BIOLUMINESCENCE

To be a light

The ability to produce light has emerged independently roughly 100 times in the history of life. We take a look at the luminescent organisms that fly thorough the air, live in the soil or dwell in the depths of the sea.

© iStockphoto

Stressful mating

The best-known bioluminescent animals are probably fireflies, also called ‘glow-worms’. But what many don’t know is that these insects glow because their mating season is incredibly short. The common glow-worm, for example, has just four weeks to mate before it dies. Unlike their larvae, the adult insects have no mouthparts and so they can’t feed any more. In order to ensure that males find them in time, the hindquarters of the females glow at night. In another species, the Lamprohiza splendidula fireflies, both the males and the flightless females glow. They have just seven days to mate. In Switzerland, too, they dance in the air in late June and early July.

This bioluminescence is chemically produced, using luciferins. They are a group of molecules that use the enzyme luciferase to react with oxygen, releasing energy in the form of light as they disintegrate. Some fireflies are even able to create a rhythmically pulsating light. Predators such as the Asian orb-weaver spider Araneus ventricosus take advantage of this by capturing male fireflies and using their light signals to attract even more prey.

© ZVG

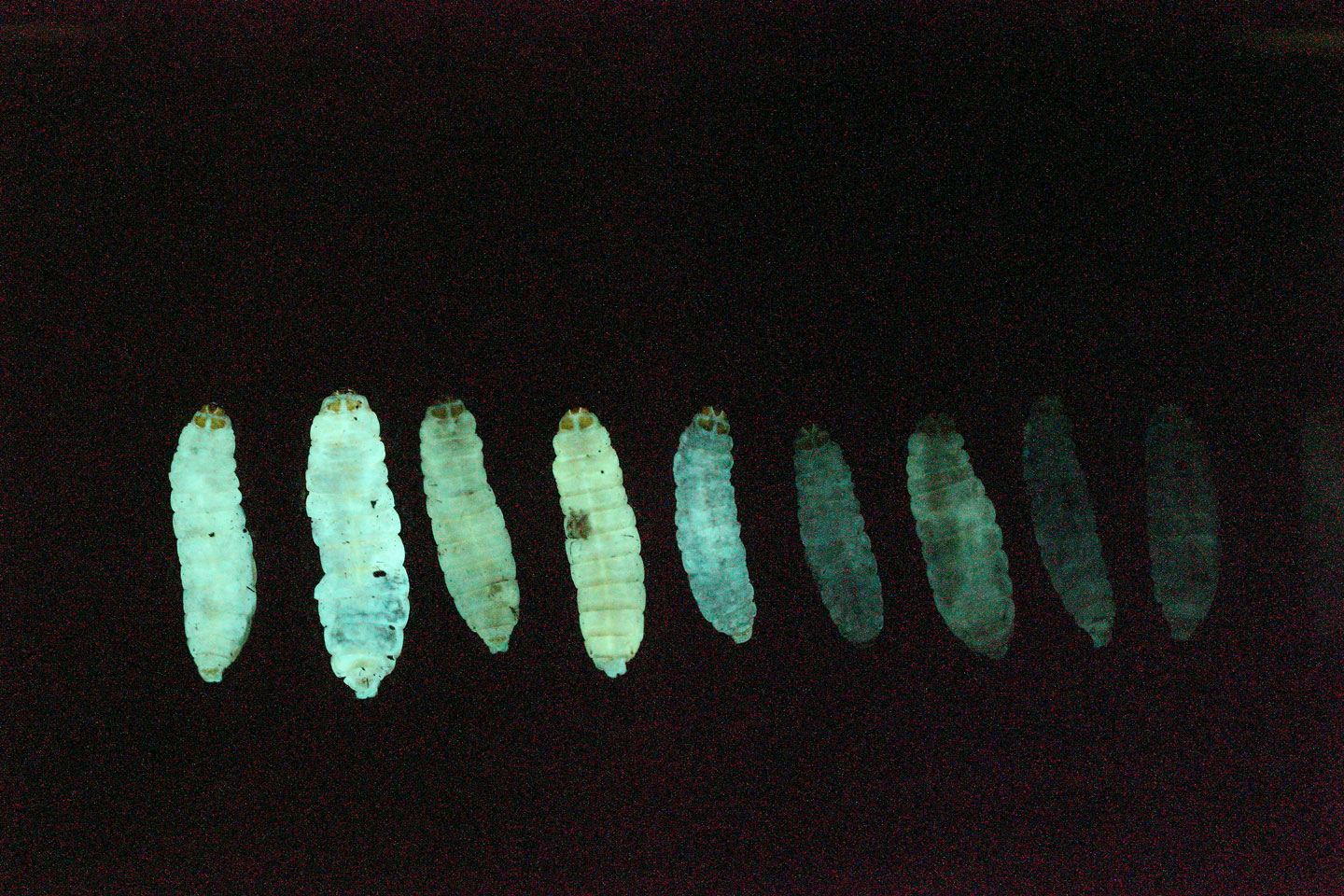

Cunning tricks

Bioluminescence is rare in dense soil. In order to find out what function it might have down there, Ricardo Machado and his team from the University of Neuchâtel have been studying certain roundworms that live in symbiosis with luminous photorhabdus bacteria. They work together to attack beetle larvae, for example. The roundworms penetrate the larvae, which are then killed off by toxins produced for this purpose by the bacteria. The roundworms have a feast and begin to reproduce in the dead insects – at which point the bacteria produce a blue-green light that makes the insect carcasses glow. Machado et al. discovered the reason behind this particular trick by genetically switching off the bioluminescent ability of the bacteria. They were then able to observe how this reduced the bacteria’s ability to form a symbiosis with the roundworms. “This partnership is therefore directly linked to the bacteria’s luminescence”, says Machado. The light also wards off scavenger beetles, precisely during the period when the roundworms are reproducing. So it’s the glow of the bacteria that helps to ensure the survival of the roundworms.

© Nature Picture Library

I glow, therefore I swim

The most animals that glow are to be found in our oceans. At least 75 percent of marine animals that swim have this ability. This fact has been proven by a team of researchers led by Séverine Martini of the Mediterranean Institute of Oceanology in Marseille, using underwater videos that they recorded over a period of 17 years. “Almost everything in the sea glows”, she says. “You just have to look closely”. Marine animals produce light in closed organs, usually in symbiosis with luminescent bacteria. Some small species of squid presumably also use their light to camouflage themselves. These include Abralia veranyi, which Martini has studied in some detail. It possesses tiny light organs distributed over its body that give it a sparkling appearance, allowing it to mimic sunlight in the water and thereby conceal its shadow. This makes it less visible to predators.

