Report

Where radical feminists line up next to pastors’ wives

It used to be the case that marrying a pastor also meant marrying his profession. The sociologist Ursula Streckeisen has been investigating how the self-image of the ‘pastor’s wife’ has shifted over time. Her primary source is the Gosteli Archive, which holds more than 40 years’ worth of documents on women’s history.

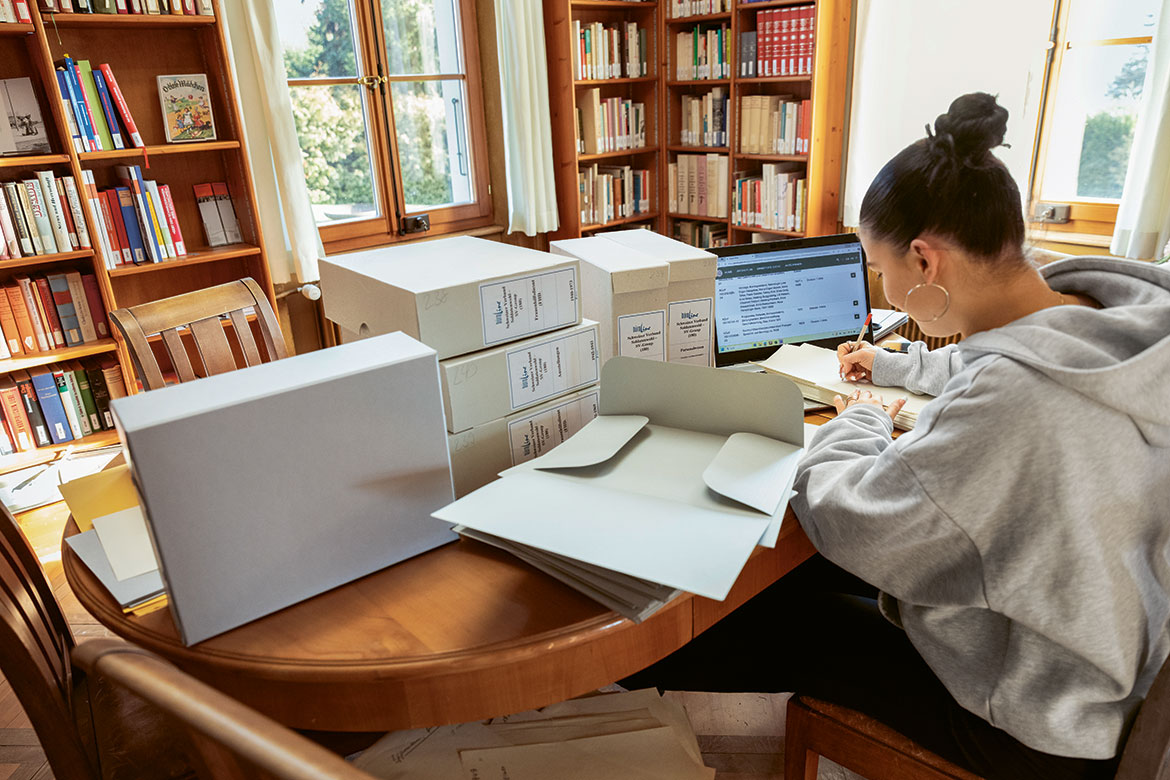

Professor emeritus Ursula Streckeisen is working on two topics in the Gosteli Archive. She’s researching into her own history in the radical feminist movement, and into the history of pastors’ wives. | Photo: Gabi Vogt

The Gosteli Archive in Worblaufen near Bern is housed today in a villa that dates from 1884. When you make your way upstairs, you first have to pass a host of women. The staircase is adorned with large-scale portraits of assorted prominent women including the journalist Agnes Debrit-Vogel, the pedagogue Helen Stucki and the lawyer and politician Marie Boehlen, all pioneers in the fight for women’s political rights, and all arranged here chronologically according to their date of birth. The Archive is named after another woman – Marthe Gosteli – but her portrait doesn’t feature in the staircase series. Hers is displayed prominently in the so-called Gosteli Room on the first floor, which serves as both a library and a reading room.

Gosteli was born in 1917 and grew up on her parents’ farm, just a stone’s throw from here. The Archive is housed on the first upper floor, where her great-aunt once lived. When Gosteli’s father died in the late 1950s, she, her sister and mother assumed the management of their large farm in a world that was dominated by men. From that time onwards, Gosteli was active on the board of the Women’s Suffrage Association of Bern, and in 1968 she joined the board of the Bund Schweizerischer Frauenorganisationen (Association of Swiss Women’s Organisations, today the ‘Alliance F’) and acted as its representative on various federal commissions.

In 1982, she used her inheritance to set up the Archive on the History of the Swiss Women’s Movement. She had good reason to do so, for while there are laws ensuring that official documents are preserved, that is not the case for private documents, which often do not find their way into archives. The political activities of women are thus barely represented in state-run archives.

