ROBOT-INSPIRED BIOLOGY

Robotic zoology

Biology inspires robotics; robotics returns the favour. It does this by enabling discoveries that have eluded other study methods. At three EPFL labs, robots fly, walk and swim to enhance our understanding of life.

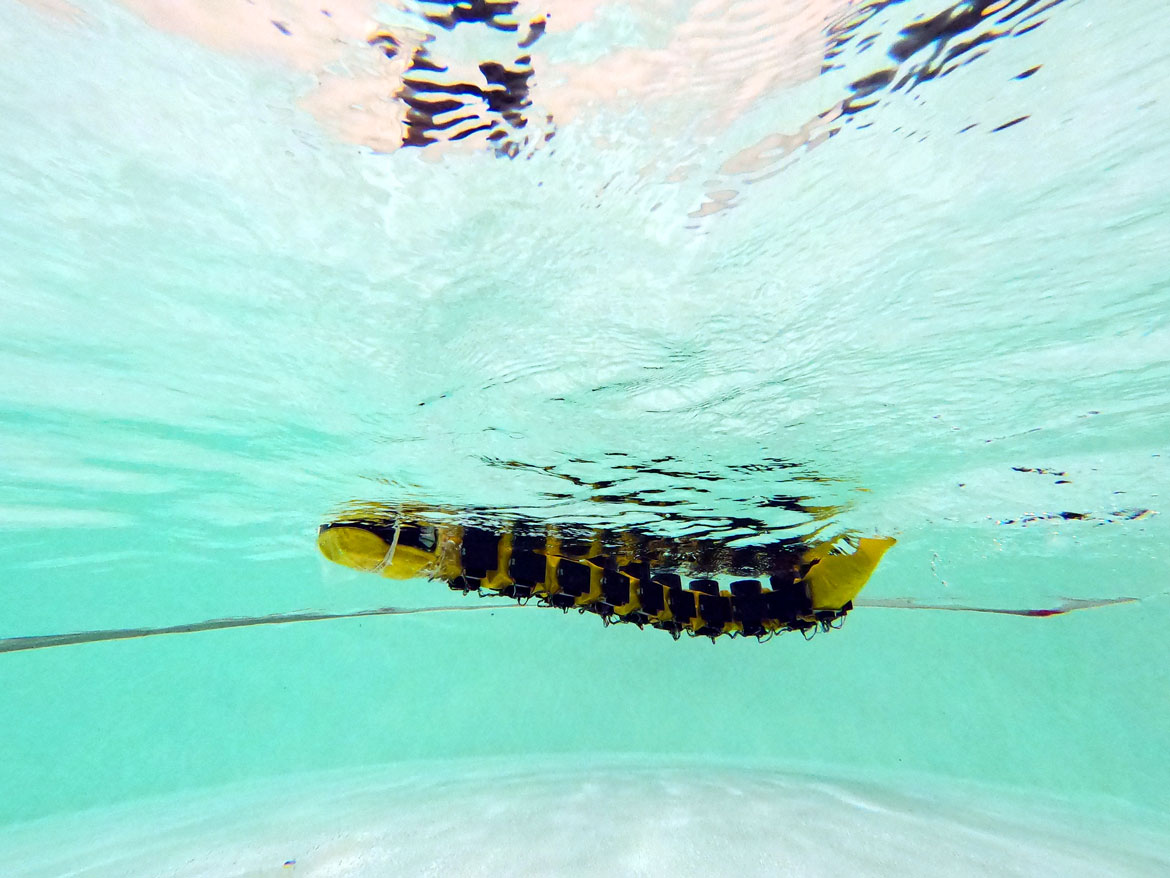

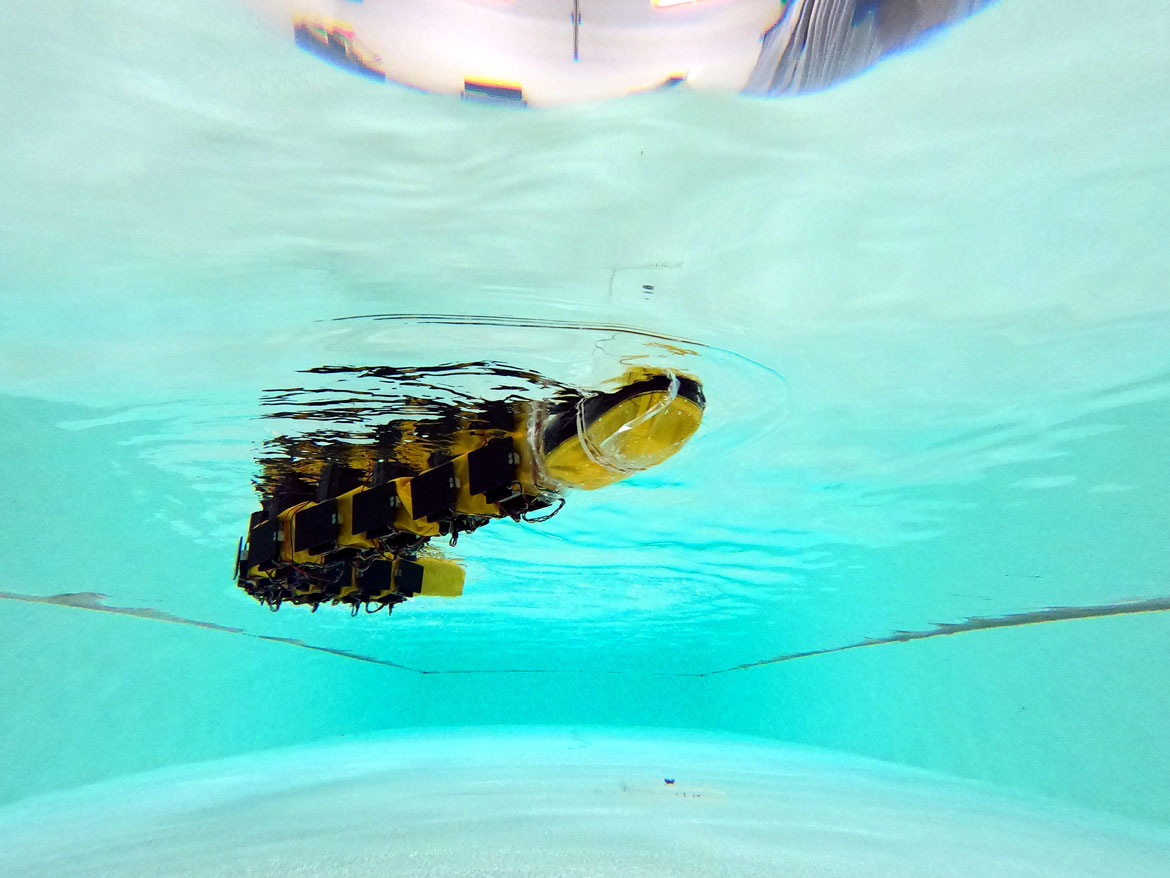

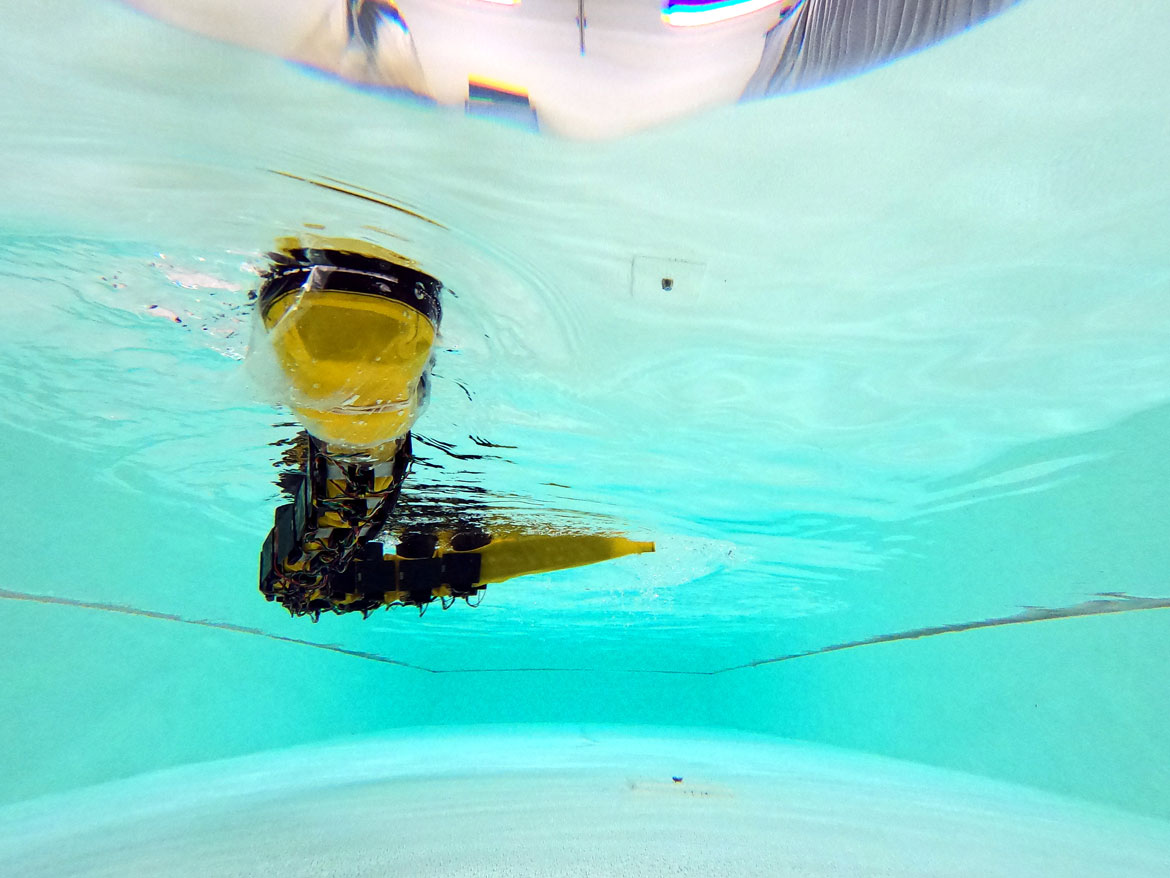

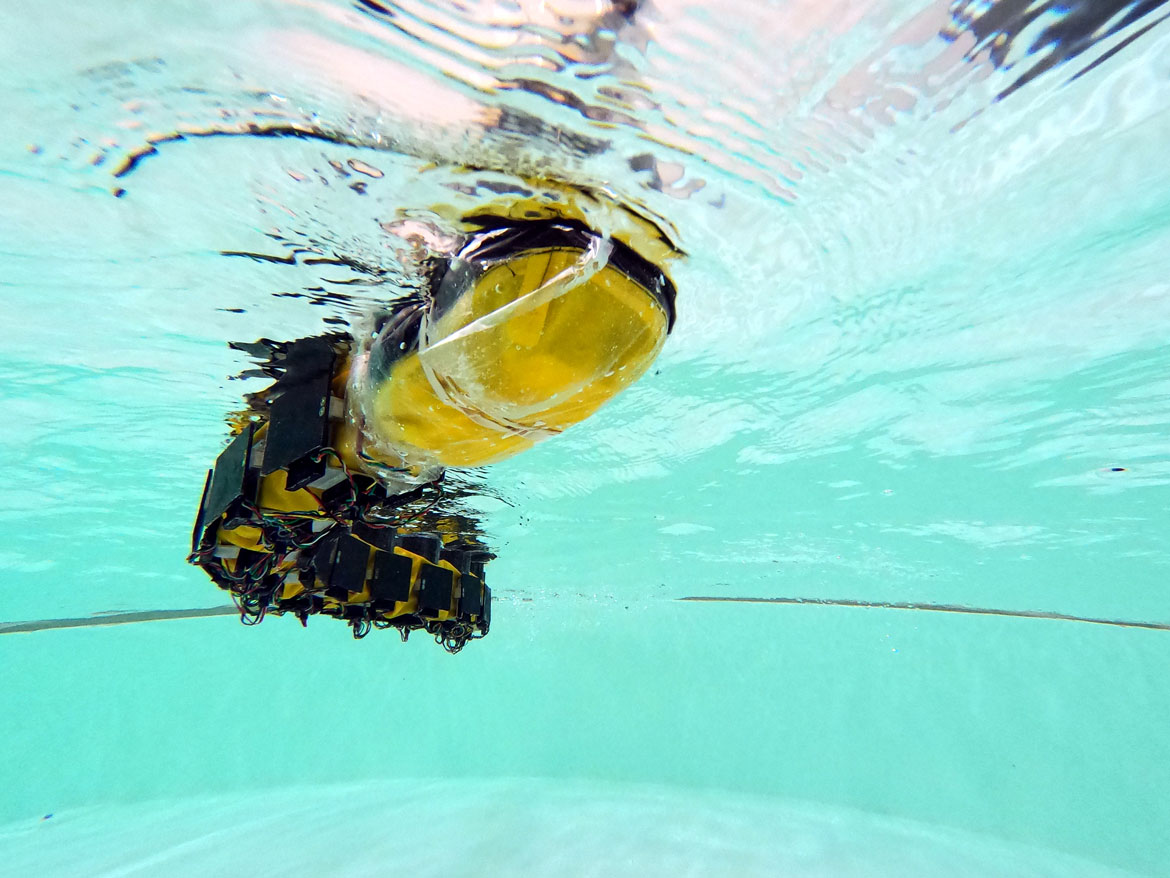

Lampreys can still swim, even after their spinal cord has been severed. Robots can explain how. | Photos: AgnathaX

