FILMS

When researchers grace the silver screen

The nights are still long. So there’s plenty of time to watch TV series and films! The Horizons editorial team here reviews 12 current productions revolving around laboratories, research findings and the really big questions.

A message sent into space from this isolated Chinese radar station brings catastrophe to humankind. | Photo: Netflix

In 400 years, humanity will be extinguished

“I don’t understand why science is broken”. “I don’t understand it either. But it’s not good. Be glad you’re not a scientist. It’s a shit time for them”. So goes the dialogue between two investigators in the first episode of the TV series ‘3 Body Problem’ from the USA. All the data from particle accelerators around the world contradicts the laws of physics. Several researchers commit suicide. Something’s going really wrong.

A smart but worn-out policeman and five young physics nerds who once worked together at Oxford are trying to find out what’s happening. They’re aided in this by a video game whose immersive qualities are transcendentally good. At some point it becomes clear that the problem is immense. Aliens are going to invade Earth, 400 years from now. They regard the human race as vermin and are going to wipe it out. The researchers have now become jointly responsible for saving humanity. But it’s one of their own number who summoned the alien forces in the first place and thus initiated Earth’s impending doom. Here, science has an ambivalent role to play in the fate of the planet, just as in reality.

‘3 Body Problem’ was developed by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss – the showrunners of ‘Game of Thrones’. It’s based on the first part of the trilogy ‘Remembrance of Earth’s Past’ by the Chinese author Liu Cixin. As in their previous series, they here reveal their knack for telling complex stories. They have largely relocated the novel’s setting to England, but still pay tribute to the epic story’s origins – such as by making some of the most important characters Chinese. But the main characters in the TV series don’t do justice to the original book. They are perhaps less tangible in the latter, but they are nevertheless far removed from any clichés. For the TV series, many of them were rewritten as young, very beautiful individuals, and have been cast with maximum diversity. It’s a bit too much of a good thing.

Researchers were subjected to lethal doses of radioactivity during an experiment that went wrong – but this is what brings about advances in treatment. | Photo: Provided by subject.

Chain reactions from bomb to graft

Falling between drama, thriller and historical film, this feature-length production by the Serbian Dragan Bjelogrlić tells a true and largely unknown episode from the Cold War. In 1958, four Yugoslavian scientists arrive in Paris for treatment. They’ve come straight from the Vinča nuclear research institute near Belgrade, where they were subjected to lethal doses of radioactivity during an experiment that went wrong.

This leads us to discover a crucial stage in the development of bone marrow transplants, which today allow certain forms of leukaemia to be treated. It is steeped in ethical questions, with experimentation on humans using a method that is potentially deadly both for healthy donors and for recipients. And that’s without forgetting its links to top secret research into the atomic bomb.

The film combines a political intrigue sewn with a silver thread to a medical thriller and pleasing ambiguity. It hence swings through the strange microcosm that develops between the patients and those trying to help them, going from human tenderness and scientific coldness. And the scriptwriters have indulged in highlighting the parallels of the protagonist Dr Georges Mathé and the irradiated nuclear physicist Dragoslav Popović, who share a perseverance for their research bordering on obsession and challenging their moral values.

The film alternates between good and less good, making it a feature that leaves a subtle taste of unfinished business. But it has the non-negligible quality of shedding light on an historical event that deserves attention.

This Danish documentary about an evolutionary geneticist relies on visually powerful storytelling. | Photo: Provided by subject.

Danish DNA hunt

For five years, the film director Simon Lec and his crew accompanied the Danish evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev on his mission to decode the DNA of 5,000 people from Antiquity. The result is the documentary film Human Race. It’s currently being shown for the first time, which is why the Horizons team has only had access to its trailer and to a few exclusive clips in the original Danish. “It took these five years”, says the protagonist in the film, “because I show myself to be utterly vulnerable”. It is easy to show success, he says, but difficult to show the defeats that occur along the way.

Past productions of the Danish company Move Copenhagen have already relied on visually powerful storytelling in order to bring scientific topics to a broader audience. The trailer and the film clips we’ve seen suggest that ‘Human Race’ will also succeed in this. The reasons for its probable success lie not least in its main character. Willerslev spent a year living with fur hunters in Siberia, and on one occasion he couldn’t find his way back to their camp before nightfall and almost fell victim to the cold and the wolves. Such real-life stories almost beg to be filmed.