‘Manning’ the phone

One of the villa’s panelled rooms houses Ursula Streckeisen’s private archives. There are minutes of meetings, pamphlets and suchlike, neatly filed away in ten grey cardboard boxes, that tell the story of the political activities of radical feminists in Bern, Fribourg and Biel. “They were part of the new women’s movement of the late 1970s and early 1980s and they initiated important discussions”, says Streckeisen, a professor emeritus in sociology of the Bern University of Teacher Education and a lecturer at the University of Bern. “I was an active member, kept the written materials, and later gave them to the Archive”. She has a further, close connection to the Gosteli Archive: She is currently spending some ten hours a week researching here into documents of the Association of Pastor’s Wives that was founded in 1928.

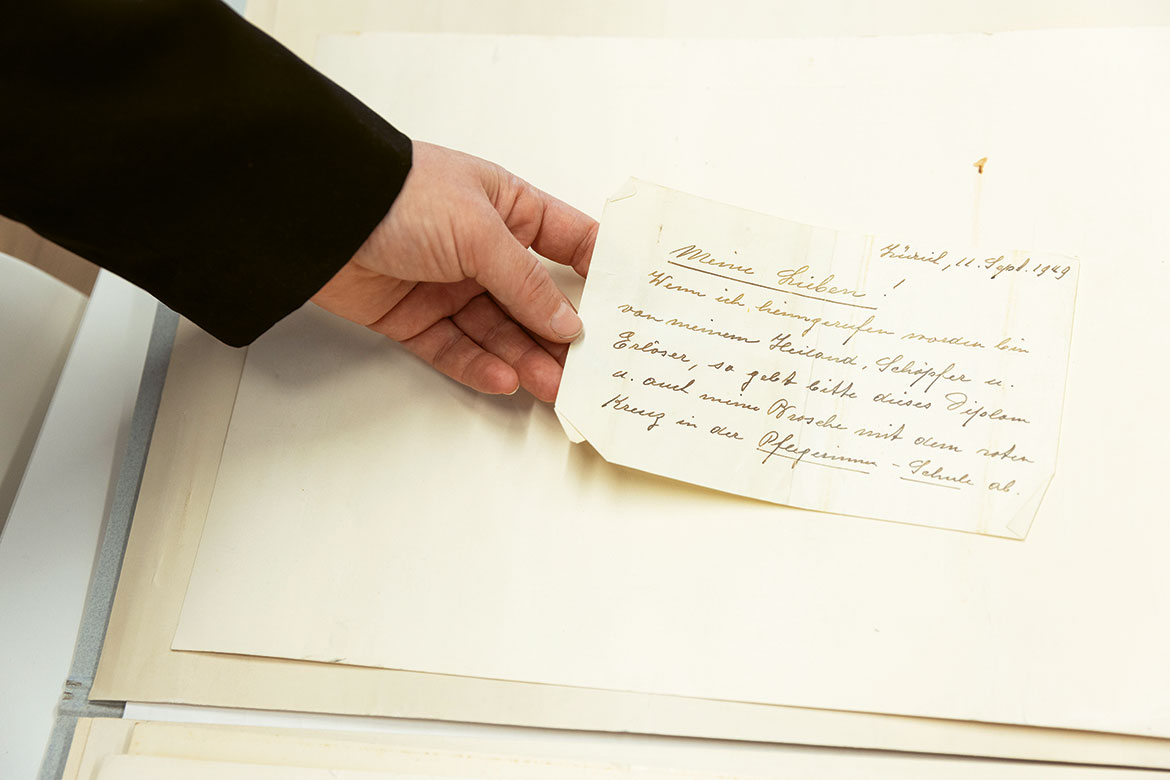

Streckeisen herself grew up in a traditional Protestant parsonage, and she wants to find out how the self-image of pastors’ wives changed over the decades. For a long time, pastors regarded it as only natural that their wives should be at their side as their helpmate: looking after the household and the children, but also taking an active role in the parish itself, essentially being on ‘door-duty’ at the parsonage and ‘manning’ the phone, so to speak, always at hand to see to guests and those seeking help.

