Tinnitus

Mental training for the ear

People suffering from tinnitus constantly hear phantom noises that have a negative impact on their everyday lives. Swiss researchers are now investigating whether those affected can use neurofeedback to mitigate it.

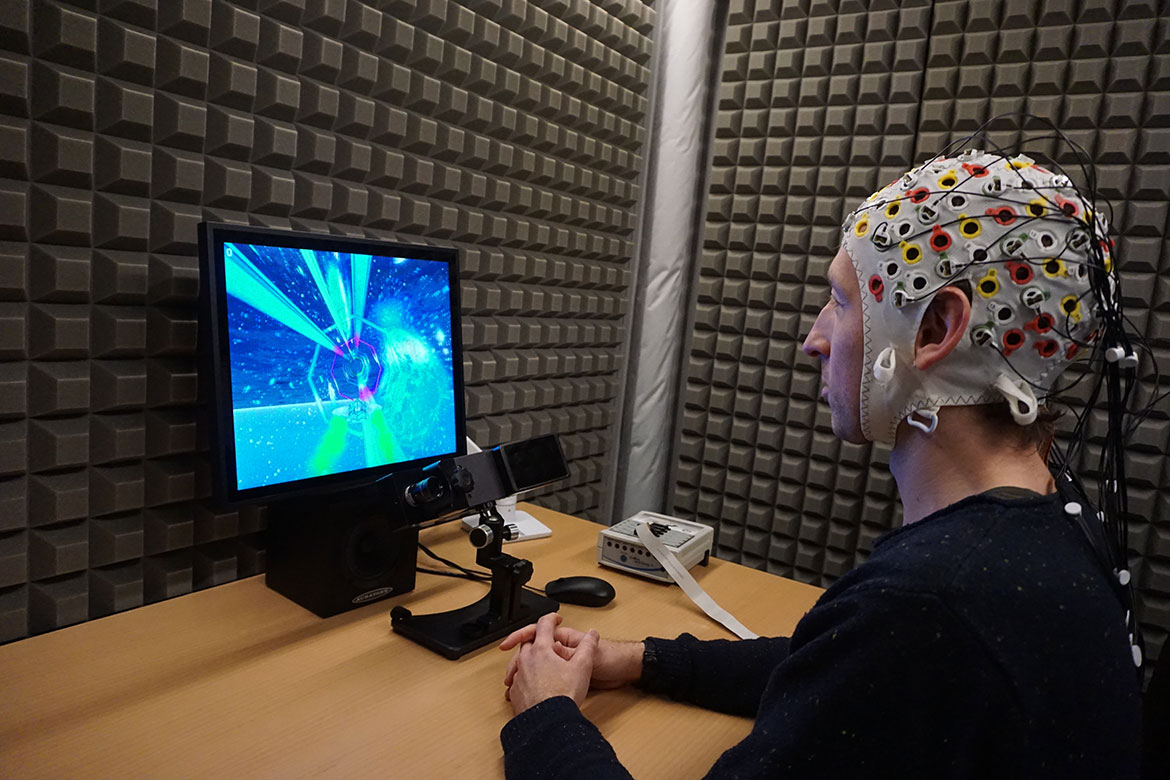

Here, a patient is learning to regulate the activities of his cerebral cortex using neurofeedback. This could help him to deal with the phantom sounds caused by tinnitus. | Photo: Provided by subject

People with tinnitus complain of a long list of phantom sounds in their head, from ringing to buzzing, whistling or hissing. But the underlying phenomenon is always the same: they hear a continuous sound in their ear that has no external acoustic source, because it’s produced by the brain itself. These noises are a mystery to medical science because they take so many different forms and can have just as many different causes.

In most cases, tinnitus is temporary – it can occur, for example, after one has heard a loud bang. But it can also be caused by medication, stress, head trauma, infections or progressive hearing loss. “According to one of the most common theories, the brain compensates for a loss of hearing by means of a false adjustment, creating the sensation of a sound even though there is no external source for it”, says Dimitrios Daskalou, a tinnitus researcher at the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG).

Moving an object on a screen with your mind

Tinnitus will affect up to one in five people at least once in their lifetime. In Switzerland, roughly one in 50 will suffer from its chronic form – which in medical terms, says Daskalou, means that its symptoms last for longer than six months. It can often have a severe impact on one’s quality of life. More than a third of those with tinnitus suffer from depression, sleep disorders or anxiety. The current standard treatment for it is cognitive behavioural therapy, whose primary goal is to teach people how to live with it. But tinnitus varies greatly in how it affects people, and is often not permanent.

Recent years have seen the launch of a number of projects that rely instead on so-called neurofeedback. This type of therapy is based on two assumptions: first that the human brain is capable of learning, secondly that tinnitus causes a measurable change in brain activity among those suffering from it. “Using neurofeedback, people themselves can learn to control the activity of a specific region of the brain”, says Basil Preisig of the Institute of Comparative Linguistics at the University of Zurich.

“We are testing whether the misdirected brain functions that are the cause of tinnitus can be corrected in this way”. He is currently heading a project investigating our ability to listen in acoustically difficult situations. “Being able to focus on a speech signal while blocking out background noise at the same time is something that is often limited in tinnitus sufferers and in people whose hearing is impaired”. Neurofeedback could help them to learn to improve their auditory attentional control.

In this process, the activity of the nerve cells in the relevant brain region is measured, converted into an image or a sound in real time, and displayed to the patient as a moving object on a computer screen, for example. They can then try out assorted mental strategies to influence the excitation of the specific brain cells that are involved. If they succeed in this, the effect becomes visible immediately; in such an instance, for example, the object on the screen will change position.

The strategy being pursued in Zurich is primarily concerned with speech processing that is measured using electrodes placed on the scalp of the patient. Daskalou’s project, in contrast, focuses on the activity of the auditory cortex and uses functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). In tinnitus patients, the auditory cortex is often overactive and is suspected of being co-responsible for producing the phantom sound.

More successful therapy

“Those who learn to regulate the auditory cortex using neurofeedback often have better long-term therapeutic success than is the case with conventional behavioural therapy”, says Daskalou, referring to the results of a study in which he was himself involved, conducted jointly by the Wyss Centre, EPFL and HUG.

However, all the scientists involved agree that they need more data before they can start to use such approaches on a clinical basis. Nathan Weisz is the head of the Auditory Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Salzburg. He sums up the challenges they face as follows: “We need robust neuronal measurement data that are reliably related to tinnitus. It’s all the more important, given the enormous effort involved in conducting careful neurofeedback studies”.