The tornados become increasingly powerful on account of climate change, though this is never addressed directly. | Photo: Provided by subject.

Two lonely geniuses in a storm

The story itself is swiftly told. Kate is a gung-ho PhD student who wants to tame tornadoes using an innovative method she’s developed. It all goes wrong, but her friend Javi encourages her to try again. Then she meets Tyler, the apparent villain of the tale. But appearances are deceptive. They become lovers. All the same, he’s hiding something. At the close, a huge storm threatens a small town in Oklahoma and people and all kinds of stuff fly through the air. Twisters has everything you could want from a good American blockbuster action movie: Lots of beautiful people, plenty of deaths, and a fearless heroine who finds romance.

But science too has its good and bad side here. The storms become increasingly frequent and powerful; this makes climate change the real subject of the film, though without it ever being addressed directly. Given the current political divide in the USA, this is cleverly achieved by Lee Isaac Chung, the film’s director. Everyone will get something out of this movie and do their bit to bolster the box office takings.

Nevertheless, the image of science that the film conveys is pretty dubious. Kate, the meteorologist, and Tyler, a cowboy star on YouTube, are both geniuses who are also lone wolves. They do their experiments in a barn on a farm and develop the most wonderfully ingenious ideas and the coolest stuff – but all on their own, without any supporting team. Kate is also incredibly quick on the uptake. She has a near-sixth sense about where to find a tornado – all she needs is to glance at a screen in the US meteorological institute, or to cast her eyes to the sky when she’s out and about on her tornado hunt in a pick-up truck. Poor Javi, on the other hand, works in a big, impersonal team at the evil company that’s swindling the tornado victims. He has shiny, silvery, high-tech equipment – but it’s not a match for Kate’s brains, just as he can’t enthuse the audience either to the same degree. But this suits the spirit of our times, when so many people are making up their own truths depending on what influencers claim on YouTube or Tiktok. And in any case, it’s great entertainment.

This Swiss thriller about the world of physics offers cinematography like in films of yore, but with patchy execution. | Photo: Provided by subject.

Fuzzy physics in snowy mountains

Johannes Leinert is a doctoral student in physics who’s struggling with his thesis. His supervisor regards him as a failure, though another professor predicts that he’ll one day be a Nobel Laureate. ‘Die Theorie von Allem’ (literally ‘The Theory of Everything’, but marketed in the English-speaking world as ‘The Universal Theory’) is a German/Austrian/Swiss co-production. It offers an amusing depiction of the envious nepotism of the professors and Leinert’s forlornness.

Regrettably, this film is otherwise very much like its protagonist: constantly confused. Its director Timm Kröger has done his utmost, using black-and-white cinematography like the grand old films of yore, adding enigmatic theories about multiverses, magnificent Swiss Alpine panoramas and even a big love affair. But all of this only serves as a backdrop for … for, well, there’s the rub, as it’s never really clear.

A journey back to prehistoric mothers, with a behavioural scientist as our tour guide. | Photo: Radio Bremen and A.Krug-Metzinger Film Productions.

What we can learn from our ancestors

“Could the secret to understanding the cognitive evolution of humankind lie in collective child-rearing?” This question is at the core of the documentary ‘The Secret of Prehistoric Mothers’ by the German journalist and film-maker Anja Krug-Metzinger. She takes her audience on a journey that leads her to village communities on a remote Greek island and to a historically isolated region in northern Germany. In leading us from the Palaeolithic Age to the 20th century, she investigates human behaviour in relation to the cooperative rearing of their young by common marmosets. Viewers learn why the human species – unlike other mammals – is unable to bear children into old age, and what prehistoric graves can reveal about the child-rearing behaviour of our female ancestors.

The ‘tour guides’ on this journey are international names from the fields of behavioural research, evolutionary biology, anthropological forensics and education. It becomes clear once again that it was a combination of cooperation and cognition that enabled humans to rise to the top over the course of our evolution – culminating in events such as landing on the Moon. “But the big question remains: will these achievements suffice for us to master the unprecedented challenges that we shall face in the near future?” This is the question that closes this filmic expedition into the history of humankind. It offers us an impressive, well-founded picture of social evolution in which science places the role of mothers at the heart of everything – without any finger-wagging.

