Lithium

Lithium: One of the most mysterious elements in space and on Earth

It’s still a mystery how lithium came to be on Earth at all. When it’s mined, it causes pollution and conflict; and when it’s used, it’s difficult to tame. We look at the facts of lithium, the recalcitrant key resource for the energy transition.

In this basin in the province of Catamarca in Argentina, brine is evaporating in order for lithium to be extracted from it. | Photo: Anita Pouchard Serra

The story of what’s at present just about the most sought-after element in the world began in the first five minutes after the Big Bang, some 13.8 billion years ago. It was back then that the lightest metal in the universe came to be: lithium. But no one knows exactly how this key resource for our energy transition actually arrived on Earth in the first place. Lithium was first discovered around 200 years ago, in the Utö mine to the south of Stockholm. This metal cannot have originated on the Earth itself, because creating it requires the kind of massive energy that only occurs in outer space and inside stars.

“Lithium is one of the most mysterious elements in the Universe”, says Anna Frebel, an astrophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) who is an expert on old stars and on the early phase of the Universe. In its pure form, this element is extremely reactive. The high core temperatures of even the earliest stars almost burnt it away completely. But all the same, according to the standard model that describes how the Universe was formed, significantly more lithium ought to exist in the Universe today. Our measurements have proven that the magnitude of hydrogen and helium that exists in the Universe is roughly what we would expect. But lithium exists in somewhere between a quarter and a half of the amount that has been predicted. Why is that? “We don’t know”, says Frebel. It’s called the ‘cosmological lithium problem’.

Just a cosmic accident

The problems begin with how to detect it in the first place. Unlike hydrogen and helium, lithium cannot be measured in the gas clouds of galaxies. Astronomers can only observe it from Earth on the surface of specific types of stars. But these signals tend to be weak. There are a few exceptions, however. Frebel has been collaborating with Corinne Charbonnel of the University of Geneva, and together they recently detected a thousand times more lithium in the star J0524-0336 than in comparable stars.

It’s a stroke of luck, but puzzling. Charbonnel has published an article in which she states that it could be due to a unique process in the course of the star’s existence. According to this theory, lithium must have been produced for a short time – roughly a thousand years. That would be like the blink of an eye in the life of a star that’s existed for billions of years. After that, it would burn up the metal completely.

“Unlike with other elements, there was no real production of lithium after the Big Bang”, says Frebel. “Its formation seems more to be a kind of cosmic accident”. We are able to determine with some precision how many other elements were formed that exist on Earth. Iron comes from supernova explosions, gold from neutron stars colliding, barium from a certain class of old, giant star.

“But lithium, in comparison, is like a slippery fish”, says Frebel. There is one hypothesis, however, according to which lithium was produced by a phenomenon that researchers call ‘spallation’. This is when high-energy particles making their way across the Universe randomly hit heavier elements that then decay, creating lithium. This would mean that lithium could have been formed again and again, while its lack of reaction partners would have enabled it to remain stable in the endless expanses of the Universe.

A big opportunity or a big destroyer

But even here, the question remains as to how lithium reached the Earth. Frebel shrugs her shoulders. “We don’t know that either”, she says. When the Earth was formed from a cloud of gas and dust it must already have contained the lithium that we use in batteries today. It must have sunk down into deeper layers as the Earth solidified and was mostly bound as salts. Certain geological conditions are needed to bring it closer to the surface again. This is why it can only be mined in a few places, with just six nations – Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Australia, China and the USA – having some 70 percent of all known lithium reserves. “It’s not that easy to get hold of this valuable raw material”, says Marc Hufty, a development researcher at the Geneva Graduate Institute, who has been investigating the problems of lithium mining in South America.