Other marine animals communicate using bioluminescence, while yet others use it to attract their prey – such as the deep-sea angler fish. That’s the hypothesis, at least – though Ricardo Machado says: “The function of bioluminescence is difficult to study, not just in the soil, but even more so in deep-sea animals”. Trying to observe them is very complex, and without any kind of non-glowing control group, it’s hardly possible to test hypotheses properly. But one thing is clear all the same: bioluminescence is so strong that there has to be a significant biological reason for it.

© Benjamin Derge

In service of design

Bioluminescence is rare in land-based organisms – and that applies to fungi too. Of the more than 100,000 species of fungus that have so far been described, only 122 are self-luminous. These include the so-called ‘honey mushrooms’ found in Switzerland, which can use their threads or ‘hyphae’ to spread through wood and make it glow. If you’re lucky, you can find specimens in the autumn, especially on wood that’s lying in damp leaves. Foxfire is another phenomenon: it occurs when certain fungi grow on rotting wood, making it emit a mystic green glow. Researchers have found evidence that these fungi use the light they create to attract insects that then carry away their spores – though they still don’t have conclusive proof.

This glow can be put to good use all the same, as has now been shown by Francis Schwarze, a researcher at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Empa). He found a honey mushroom that glowed especially brightly and set about trying to control the light it emits. He has now developed a fungus-wood hybrid that can be made to glow repeatedly over a period of ten months by regulating the moisture in the wood. “We want to create added value for the wood so that it might be used more sustainably in future”, he says. So far, he’s got it to work with balsa wood, which is very light in weight. But he’s also planning to refine native hardwoods to get them to perform in the same way. They could then be used to make furniture or design objects such as ecological night lights – or even jewellery.

© Keystone

Winning a Nobel Prize

The jellyfish Aequorea victoria lives in the Pacific Ocean, mostly off the North American coast. But it has had an impact as far away as Stockholm, where the Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded. In contrast to the vast majority of other luminescent organisms, this creature doesn’t produce light by means of the luciferin/luciferase mechanism, but with a protein called aequorin. When activated by calcium, it emits a blue light that in turn causes the jellyfish’s many small appendages to glow. This aequorin is also able to activate the so-called green fluorescent protein (GFP) that turns blue light into green.

Unlike luminescence, fluorescence requires excitation to produce light. GFP, for example, can be excited by both blue light and ultraviolet (UV) light. Today, we know that if it is bound to a protein being examined in a laboratory, GFP will show you where the protein you’re seeking is located if it’s exposed to UV light. It was for this discovery – and his research into GFP – that the biochemist Osamu Shinomura was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2008. Since then, GFP has become an indispensable tool in molecular biology labs across the world.