After being abandoned by her professor, a young math researcher wants to throw in the towel. | Photo: Provided by subject.

The intimate face of mathematics

Marguerite is a brilliant mathematics PhD student who presents her thesis work at the École normale supérieure in Paris. A sudden question raises doubts about her results and, after being abandoned by her professor, she herself throws in the towel.

By yanking the mathematician out of the academic world, the plot of this Franco-Swiss film by Anna Novion plunges us paradoxically into its heart. The story tackles a vast range of situations with a subject that’s surprisingly specific: Goldbach’s conjecture, a theory related to prime numbers.

The archetype of the socially mismatched, intense, but self-doubting researcher Marguerite, probably doesn’t perfectly fit anyone. But this role, which earned Ella Rumpf the 2024 César Award (the French equivalent of the Oscars) for Best Female Revelation, has something that resonates simultaneously with PhD students from all fields, with mathematics enthusiasts and with anyone whose boundaries between research and passion tend to blur. More broadly, the narrative questions how to overcome rejection and failure, jealousy, relationships and ambition.

This touching and well thought-out theorem demonstrates with flair what the world of research has that’s visceral, specific, and universal.

The spoof presenter Philomena Cunk maintains a blank expression when asking experts her ineffably idiotic questions. | Photo: Netflix

Dumb questions abound

Science wants to look people straight in the eye, though it rarely succeeds. But why look them in the eye when it can go much deeper? The comedian Diane Morgan, aka Philomena Cunk, offers a masterclass in dumbing down in the British series ‘Cunk on Earth’. She assumes a blank expression when asking archaeologists, philosophers and cultural scientists questions about the world’s big historical events. Her range veers from the ineffably idiotic to the extraordinarily absurd. For example: Does Sputnik mean ‘sperm’ in Russian? Is the music of Beyoncé more significant than the invention of the printing press? And did René Descartes ask himself: “If I thought really hard that I was Eddie Murphy, could I eventually become him? And if I did become him, would he become me, or would he just disappear?”

The interviewee researchers cope surprisingly well in this mockumentary. Some of them really manage to give as good as they get. Douglas Hedley, for example, a philosopher of religion, somehow manages to twist Cunk’s questions so that they suddenly come across as pretty clever. This is great cinema. The military historian Ashley Jackson doesn’t even lose his cool after Cunk accuses him of ‘mansplaining’ for trying to convince her that the sometime communist superpower wasn’t the Soviet Onion [sic]. The cultural scientist Ruth Adams bravely keeps her composure when asked to explain why Elvis’s penis shouldn’t have been shown in the media – though she ultimately breaks down laughing. Cunk, however, remains deadly serious and rebukes her accordingly. Charlie Brooker – the author, director and producer of the series – delights in exposing one of the major weaknesses of science: it takes itself too seriously. But the researchers who participate also manage to demonstrate self-irony. And that’s refreshing.

With drawings overlaid onto real-life footage, Sky Dome 2123 refines its own genre. | Photo: Provided by subject.

In search of the lost scientist

A barren Earth, animal life extinguished, and yet a city survives under a protective dome. Budapest has been saved by a scientist who discovered how to convert humans into energy sources and food: at 50 years old, each person will be transformed into a tree. The scene is set: between a sealed-off life and a chronicled death, lies the perfect dystopia.

Blockbusters in this genre tend to offer an unexpected salvation or a new chance for humanity, in large part through grand special effects. But Tibor Bánóczki and Sarolta Szabó’s animated film blows up in the face of the science fiction universe, and not just due to its Hungarian soundtrack. So, despite the omnipresence of technology in the script, it actually seems superbly ignored: the quest for the scientist who invented the seed that created the Dome is certainly the driving force behind the plot, but the story focuses more on emotions, choices, and personal stories. There are also multiple zones of ambiguity, including characters’ past wounds – that are shown and not told – that give the impression of a complex universe that transcends the film’s boundaries.

