PORTRAIT

Excited by genetics, concerned about ethics

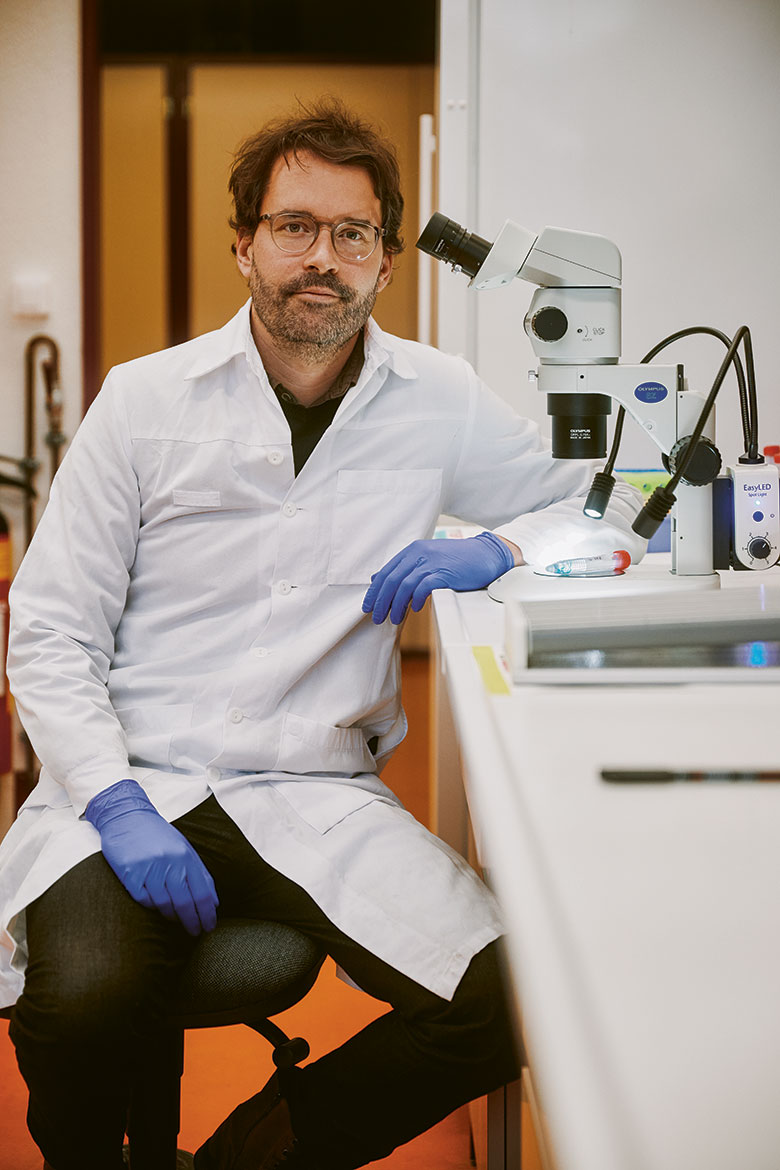

Guillaume Andrey studies embryonic development and deformity. He has also been recognised for his efforts to reduce the number of mice sacrificed in the name of science.

Guillaume Andrey loves genetics because it’s so logical. And he wants to spare the lives of as many lab mice as possible. | Photo: Anoush Abrar

“There’s a higher purpose”. Guillaume Andrey often repeats this phrase to himself when he has to euthanise a mouse in the context of his research. “For most scientists, including myself, animal experimentation is not a part of our pleasure”. He’s an associate professor at the Department of Genetic Medicine and Development at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and warns that ‘higher purpose’ doesn’t rhyme with ‘free pass’. According to Andrey, who’s originally from Valais, everything that can contribute to reducing the number of animals sacrificed in the name of science should be tried.

When he launched his own research group in 2018, Andrey didn’t hesitate to put his money where his mouth was. He dedicated part of his time and energy to setting up a protocol allowing him to reduce by about 80 percent the number of mice needed for his work on molecular processes controlling gene expression during embryonic development. In collaboration with the Unige Transgenesis Platform, Andrey (42) adapted a method called tetraploid aggregation. It allows him to obtain embryos directly with a specific genetic configuration from modified stem cells in the laboratory and stored in liquid nitrogen.

“When we need them, we thaw them out”, which avoids having to establish and maintain entire lines of living mice. As for the embryos receiving these cells, they are recycled from experiments conducted in other laboratories. “Only the female carriers where we transfer the embryos must be sacrificed.”

