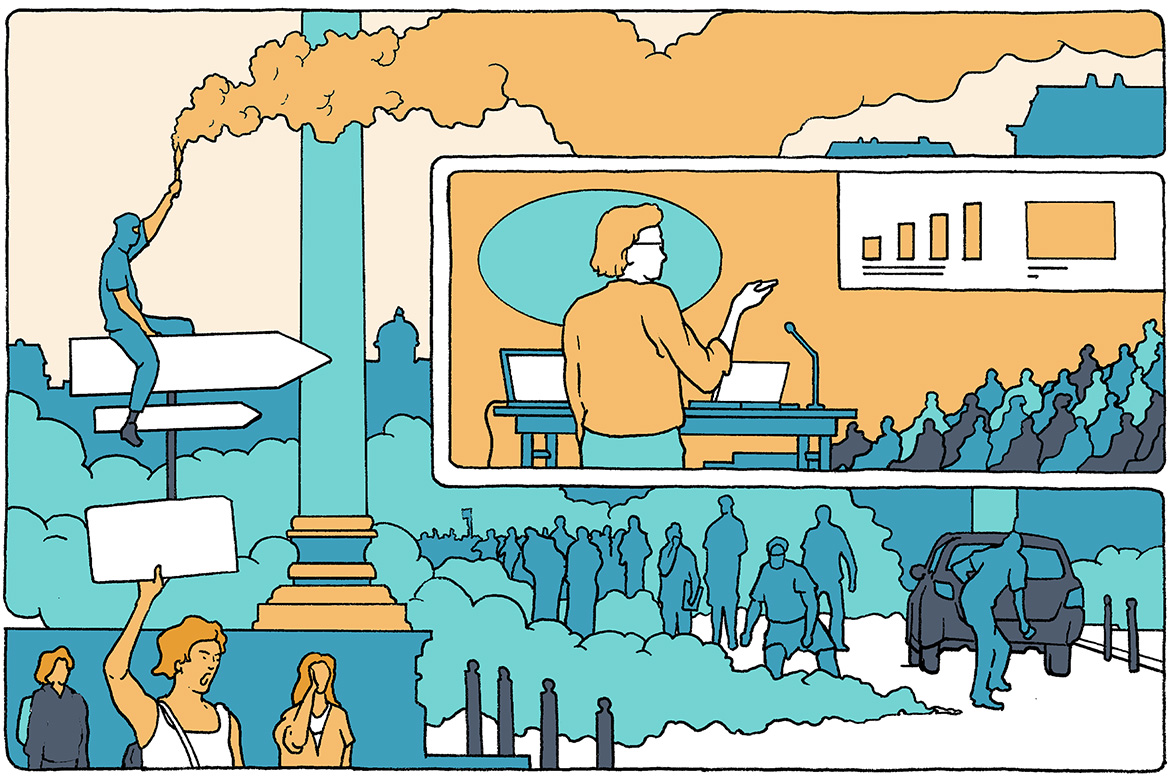

Feature: Researching for peace

Searching for a more perfect harmony

If we want to prevent war and conflict, it can help if we understand how peace can be achieved and maintained. This is the research goal of a wide range of projects that are examining all manner of processes: between different countries, different political convictions and different social strata. We take a look at six examples.