With drawings overlaid onto real-life footage, Sky Dome 2123 refines its own genre with both its realistic and ethereal qualities and its resolute singularity. It’s an unexpectedly destabilising deep dive, in spite of the central question hardly being original: must science save humanity at all costs? At the end, the audience is left to judge the protagonists alone: a way to confront the ethical and emotional dilemmas that science sometimes drags along behind it.

In the Planet Earth series, we learn a lot about biology without really realising it. | Photo: BBC One.

The beauties of Nature and their foul pollutants

The BBC Studios Natural History Unit reliably delivers the world’s most impressive wildlife films. Just like those that came before it, Planet Earth III is stunning. It naturally features the voice of British national treasure David Attenborough, who never fails to inspire. We watch close-ups of archerfish that shoot insects off mangrove roots with their spit, only to see their prey stolen by freeloading animals; and we sit and coo admiringly over the babies of maned wolves in the humid Brazilian savannah. And all the while, we’re learning a lot about biology without really realising it.

In this third edition of Planet Earth, the impact of humans on Nature serves as a warning – such as when sea lions get caught in fishing nets and die a miserable death, wailing all the while. The usual ‘making-of’ section at the end of each episode is dedicated to rescue operations. This is an honest, solution-orientated decision. But this new sense of moral seriousness in the series ultimately ruins the magic of the images.

The drama ‘Joy’ tells the story of the scientists who created the first test-tube baby. | Photo: Netflix

An ode to reproductive medicine

Louise Joy Brown was born in England on 25 July 1978. As the first-ever ‘test-tube baby’ she was a sensation. She revolutionised reproductive medicine. Since then, over 12 million children across the world have been conceived using methods such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Brown’s birth was the result of a team effort by the physiologist Robert Edwards, the gynaecologist Patrick Steptoe and the nurse Jean Purdy. It is Purdy who is at the heart of the film biography ‘Joy’ by Ben Taylor. It traces the long journey of many years from the very first experiments to the birth of Brown. The telling is not without clichés – such as making the researchers at Edwards’s lab appear somewhat absent-minded and gauche. Purdy, on the other hand, is here portrayed as a woman whose own endometriosis has been her motivation to help other women to have children. But this also brings her into conflict with her devout mother and the Church.

Overall, ‘Joy’ is an entertaining, instructive science-history drama, though it occasionally lacks depth. The obstetricians here face criticism not only from the Church and from society, but also from established colleagues in the medical field. But such criticism just seems to bounce off the male researchers. This film’s strength lies in its focus on the women involved – not just Purdy, but also those women who agreed to be test subjects, whose own hopes in the new technology were disappointed, but whose participation helped to make possible the birth of Brown. Ultimately, ‘Joy’ is a tribute: Without Purdy, “none of this would have been possible”, says Edwards at the close of the film. He was honoured with the Nobel Prize in 2010. But public recognition for Purdy was a long time coming: it was not until 2015, 40 years after her death, that a plaque featuring her name was unveiled at the site of her former workplace in Oldham.