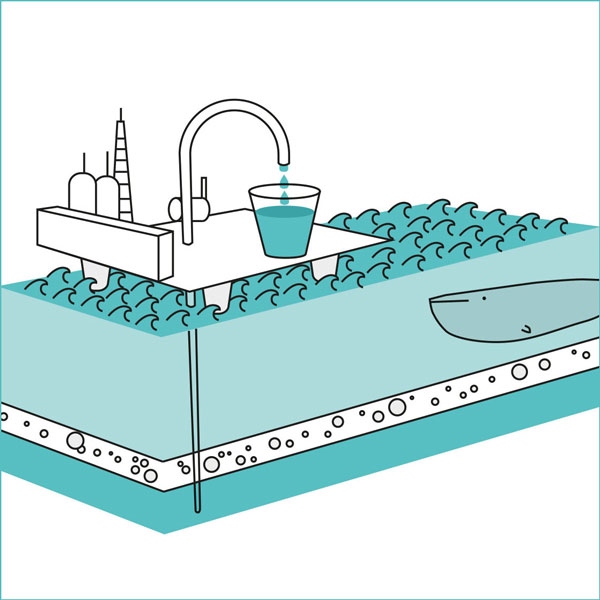

There are two methods for mining it. The first means extracting it from hard rock using conventional mining methods and heavy equipment, as is practised in Australia, the world’s market leader in lithium production. Often, around one tonne of granite has to be crushed to get a single kilo of lithium. It also has to be washed out using chemicals – some of which are highly aggressive. The second method – employed primarily in Chile, Argentina and China – is to extract lithium from salt flats, pumping brine out of the salt crust and concentrating it in huge basins where the water is evaporated in the sun. “Both processes are very resource-intensive”, says Hufty, requiring a lot of energy and large quantities of water: “They also generate a lot of waste, dust, acids, chemical by-products and contaminated water”. Extracting lithium often sparks resistance, such as in the Altiplano, the high plateau of the Andes, where local residents know it usually results in the large-scale destruction of unspoilt landscapes and of land otherwise used only for subsistence farming.

Lithium extraction is bringing about far-reaching social changes in those areas. Local communities are divided. Some accept mining as a source of income, licensing fees and jobs, while others reject it, because it destroys the environment and is altering traditional ways of life. “These fractures are often intergenerational, as younger people are attracted by the new consumer opportunities”, says Hufty. “Lithium has great symbolic significance in Latin America, just as it used to be the case with oil. It offers an opportunity to jump on the bandwagon of industrial growth at last”. But this hope is often not realised.

At the same time, global demand is increasing. Lithium is very light and emits electrons quickly, which is a big advantage when you want to store electricity – such as in rechargeable batteries. So-called lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries are currently the dominant storage technology on the market. We find them in smartphones, laptops and electric cars. Lithium ions flow between the anode and the cathode, and they have the advantage that the flow of current is not dependent on chemical reactions that decompose the electrodes.

The race for the best ion battery

The foundations for the development of the lithium-ion battery were laid during the oil crisis of the 1970s. It was based on the ideas of three researchers who in 2019 won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. But this material is not easy to tame. Battery fires occasionally occur, which merely demonstrates how important it is to tame the element’s reactivity. It reacts so quickly with water or oxygen that it almost never occurs in its pure, metallic form in Nature. If you were to throw a lump of lithium into water, it would zip back and forth, fizzing, and ignite itself.

In order to make modern high-performance batteries stable, researchers have to employ all kinds of tricks. For example, they can build up the batteries in layers so that the lithium is repeatedly isolated spatially. The chemical reactions in a battery also have to proceed in a highly controlled manner so that the energy released during discharge can be tapped in a focused way. Ali Coskun is a chemist at the University of Fribourg who is researching into new types of batteries together with his colleague Patrick Fritz. There are promising candidates that combine lithium and sulphur as the materials for electrodes. “One major advantage of this is that sulphur is more easily obtainable”, he says. Sulphuric acid or elemental sulphur can be produced very easily on an industrial scale. The second advantage is that batteries with lithium-sulphur cells are up to 40 percent lighter than Li-ion batteries – and even up to 60 percent lighter than the lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries that are also in common use.

The problem is that the reactions are still very slow in some cases. Coskun and Fritz are therefore engaged in basic research and are currently focussing their hopes on a new type of electrolyte. That’s the material located between the anode and cathode in a battery. They are preparing a scientific paper on it, and an industrial partner of theirs in South Korea will soon be testing their new batteries. “But it will still take five to ten years for it to become market-ready”, says Coskun, who emphasises that everything about these batteries is a race. “Chinese companies already dominate battery production across the world, and nine out of ten publications in basic research now also come from China”, says Coskun. Europe’s only chance, he insists, is to become even more innovative – which is why it’s all the more important for nation states or the EU to sponsor basic research, for example. Despite all the mysteries surrounding the origins of lithium and the challenges involved in mining and taming it, it will remain the crucial element of the energy transition for the near future.