Baby chickens, cockroaches, buzzards and lampreys belong to a growing taxonomy of artificial creatures inhabiting robotics labs. Most often these robots are known as ‘bio-inspired’, as they mimic nature’s tricks and improve mechanical capabilities. Sometimes, animal robotics unlocks a revolving door unveiling discoveries about the species upon which they’re modelled.

What flying robots teach us

This research field, which copies life to understand it, emerged in the 1990s and is known as ‘artificial life’. Dario Floreano was a pioneer in these exploratory studies and today he leads the EPFL Intelligent Systems Laboratory. “It was a fringe community at the time, but it was fundamental to establishing a notion that the scientific world is increasingly taking for granted, namely that robots can be used as models to tackle open problems in biology”, he says. The quantum leap in miniaturising digital tools in the early 2000s turned dreams into reality.

Over the last two decades, this approach has been adopted by four fields of study. It is now used to accelerate the reproduction of evolutionary conditions and understand the appearance of certain traits, e.g., altruism in insect societies. In the form of swarm robotics, it also assists the study of how collective intelligence emerges through sensory communication within groups. It is similarly being used to identify the role of morphology, i.e., biomechanics, in the interactions between a creature and the world. Finally, in neuronal robotics, it is being used to test hypotheses on brain function.

In Floreano’s lab, one of the latest projects has grown out of a question about the performance of drones. He is asking why drone design struggles to optimise both endurance and agility, whereas birds possess them simultaneously. Seeking inspiration in nature’s success, he has set out on a quest for data and discovered there’s actually very little knowledge about the way birds move their wings.

