scientist, professor (56), female, sick for the past two-and-a-half years (*)

“Like a never-ending lockdown”

“The first few months after my Covid infection were a nightmare. I had no idea and was just stumbling from one disaster to the next. I couldn’t grasp a single line of text. I was suffering from brain fog around the clock, along with severe pain and exhaustion; I was dead tired, had a sleep disorder, and much more besides. I went into rehabilitation but didn’t get any healthier. Since I became ill, I’ve been working from home for a few hours a day, with long breaks in between. My colleagues are supportive, and the director of my institute at my university of applied sciences is very sympathetic towards my problems. But I’ll probably have to give up my professorship sometime soon. And that hurts a lot.

“I can’t go for a pizza just on a whim, nor can I have an evening out with a girlfriend. None of that is possible any more. It’s like I’m in a never-ending lockdown. My husband is a big help and makes me feel like our lives are still worth living. My professional background means that doctors take me seriously. But others find it more difficult. That’s also why I’ve become involved in the Long Covid Association here in Switzerland, which is fighting for social recognition and a better care system. The worst thing is when someone says, ‘why don’t you just go out in the sun a bit more?’”.

(*) The name of this person has been withheld but is known to the editors.

Illustration: Christina Baeriswyl

A lack of data on the extent of the problem

Switzerland, like most other countries, has failed to collect systematic data on Long Covid. This naturally makes it difficult to quantify those who are suffering from it. A comprehensive analysis has nevertheless been undertaken, showing that about six percent of all adults across the globe and one percent of all children have suffered from long-term effects of Covid, or are still suffering from them. These figures are derived from statistical surveys in the USA and the UK and from meta-analyses of large-scale cohort studies. It seems likely that the number of cases in Switzerland is similar – estimates here for those affected range from 80,000 to 450,000 people.

The data on the progression of the disease are even less certain. A Swiss cohort study of 1,100 unvaccinated people with Long Covid found that roughly 17 percent of them still did not feel fully fit after two years, although most of them registered an improvement in their condition. There are also no data on what Long Covid is costing the Swiss economy and healthcare system.

Illustration: Christina Baeriswyl

Immune system constantly at full blast

The search for the cause of Long Covid has gone on for four years now. In January 2024, Onur Boyman and his team at the University of Zurich were able to chalk up a success when they found that blood samples from Long-Covid patients revealed changes in the proteins belonging to a part of their immune system. It’s our first line of defence against bacteria and viruses – the so-called ‘complement system’ – and is activated in healthy people when they get an infection. “In patients with Long Covid, however, the complement system doesn’t return to a resting state after an acute infection”, says Boyman. “And those patients in whom it does indeed return to a normal resting state aren’t suffering from Long Covid”. Boyman also talks about other possible causes: a disturbed intestinal microbiome, reactivated herpes viruses or autoimmune diseases. But for him it is clear: The complement system is central to many symptoms.

Ziyad Al-Aly works at Washington University in St. Louis (Missouri, USA) and began researching into Long Covid early on. And he is a little more cautious: “[the complement system] is certainly an important mechanism, but I hesitate to say that it really is the main one”. Either way, it would be a suitable target for a drug. “The question is, what triggers this overactivation of the complement system?”. In addition to the obvious damage caused by an acute infection – e.g., scarring of the lung tissue – there are also indications that the coronaviruses or at least parts of them remain in the body, where they continue to trigger the immune system. In any case, there are still far too few data, says Al-Aly. This uncertainty is also reflected in the 43 different definitions of Long Covid that his group has counted.

Recurring fatigue

Meanwhile, it’s clear that Covid-19 can trigger chronic fatigue syndrome, which today is considered to be a disorder alongside myalgic encephalomyelitis, referred to jointly as ME/CFS. The core symptom is exercise intolerance. Those affected can only go shopping for a short time, for example, or take a short walk. And by the evening, or the next day, they feel utterly exhausted. In severe cases, people can become completely bedridden. Christian Dungl is the senior physician at the Hasliberg Rehabilitation Clinic, and he began seeing cases like this even before the Covid pandemic. When polio used to spread, people spoke of atypical poliomyelitis; today we have fibromyalgia or cancer-related fatigue. There are many triggers and they have similar symptoms. Besides exercise intolerance, people suffer from general fatigue, problems concentrating (‘brain fog’), and so-called vegetative disorders e.g., tachycardia, digestive problems, pain and hypersensitivity.

