Collected editions

A text is no finished work

Scholarly editions have long served to collect and make public the writings of well-known authors. But today, such editions are increasingly being restricted to letters. These projects take less time to complete and can shed light on seemingly marginal issues.

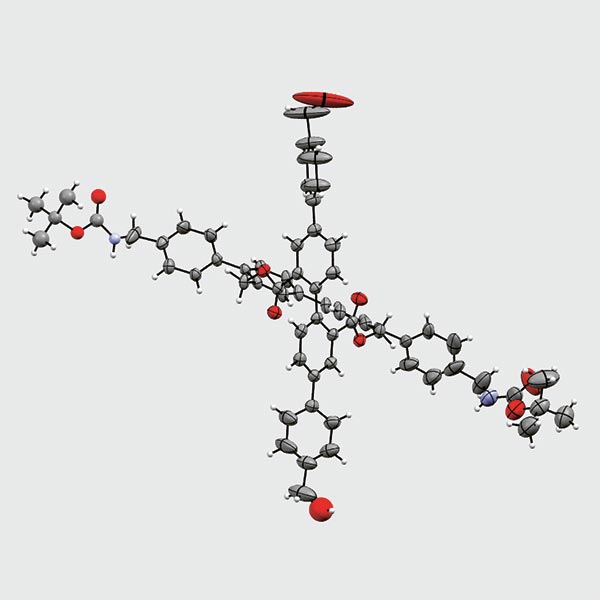

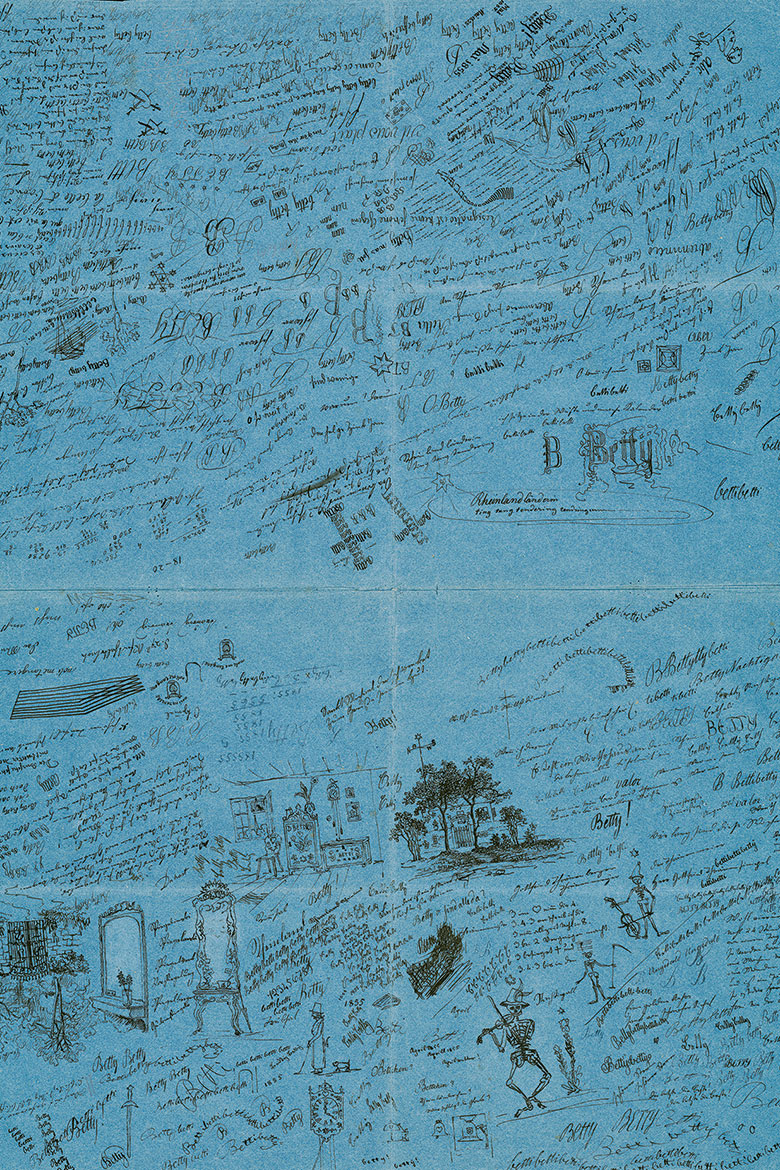

With Gottfried Keller, even his blotting pad in Berlin (ca 1855) became a text. Source: Manuscript Department of the Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Ms. GK 8b)

When Johannes Kabatek first saw the roughly 20,000 letters received by the Romanian scholar Eugenio Coșeriu, they were packed in removal boxes in Tübingen. But he knew for certain that they were a vital source for the history of linguistics in the 20th century and that at least a portion of them simply had to be published. In 2024, after just four years, the project ‘Digital Letters to Eugenio Coșeriu’ was finished and its contents available online. “Coșeriu renewed the field of semantics from his home in Uruguay by corresponding with people”, says Kabatek. This was something that no one had previously suspected. Kabatek is a scholar of Romance languages at the University of Zurich and a former student of Coșeriu himself.

With the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), Kabatek and his team of researchers have compiled a pragmatic edition of these letters without any extensive commentary. “Our prime aim was to transcribe the manuscripts”, he says. These transcripts are now available to the scholarly community – though his group has also meanwhile engaged in research into the letters because their editorial project was also a research project.