© Science Photo Library / Keystone

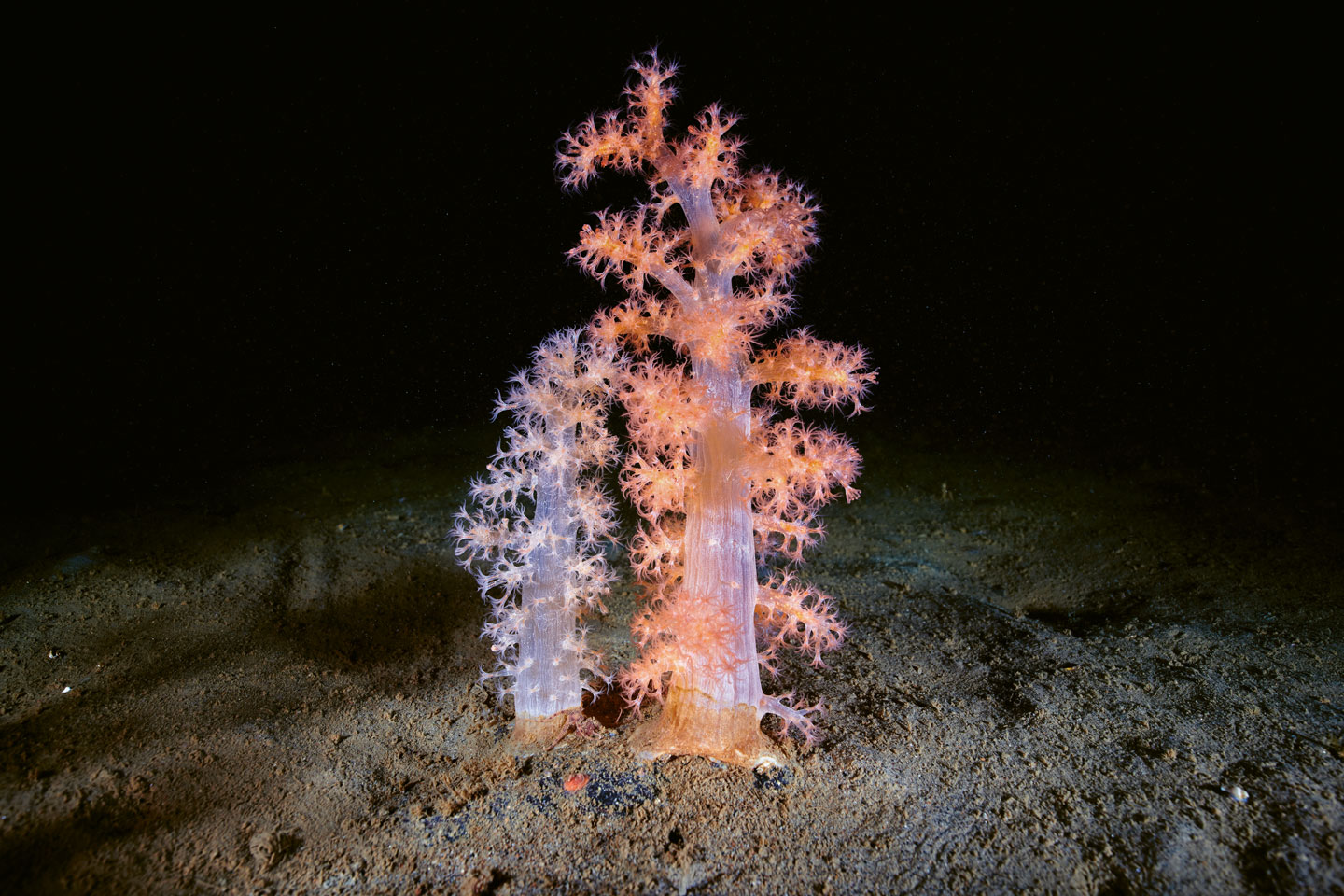

And there was light

It’s been more than 2,300 years since Aristotle already observed how living organisms can produce light. In his treatise ‘On the soul’, he described a ‘cold light’ that came from the sea. Today we know that this marine luminescence is created by bacteria. But bioluminescence itself is much older still. Just how old has become clearer since a study conducted in 2024 in which an international research team investigated the evolutionary history of so-called octocorallia. They analysed a comprehensive genetic dataset and fossil finds of these deep-sea corals (called ‘octocorallia’ because of their eightfold symmetry) and discovered that they developed their ability to glow some 540 million years ago – which was conveniently the same time when animal species first developed eyes. Previously, it was believed that ostracods – a group of tiny crustaceans – had invented bioluminescence 267 million years ago. But in total, organisms from more than 800 genera have developed the ability to glow over 100 times, all independently of each other.