Besides the immune and hormonal systems, the central nervous system is also involved. It processes signals to and from the body. But in cases of chronic fatigue, the neural defence system is overactivated in what Dungl terms ‘central sensitivity syndrome’. This typically affects people who are highly active in many ways, “and whose nervous system is already running at a hundred miles an hour around every bend. And then the virus arrives alongside everything else”. Dungl’s therapeutic approach involves teaching his patients to know when their body is telling them they’ve reached their limits, so that they don’t keep exceeding them all the time. He has been able to observe a slow but steady improvement in many of them – but it takes months, not weeks.

Illustration: Christina Baeriswyl

Getting all the experts together

“The symptoms of Long Covid are highly heterogeneous”, says Katrin Bopp, the founder and head of the ‘Post-Covid/long Covid clinic’ at the University Hospital Basel. This is why the first step is to construct a thorough case history, not least because it allows doctors to rule out other possible causes and identify pre-existing conditions. “There is no clear diagnostic criterion, which is often frustrating for everyone concerned”, says Bopp. So it’s all the more important, she insists, to make those affected realise that they are not imagining their symptoms. “The goal of our treatment is to improve people’s functionality in everyday life. In other words, we focus on what’s still possible”. To this end, she brings in experts from different fields – medicine, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and psychology. Getting the costs of treatment reimbursed by health insurance companies is not normally a problem, says Bopp. But she wishes there were more money to train staff to treat fatigue disorders. They are much in demand, and the waiting list for her clinic is some two or three months long.

Even more resources will potentially be needed in the years to come. At the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG), Julie Peron’s team of clinical neuropsychologists has identified individuals with measurable attention deficits and visible changes in the brain, but who do not feel at all ill. “These symptoms can be seen in neurological disorders such as neurodegenerative diseases”. An increase in cases of this type of disease in coming years would therefore give rise a plausible hypothesis.

A discriminatory virus

Covid-19 affects men more severely than women, and it’s also men who more often die from it. This can be partly explained by biological differences in the immune system. Catherine Gebhard is a cardiologist at the Zurich University Hospital. She and her team have been investigating the influence of gender on cases of Long Covid, and they have ascertained that it’s women who are more likely to suffer from it. But it’s difficult to find the reason. “It has nothing to do with sex hormones, that’s for sure, as we checked this during our study”, says Gebhard. This is why they have also investigated the social circumstances of those affected. And they indeed found that the risk of Long Covid increased, regardless of gender, in cases where people had a low level of education, among single parents, and among those without any children. But it’s women who are more likely to belong to these groups. Matters become interesting in cases where people live alone: in women, this proved to be a risk factor, whereas among men it was a protective factor. Similarly, having the highest income in a household only served to protect men, not women.

Gebhard attributes this to stress. People become more susceptible to Long Covid when they feel lonely or that they’re failing to meet society’s expectations of them. “Our study has led women to accuse us of perpetuating the typical notion that we find biological factors in men, but ‘only’ socio-cultural factors in women”, says Gebhard. But she insists that her study by no means rules out the possibility of unknown biological factors; it simply shows once again the importance of living conditions.

Illustration: Christina Baeriswyl

Lots of ideas for therapy, but no data

There still isn’t any medication approved specifically for Long Covid. “Of course we’d prefer to have a therapeutic measure that tackles the root of the problem”, says Dominique de Quervain, a neuroscientist at the University of Basel. But there is no prospect of one as yet. This is why doctors mainly resort to drugs or therapies that are already known. For example, a Genevan company has conducted a clinical trial with an antibody that was actually developed to treat multiple sclerosis (MS). But it didn’t have the hoped-for impact against fatigue. The University of Basel planned a study with Fampyra, a drug approved for MS that could help patients with cognitive problems. But it proved impossible to recruit enough participants. When Chinese researchers conducted a study in which they modulated the gut microbiome with benign bacteria, however, they found it had a positive impact on fatigue and concentration disorders. Meanwhile, researchers have also identified certain preventive measures that are effective against Long Covid. They know that vaccination has a protective effect, although it remains unclear whether an annual booster is beneficial. And taking the antidiabetic drug Metformin lowers the risks for overweight people.

The Long Covid Association of Switzerland lists a number of potentially helpful treatments; they are, however, mostly just based on people’s personal experiences. “It would make sense to conduct a controlled study on these therapies”, says Milo Puhan, an epidemiologist at the University of Zurich. “It could prevent those affected from spending a lot of money on something that doesn’t work”. This is why his team is currently conducting a study on the natural substance pycnogenol, which supposedly has an anti-inflammatory impact. They were also planning a study on dialysis, as there have been reports that this method – which filters certain substances out of the blood – can help with Long Covid. It failed to come about because of a lack of funding. But all the same, Puhan isn’t so gloomy about the future: “Reputable randomised studies simply take time. And many rehabilitation measures are already helping patients with Long Covid”.