Illustration: Peter Bräm

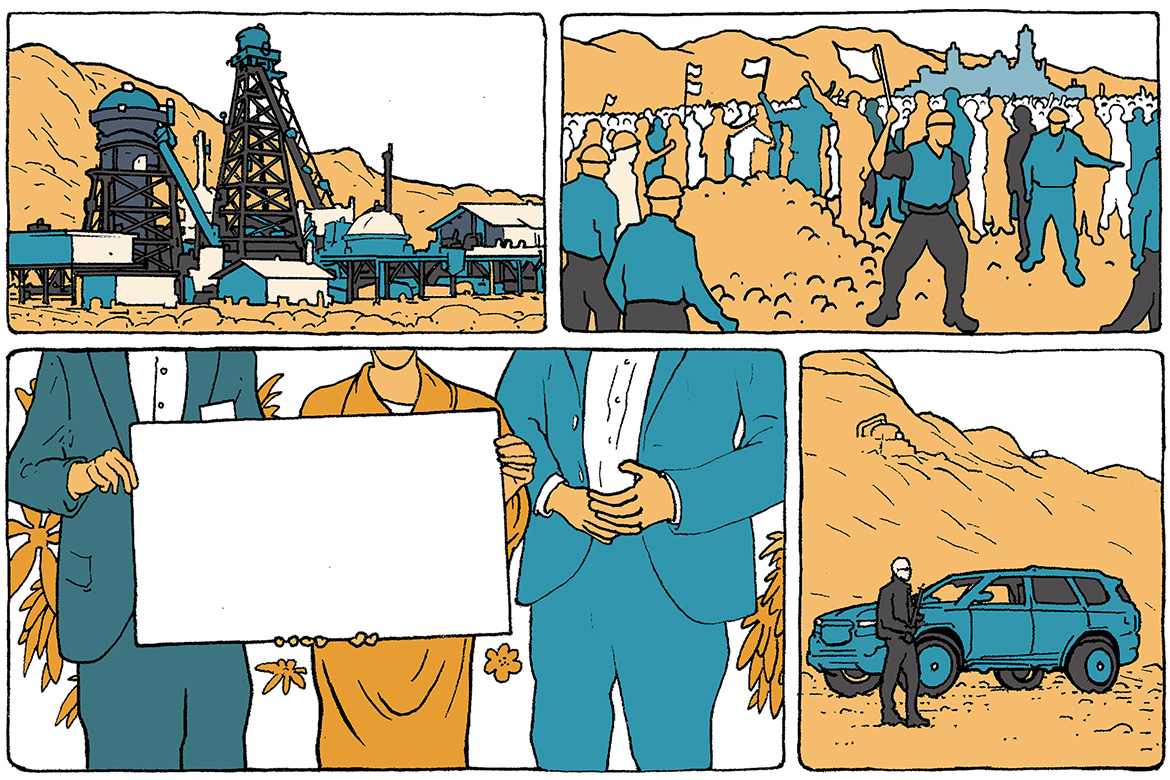

When companies have to make reparations

Companies that do business in wartime and under authoritarian regimes are often complicit in violence, either by supporting it, by profiting from it, or by actively promoting it themselves. Such misconduct and its consequences can continue to exert an impact after the end of a conflict without anyone being openly aware of it. Sometimes, such behaviour can have dramatic consequences, decades afterwards. The business ethicist Jordi Vives Gabriel at the University of St. Gallen wants to understand whether companies are willing to deal with past transgressions, and if so, how they do it. To this end he has been focusing on the 2012 Marikana massacre in South Africa in which 34 striking miners were killed by the police.

The miners killed were employed by the mining company Lonmin – which today goes by the name of Sibanye-Stillwater – and it has since initiated various forms of material and symbolic reparation. It has provided apartments for the men’s widows and scholarships for their children, and has also held annual commemorations and erected a memorial wall. “But even initiatives with the best intentions cannot undo the suffering”, observes Vives Gabriel. He believes that companies sometimes view claims by victims far too much through the lens of predetermined processes, and that they don’t listen properly to what people are actually saying.

Vives Gabriel has conducted dozens of interviews, extensive archival work and field research too. One thing has become particularly clear to him: “If massacres like the one in Marikana are to be prevented in the future, then people have to address the underlying dynamics seriously”. Despite the democratisation process in South Africa and the emblematic work of people like Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu, many of the social and economic conditions that were typical of the apartheid regime have persisted to this day. This is especially the case in sectors such as mining. Poor wages and substandard housing are still common there, and excessive police violence remains tolerated. “It was precisely this legacy of apartheid that led to the strike and the massacre in Marikana”.