Improvements that make things worse

Making scholarly editions constitutes important basic research in the humanities. Ultimately, they revolve around the question of what a text is and how it is created. Textual criticism is interested in how a text has come about, which version of it ought to be regarded as the valid one, and for what reasons. These criteria apply, regardless of whether the resultant edition is published in book form or online. One might also say that there is no such thing as ‘the’ text, because texts usually exist in several variants, with their authors deleting or inserting phrases.

This happens not just with well-known novels, but also with letters. Sometimes, friends or publishers change passages against the author’s will, and even make things worse by making mistakes when they do so. How should an editor deal with that? There are several schools of thought in the field of textual criticism. One approach involves attempting to reconstruct the texts as the authors published them for the first time. In these editions, texts are accompanied by a commentary (either long or short) on the historical context, the origin and reception of the text, and the life of the author.

Another school of thought, however, believes in reproducing – as accurately as possible – the changes that authors make to their texts. The aim in this case is to trace the authors’ writing processes. Scholars who adhere to this approach tend not to be interested in providing any commentary. In contrast to these two options, a transcription, as realised by Kabatek, just aims to make texts accessible quickly and easily.

At present, digital editions of letters are popular – such as the Coșeriu project. They usually encompass a manageable body of texts – or a body of texts that can be made relatively manageable by making an appropriate selection. Such editions can be realised using existing editorial methods.

Publishing authors’ correspondence also opens up perspectives on the other writers with whom they were engaged in a dialogue. This in turn makes networks visible and can shift the focus to women, who have generally been underrepresented in the traditional major editions. We can observe this, for example, in the four-volume edition of the letters of Julie Bondeli, a Bernese intellectual and patrician from the 18th century. The notion of monolithic editions focusing on the ‘life and works’ of ‘great men’, such as used to dominate the literary landscape until around the year 2000, is thereby being eroded.

Expanding the canon

“These days, the relationship between the author and their work is viewed in a more differentiated way”, says Ursula Amrein, a scholar in German studies based in Zurich. She was the deputy project manager of the 32-volume ‘Historical-Critical Gottfried Keller Edition’, which was completed in 2013. In a move that was innovative at the time, this edition was published not just as physical books but also digitally. This flagship edition of Keller’s works took some 15 years to complete. It is indispensable for our understanding of the bourgeois 19th century and is now fully accessible for the first-ever time. Even marginal texts that do not correspond to the classical concept of a ‘work’ have found a place in the edition. After all, the correspondence and diary entries of authors can prove to be just as important as one of their ‘major’ works.

Scholarly editions can serve to ‘ennoble’ a work. But they also have a conservative streak in that they seem to confirm and fix a list of supposedly exemplary authors. “Large-scale projects such as the Keller Edition both reflect the literary canon and also help to maintain it. That’s inevitable”, says Amrein, while adding that she believes it’s all the more vital for editors to reflect on this fact. “It’s important to make the works of well-known authors accessible in all their facets. But you can’t let yourself be seduced by false notions that you might discover unknown texts and attract attention in that way”.

She is convinced that editions should rather be focused on works that don’t have a major reputation, but that might undermine the traditional canon or expand it. Nor should we entertain overly high expectations of such editions. But “the challenges that exist can be overcome”, says Amrein.

The SNSF ceased funding new, large-scale editions as of 2021. But together with the Swiss Academy of Humanities and Social Sciences (SAHS), it continues to support projects that were already underway. This shift has not been without controversy. Some scholars in the humanities were angry and disappointed. Just over a decade ago, the SNSF was still funding not just the Keller Edition, but also, for example, the ‘Bonstettiana’ Edition that was completed in 2012, featuring the writings and letters of Karl Viktor von Bonstetten (37 volumes), plus the ongoing ‘Critical Robert Walser Edition’ (with some 50 volumes, scheduled for completion in 2032) and the ‘Historical-critical complete edition of Jeremias Gotthelf’s works’ (some seventy volumes, scheduled for completion in 2038).

Gotthelf at school

Either way, financing an edition is no easy task, not even when it comes to prestigious figures like Keller or Gotthelf. “We received funding from the SNSF, but it would never have been enough”, says Amrein. Their Keller Edition had broad support right from the outset, including from the Canton of Zurich. A great deal of effort was invested in trying to find possible sources of funding.

The Gotthelf Edition is a major project that is now primarily funded by the SAHS. The previous Gotthelf editions are not really available any more, they’re incomplete, and their text is unreliable. The new edition is being run by Christian von Zimmermann, an expert in German studies from the University of Bern. “Our project also includes Gotthelf’s correspondence. So realising it is undoubtedly a more complex task than making an edition solely of the letters” he says.

The days are long gone when articles in the cultural pages of a newspaper could trigger debates about how to best to edit the works of writers such as Friedrich Hölderlin, Georg Heym, Annette von Droste-Hülshoff and others. But von Zimmermann believes that such large-scale editions remain important: “The commentary we include enables us to ‘decentralise’ the position of the author”, he says. In their commentaries on Gotthelf’s oeuvre, von Zimmerman and his team are able to provide information on the rural underclass, Gotthelf’s domestic servants and the peasants in the countryside with little land of their own. Without them around him, Gotthelf would never have written his works in the way he did.

Von Zimmermann also believes that it is important for editions like his to be offered online in order to make them widely accessible: “A digital edition offers a great opportunity to bring literature into schools in a new form. This is why it’s important to improve how we communicate these texts, and to improve their accessibility and the options available to online users”. Members of the Gotthelf Edition staff go out visiting schools and read the texts together with the children. More than once, von Zimmermann and his team have had to acknowledge that “texts are not simply finished products”. Thanks to Gotthelf, school students are now getting directly to grips with the ideas and techniques of textual criticism.