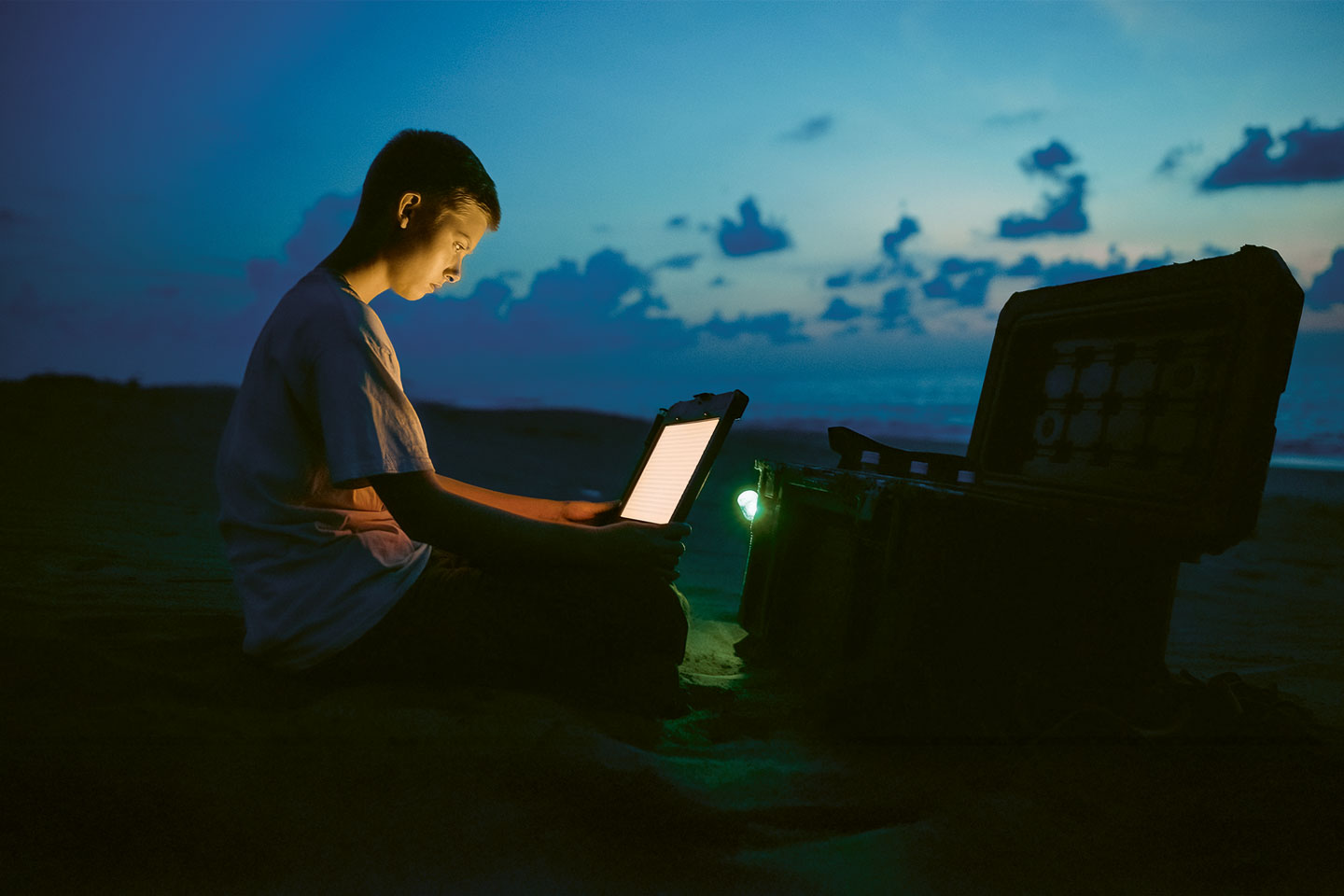

A despairing scientist uses his research to try and save his sick child. | Photo: Netflix

Problems with baby

First, we have to declare an interest. In a sense, this film is also a baby of Horizons. For our issue No. 137 in June 2023, we sent a photographer to the set of this movie by the Swiss director Simon Jaquemet to take pictures for our feature topic at the time (‘Cinema, fact and fiction’). The bleak aesthetic of those images is also reflected in the final film itself.

But let’s get back to the story. The newborn child of Sonny and his partner Akiko has an incurable genetic defect. According to their doctor, the baby has just a 30-percent chance at best of surviving its first year.

Sonny is a successful AI researcher and he refuses to accept this. Instead of enjoying the little time he has with his own child, he concentrates on the abilities of his other baby, an AI he has created. He trains it as a character in a virtual world, where it is itself a child. By giving it access to the Internet, Sonny wants its superhuman intelligence to cure his real child’s illness. Everything naturally goes wrong, and the ending has a few dramatic surprises in store.

The narrative has many different layers and leaves some room for interpretation. It’s about the megalomania of science, about taking responsibility for an AI with a consciousness, and about dealing with one’s personal fate. The research world in which the film is set – with Zurich as the backdrop – seems quite natural, as does its multilingualism (it features English, Japanese and Swiss German). There are a few scientific inaccuracies to help the plot flow, but that isn’t of any real consequence. What’s missing, however, are emotions. The film isn’t really able to touch us – or perhaps it doesn’t even want to.