Illustration: Peter Bräm

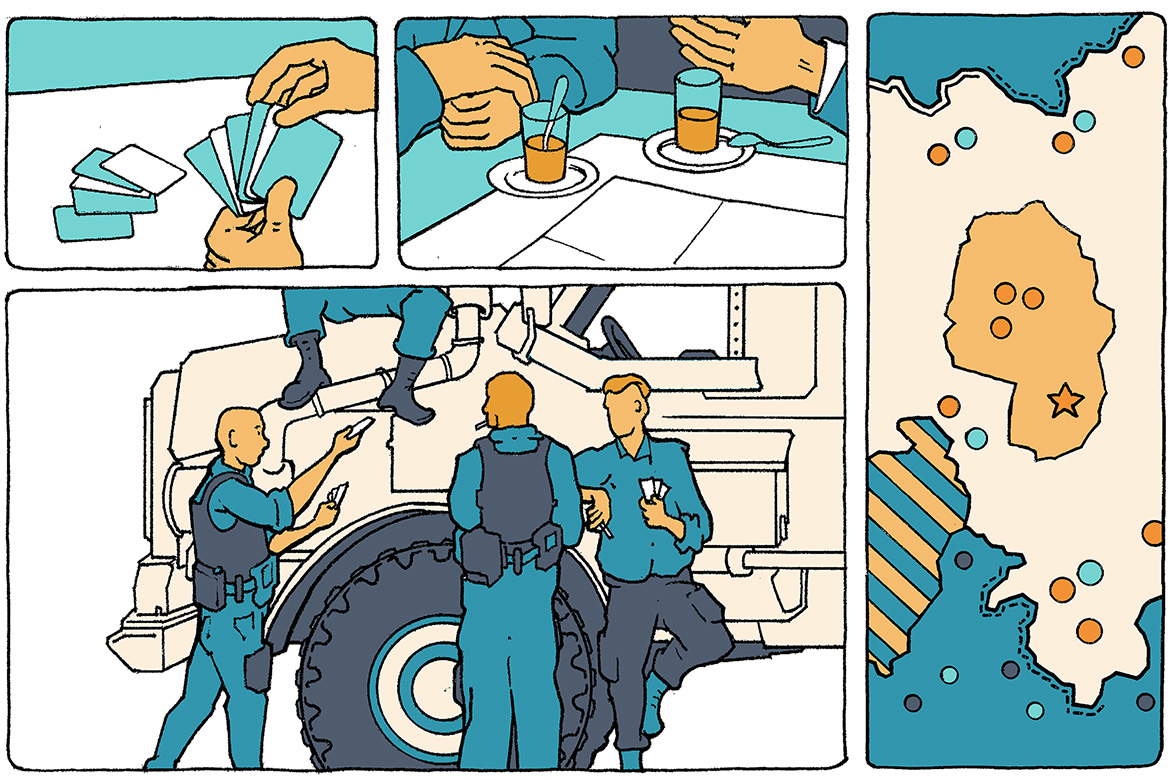

How the UN and local troops can work together

Peacekeeping missions conducted as a partnership between United Nations troops and regional actors are the norm today. “Nevertheless, there has been little research into their effectiveness to date”, says Corinne Bara, a political scientist at ETH Zurich. What’s more, she adds, the focus is mainly on the problems and challenges involved. But since the UN is increasingly outsourcing responsibility to regional troops or state missions, Bara and her doctoral student Maurice Schumann have been asking: Would it be better for the UN to go it alone instead? Are there good reasons to undertake parallel peacekeeping operations? To find out the answers, Bara and Schumann decided to investigate the number of combat-related deaths in such instances. “Of course, fewer deaths in the field don’t signify peace”, says Bara. Some employees of the UN have also criticised them for using such a narrow criterion for success. But they are convinced that only assessing a standard military measure such as this will enable them to undertake comparisons with previous studies.

Bara and Schumann have concluded that UN peacekeeping missions are able to contain violence in combat situations even when they operate alone. But if the Blue Helmets are supported by regional partners, they can achieve this same goal with fewer troops. The reason for this, believe Bara and Schumann, is that while local units are actively involved in combat, the UN is freed up to employ its broad toolbox of options, from securing buffer zones to organising elections and protecting aid convoys.