Andrey’s efforts alongside those of his team were crowned with the 3Rs award in 2023 by the Swiss 3R Competence Centre. This prize honours work that significantly advances the principle of the 3Rs, which means replacing animal testing whenever possible, reducing the number of animals used if replacement is not possible, and refining the conditions of those used.

A bridge between the visible and the invisible

When Andrey receives us at the end of the day in the heart of the complex site of the University Hospital in Geneva (HUG), he begins by asking us to excuse his state of fatigue. Between signing off several scientific publications, applying for European funding, and caring for his two young children, he’s “been burning the candle at both ends”, he says with a wink. This doesn’t stop him from taking the time to show us around his fully equipped laboratory and introduce us to the members of his research group, consisting of eight people in total. Nor does it prevent him from patiently answering our questions, clearly making an effort to explain complex concepts in simple terms. Both his parents were educators by training and he’s obviously inherited their teaching genes.

“I didn’t choose the most straightforward discipline to explain to the general public”, he says. And yet, “the irresistibly logical aspect of genetics confers a form of simplicity on it”. As a personal preference, he also appreciates “what’s logical and predictable”. He pauses, thinks, and comments with a laugh: “When I put it that way, people think I’m a bit rigid of mind; what I want to say is that when something doesn’t go as planned, I like to be able to trace back why”. And rightly so: genetics “allows us to obtain clear and precise answers, without grey areas”.

But what really blew his mind when he discovered this discipline during his biology studies at the University of Geneva was that “genetics creates a bridge between something completely invisible, namely the genome, and the visible and tangible reality of skin and limbs”. In turn, it seems to “give meaning to the world around us”.

More clown than class pet

Once caught in the web of genetics, Andrey never managed to extricate himself from it. As an adolescent, he wasn’t exactly a model student – “I was more of the type who used the chemistry kit I received as a gift to blow things up and make my two younger brothers laugh” – and yet, he found himself putting his nose to the grindstone. In 2006, he landed a spot in the NCCR ‘Frontiers in Genetics’, which allows PhD students and researchers to spend several months in different labs across the country. In Zurich, he worked on drosophila; in Basel, he studied retinal development; and in Lausanne, he researched specific viruses.

For his thesis at EPFL, he decided to focus on limb development in mice. His research results showed that the mechanism governing ankle formation is recorded in the genome structure. This discovery helped open doors to several prestigious international research institutes for him. At the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin, for example, Andrey chose to set up his microscope as a postdoc to work on skeletal development.

The year 2018 marked Andrey’s return to Switzerland and the University of Geneva, where he set up a laboratory aimed at understanding how the genome controls gene activity during embryonic development. “To build a given structure, for example, a limb, the genome must find a way to activate the right gene in the right place and at the right time; if an error occurs when the genome gives its orders, deformities can occur”.

The mysteries of clubfoot

During its first six years of activity, Andrey’s team made several discoveries that garnered significant media attention. One study focused on a gene involved in lower limb formation – Pitx1 – and showed, for example, that even a small perturbation in the activation process of this gene can lead to clubfoot, one of the most common leg deformities.

Geneva loop

Guillaume Andrey is an associate professor at the Department of Genetic Medicine and Development, Faculty of Medicine at the University of Geneva (UNIGE). Born in Sion in 1982, he studied biology at UNIGE before joining the laboratory of geneticist Denis Duboule, then affiliated with the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), while working on his doctoral thesis. After a postdoctoral stay at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin, Andrey returned to UNIGE in 2018. He created a laboratory dedicated to studying the molecular processes that control gene expression during embryonic development. Andrey lives in Geneva with his partner and their two children.

In June 2024, the laboratory published the results of a study focused on the regulatory regions of gene activity in chondrocytes, the cells at the base of long bone formation during development. “We made a simple observation: variations in these regions directly affect the construction of our skeleton, and therefore our height”.

Even fewer mice

By the end of 2024, Andrey had secured a new grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation that will allow his laboratory to continue its activities. “We particularly hope to deepen our research on the trajectory of gene regulation during limb development”. This will involve, for example, observing whether gene activity can experience transient variations and, if so, what impact such variations would have, even if they are short-lived. Instead of focusing on a specific moment in embryonic development, team members will monitor the entire process.

In parallel with these research efforts, Andrey will continue to explore ways to reduce – even further – the number of mice required for laboratory operations. “The ideal would be to find a way to completely eliminate the need for surrogate mothers, but we’re not there yet”. The case may arise: “If I create an embryo without using a surrogate mother, what will the child’s status be?”