Floreano has turned to the work of the British zoologist Graham Taylor, one of a handful of specialists in this field. Taylor has just set out an innovative hypothesis, having observed the perching behaviour of trained buzzards. “It was previously thought that birds try to minimise the time they spend slowing down in order to land. According to Taylor’s observations, they actually minimise the time they spend in the stall angle, a position that is necessary for landing but which puts them at risk in gusts of wind”, says Floreano. “With a robotic twin of the bird, an algorithm and a wind tunnel, we were able to test and confirm the hypothesis and explain the wing and tail morphing sequence used by birds to perform this manœuvre”.

Infiltrating animal societies

Mixing with living animals, luring them by infiltrating their societies with robots, observing their collective behaviours: this is what steered Francesco Mondada – who runs the EPFL Mobile Robotic Systems Group – into biology from robotics. “To try to understand how fish interact, we can, of course, fit sensors”, he says. “But if we can integrate into their groups with an individual that we control, and then participate in their common decisions, we can go much further”.

His first project in this field dates back to the early 2000s and involved cockroaches. “That work had led us to identify the molecules and behaviours that mean insects can recognise each other”, he says. Then from 2006 he was working on PoulBot, which is based on a group of baby chickens to test the variables of their sociability. Then FishBot, as of 2013, a mini robot that swims with zebrafish, a species that was chosen because “its social communication channels were well enough known, enabling them to be implemented robotically”. This project, which was led alongside others by the French biologist Guy Théraulaz, a specialist in collective animal intelligence, opened the door to testing behavioural models on the basis of observations in live fish and to validating them experimentally.

I move, therefore I am

An ongoing project of his is looking at bees. “Up until that point”, says Mondada, “we had been working entirely in the lab: the cockroaches were in a neutral setting far from their normal environment, and the fish were in a small volume of water, because otherwise their behaviour would have resisted modelling”, he says. With bees, the project meant going into their home, if we can put it that way. But rather than slipping a robot into the hive, he simulated the presence of artificial insects “by sending stimuli in the form of vibrations and heat, which corresponds to their way of communicating, and even the famous bee dance, which we were able to influence by modifying how they recruit each other mutually to seek food”. This was done alongside a research group at the University of Graz looking at biology and the behaviour of bees, and the project led to enhanced understanding of the behaviour of the winter cluster in which bees huddle together to survive the cold.

“The ability to move is an essential aspect of who we are. From an evolutionary perspective, the development of our neural networks is linked to locomotion”. This connection between movement and cognition is one of the centres of interest of Auke Ijspeert, who heads up the EPFL Biorobotics Laboratory. For thirty years, he has focussed on it in animal locomotion, which he studies by modelling and reproducing it robotically. From eels to humans, and from birds to mammals, “vertebrates have very different modes of locomotion, but the neural networks linked to movement are surprisingly similar”, he says.

His predilection for these studies is the lamprey, a scaleless fish with a tube-like body and a striking idiosyncrasy. “If the spinal cord is cut, it continues to swim, whereas most vertebrate animals can no longer move after such a lesion”. Robotics makes it possible to run “tests that are hard to do in living animals given the practical and ethical considerations” and to investigate this phenomenon experimentally, activating and deactivating the various parts of the locomotive apparatus using a model animal. “We have thereby been able to demonstrate that the sensory feedback coming from tactile sensors on the skin suffices to coordinate swimming, even if links within the neural network are severed”, he says. Having transposed this to human bodies, results have been gained that clarify the efficacy of medical techniques to reactivate locomotion through electrical stimulation of the spinal cord.

Today, the research fields emerging from artificial life are opening up multiple new fronts. For Mondada, one objective would be for “systems to integrate life and tech so as to enable environmental monitoring, for example, gathering the signals from bees to detect instances of pollution”. For Ijspeert, the movement of an animal imitated by physical robots or by digital simulation could contribute to updating tools used in neuroscience, by highlighting the links between neural networks and the mechanical properties of creatures. In passing, Floreano says that this research “produces new scientific knowledge that drives new engineering innovation”. A virtuous circle is being plotted between so-called ‘bio-inspired’ robotics and biology that we could call ‘robo-inspired’.