To their surprise, Bara and Schumann found that that non-UN forces tend to cause more deaths when left to their own devices. No one expects the military to provide a permanent resolution to conflict, says Bara. “But these peace missions even fail their core task”. Military strategies only seem to work when they are embedded in a political search for a solution and in the work undertaken by the UN. Bara sees this conclusion as a reason for the UN not to withdraw from peace missions prematurely. Regional partners can provide important support for the UN, she says, but are no substitute for it.

Illustration: Peter Bräm

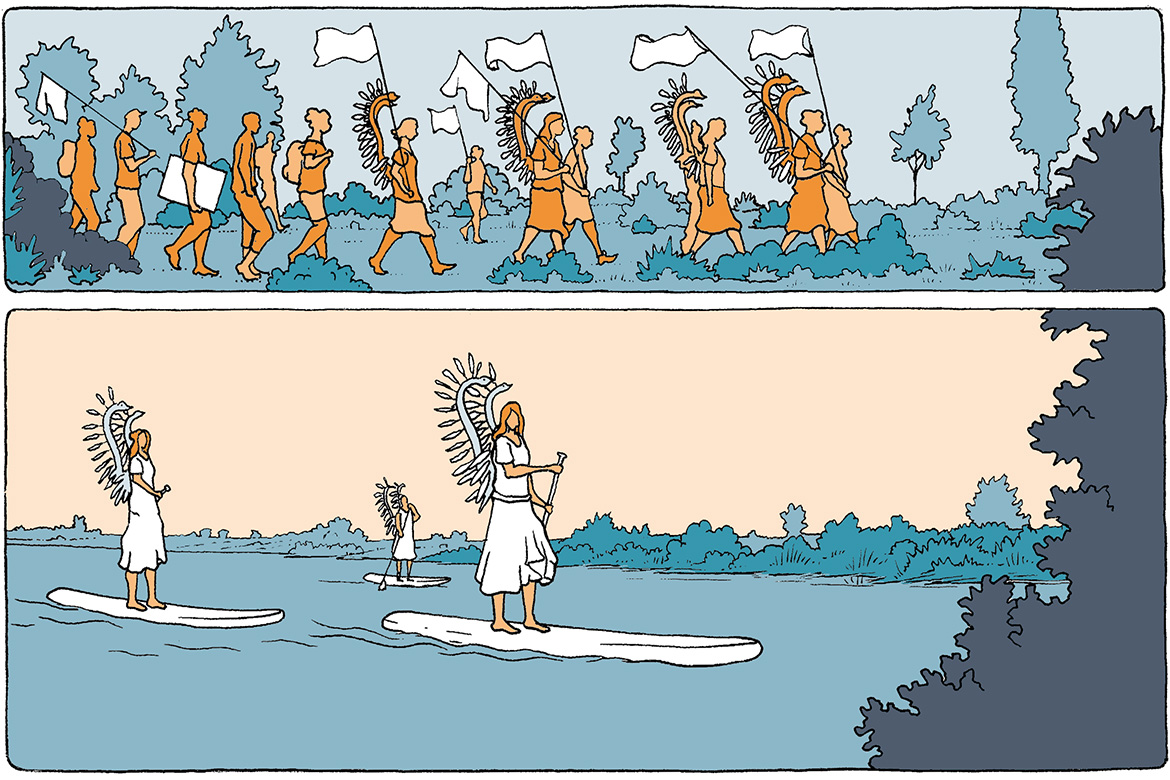

Using performances and cycling tours to reduce conflict

Art and popular culture can also help to promote peacebuilding and prevent conflict, according to the art historian Jörg Scheller and his team. They offer the example of the environmental activist Cecylia Malik from Cracow in Poland, who has used her performances to various ends, including campaigning against the straightening of a river because it could eventually lead to a natural disaster that might in turn result in violent conflict over resources. But does this really count as conflict prevention? “Recent research has taken a very broad view of peacebuilding”, says Scheller. But at the same time, he adds, such actions are themselves also a benchmark for peace preservation. “When people can openly address conflicts and criticise them, then things are generally more peaceful there than elsewhere”.

Scheller’s research in Poland is mainly based on interviews and documentation. By contrast, the doctoral student Rada Leu is a participating observer in the Oberliht artists’ group in Chisinau in Moldova, who operate against the backdrop of the frozen conflict between the Republic of Moldova and Transnistria. The group has been working to empower civil society since the 2000s. It helped to found the first ‘queer café’ in the country and has organised bicycle tours along the River Dniester where the hostile parties were able to get to know each other better.

Armenia and Azerbaijan have been engaged in an armed conflict over the region of Nagorno-Karabakh. In the Armenian capital city of Yerevan, the researcher Rana Yazaji has been busy setting up a space for art and culture in which displaced persons from the disputed region can play a hosting role. She has been both reflecting on these processes and documenting them at the same time.

“Many of these projects are notable for their long-term horizons”, says Scheller. He is convinced that this is the only way to achieve the non-violent transformation of conflict and a sustainable peace. Such a process cannot simply be stipulated by a contract, as it needs aesthetic formats and independent spaces and is closely linked to art and culture. “It has to be lived”, he says.

Illustration: Peter Bräm

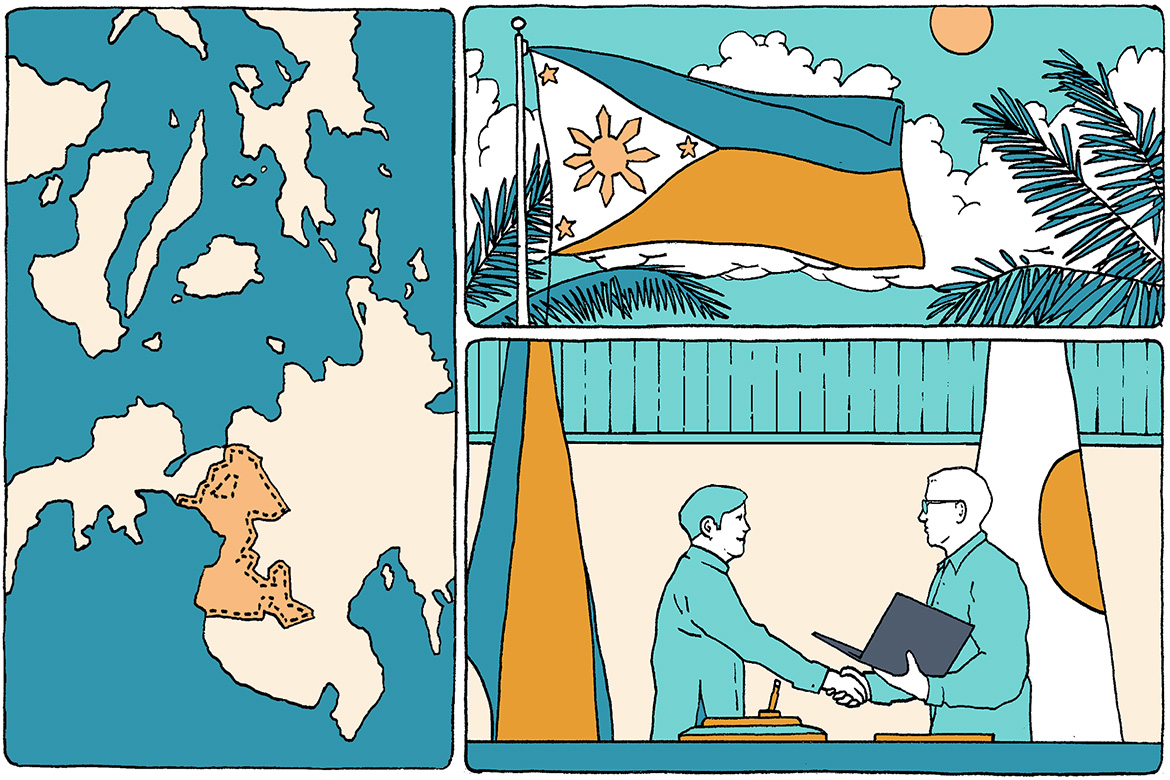

How China, Japan and Russia bring peace

For several years now, countries such as China, Japan and Russia have also been having an impact on global peace and have been challenging Western, liberal ideas about human rights and democracy. In four case studies, the political scientist Keith Krause and his team from the Geneva Graduate Institute have been examining how these new actors in peacebuilding engage with local leaders, and how their norms have become embedded in their work.

To do this, however, researchers first have to bid farewell to their binary understanding of things, says Krause. “Dividing up the world into Western and non-Western peacebuilding measures is far too limiting”. Japan is a prime example of this. Its government works closely with Western organisations and in many respects has embraced their liberal agenda as its own. But at the same time, it remains cautious on issues such as civil society or gender norms, even though it rarely openly rejects them, says Krause. Japan is also setting itself apart from China, such as when it comes to the Chinese belief that peace is achieved by promoting infrastructure projects.

Krause and his team monitor the work of these new protagonists in the places where their programmes are actually being implemented. They are interested in how local leaders experience the resultant exchange. Do they see themselves only as recipients, or are they actively helping to shape these peace programmes? What, for them, constitutes good cooperation? Krause has found that locals on the Philippine island of Mindanao, for example, trust Japanese envoys more than they do the representatives of the UN. The West is perceived as being less reliable due to frequent changes in contact people on the ground, whereas envoys from Japan cultivate more binding relationships and remain for longer in their posts. “The aim of our research is also to hold up a mirror to the liberal peacebuilding bubble”, says Krause. He is convinced that it’s time for us to pose more critical questions of our own ideas and practices and to think in broader terms about peacebuilding.

Illustration: Peter Bräm

Understanding violence in the banlieues

Research into peace and conflict is concentrated in universities in the Global North, though most of the conflicts studied there are situated in the Global South. The sociologist Claske Dijkema admits that it took a long time for her to question this tendency. She became aware of it during the weeks of riots that took place in France in the mid-2000s. She was conducting research in South Africa at the time, and her colleagues there realised before she did that their scholarly tools could also be applied to instances of social unrest like in the banlieues. “We in Europe, on the other hand, still like to cling to the idea that wars only take place elsewhere – even if the war in Ukraine has rather shaken up this image”.

Ever since then, Dijkema has been trying to break away from this view of conflict. She is also focusing on protagonists in civil society who are committed to social justice in cities across Europe. For example, she spent several years monitoring the work of the collective Agir pour la Paix (‘Acting for peace’) in Grenoble. This is an association that was founded in 2012 by the friends and relatives of two young people from a marginalised district of the city who were brutally murdered. The association’s peace-building activities include regular workshops and study trips. Dijkema’s research is concentrated primarily on the collective peace discourse. When young people are justifiably angry and in despair, how can words help them to be seen and heard as fully-fledged, committed citizens?

This is naturally a very localised form of peace research, says Dijkema. But her main goal is to show how the knowledge gained from research into peace and conflict can be applied more broadly. “It’s not about equating unrest with war”, she says. But just because there isn’t a war going on doesn’t necessarily mean that there is peace. “Unrest and everyday life often take place at the same time and in close geographical proximity to each other. The consequences of violence are also often similar in that they trigger fears for one’s own physical safety, for example, or prompt people to withdraw from public life.

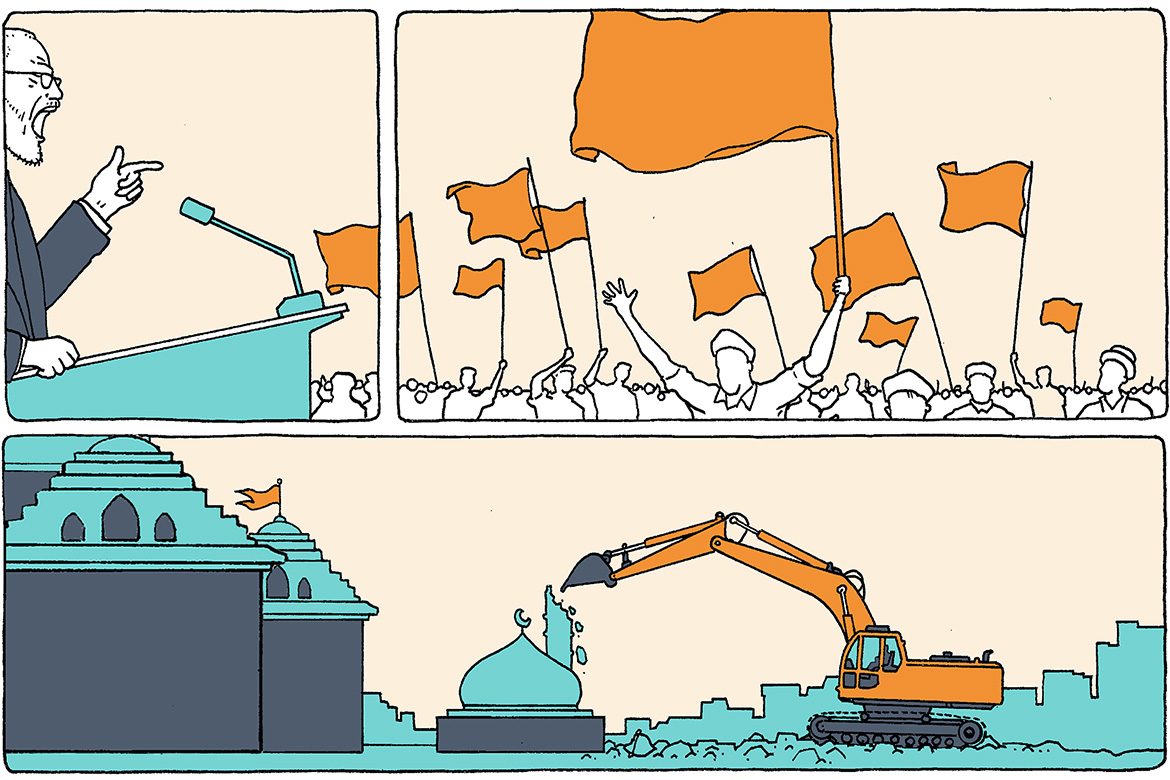

Illustration: Peter Bräm

When an extreme majority determines policy

Since the rise of populist heads of state such as Vladimir Putin and Recep Erdoğan and extremist movements such as the Hindu nationalists in India, urgent questions have been asked about how such majority nationalist ideologies – which demand the political dominance of specific ethnic, cultural groups – actually influence violent conflict or even civil war. For far too long, says Lars-Erik Cederman, a conflict researcher at ETH Zurich, we have been focusing exclusively on the impact of minority resentments on social peace.

Together with the postdoc Andreas Juon, Cederman has set up a global dataset to monitor such movements from roughly 90 countries since World War II. This dataset includes claims regarding minority groups and information on whether these organisations have been in government. One example is the Bharatiya Janata Party of India’s Prime Minister Modi, which in recent years has increasingly curtailed the civil rights of Muslims and legitimised violence against them.

Then there is Spain’s Vox, founded in 2013, which rejects the claims to autonomy of the Basque and Catalan minorities. Juon explains that he and Cederman will be linking statistical evaluations with case-specific analyses. On the basis of past events, such as the human rights violations against the Rohingya in Myanmar, their aim is to examine whether the correlations that they calculate in fact correspond to the real role that majority nationalist movements have played.

Cederman and Juon also hope to find answers about how escalation can be prevented. Power-sharing between an ethnic majority and a minority, as is currently happening in Bosnia and Burundi, is a controversial process and can even lead to yet deeper political divides, says Juon. But in the long term, it can also lead to a situation where it’s not just the elite that have a greater understanding for the concerns of the minority, but the broader populace too. What’s more, says Juon, “when nationalist parties are part of such coalition governments, their members are compelled to abandon their most extreme demands”.