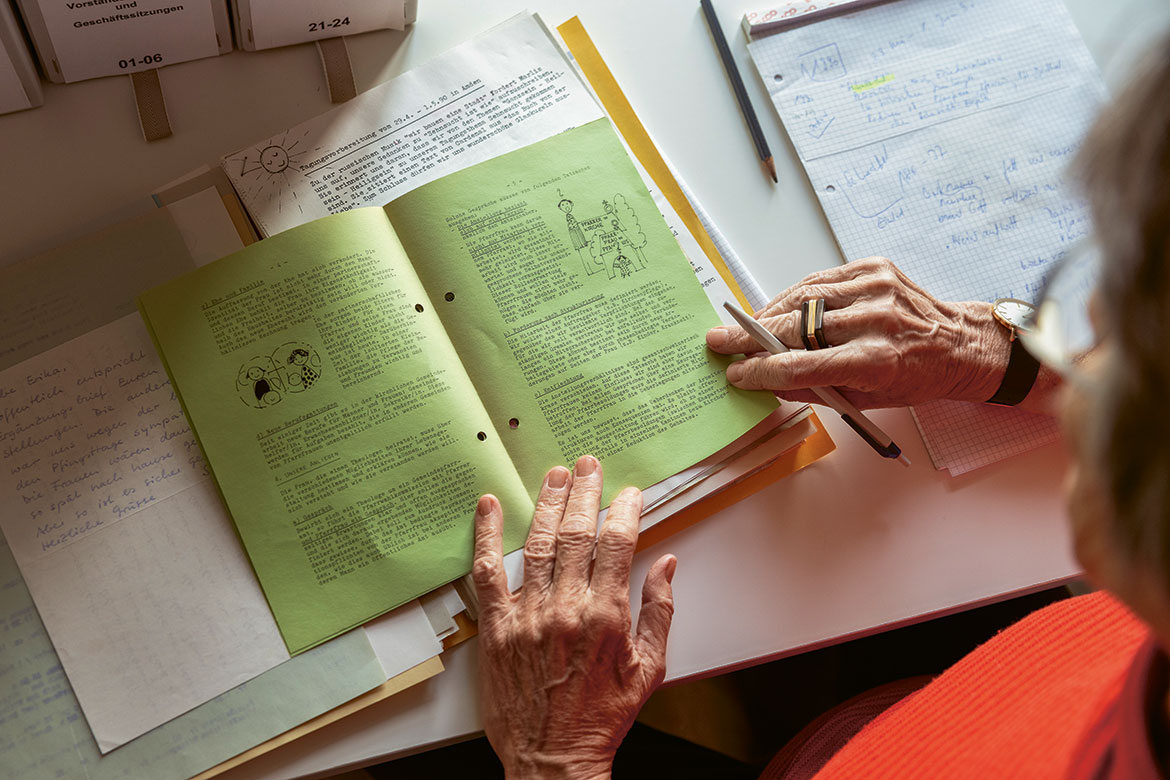

But societal developments over the years inevitably also reached the Protestant Church – including issues such as individualisation, shifts in gender relations and grappling with environmental topics. In 1983, a group of 19 pastors’ wives published a Green Paper with five models for the role of a pastor’s wife. One of the things it proposed was that a pastor’s wife should be free to choose whether to get involved in her husband’s ministry – and if so, how. From today’s perspective this is utterly natural. But at the time, this Green Paper triggered controversy and was also heavily criticised by other pastors’ wives.

“An incredible lacuna”

Streckeisen’s own mother was involved in drafting the Green Paper in question. She was born in 1922, trained as a nursery-school teacher, and after marrying a pastor she initially accepted her traditional role. But later, however, she largely removed herself from the ‘duties’ of a pastor’s wife, returned instead to her former profession, resumed her training and ultimately became a Cantonal Councillor for the Socialist Party (SP). “Such a path was exceptional at the time. Perhaps my own feminist sense of commitment also influenced her a little”, says Streckeisen.

Streckeisen has herself carried out research in the field of professional sociology. ‘Classic’ professions are regarded as academic in nature, typically tailored to men, and are linked to core societal values in fields such as health or the law. Those who practise such a profession become a person of trust for their clients. The traditional pastor is a typical example. In contrast to other professions, however, his profession also involves a parsonage and the parson’s family.

“Work and private life merge in them”, explains Streckeisen. “The classical pastor’s wife doesn’t just marry a man, but also his profession. The pastor in turn marries not just a woman, but also a future assistant”. In this sense, the parsonage is more than just a private residence. It encompasses classrooms, the pastor’s study, and rooms to receive visitors. “And because the parish family is observed as a role model, the parsonage is also seen as a kind of ‘glass house’”, says Streckeisen.

Some ten years after her retirement, Streckeisen began to engage with this topic more intensively because she found it to be “an incredible lacuna” in research terms. The starting point for her work was the aforementioned Green Paper. She originally only wanted to shed light on the pioneering days of the 1970s and 1980s by focusing on two representatives of that generation who had published about their own lives – one of whom was her own mother. She also aimed to work through the associated debates among the pastors’ wives. But in September 2024, the Association of Pastors’ Wives was dissolved, at which Streckeisen decided to include this particular event in her study and to investigate today’s self-image of pastors’ wives. “I’m interested in how these women view their lives and how they fit into the context of society as a whole”, she says.

To this end, Streckeisen is conducting open interviews and using them to construct the women’s biographies. She finds her interviewees through personal contacts, but is also looking for one or more pastors who might be willing to talk about their own experiences. In the Gosteli Archive, she is sifting through the documents of the Association of Pastors’ Wives to investigate more recent discussions, not least those regarding the dissolution of the Association itself and the future of pastors’ wives.

She intends putting her findings into a book or a series of articles. “These pastors’ wives should be made visible”, she says. On the one hand, the fact that she herself is familiar with the scene makes her work easier. “On the other hand, I have to be particularly careful about keeping my distance”, she says. But this is hardly a problem for her: “I have experience in research-related psychoanalytical self-reflection”.

Away with the left/right model

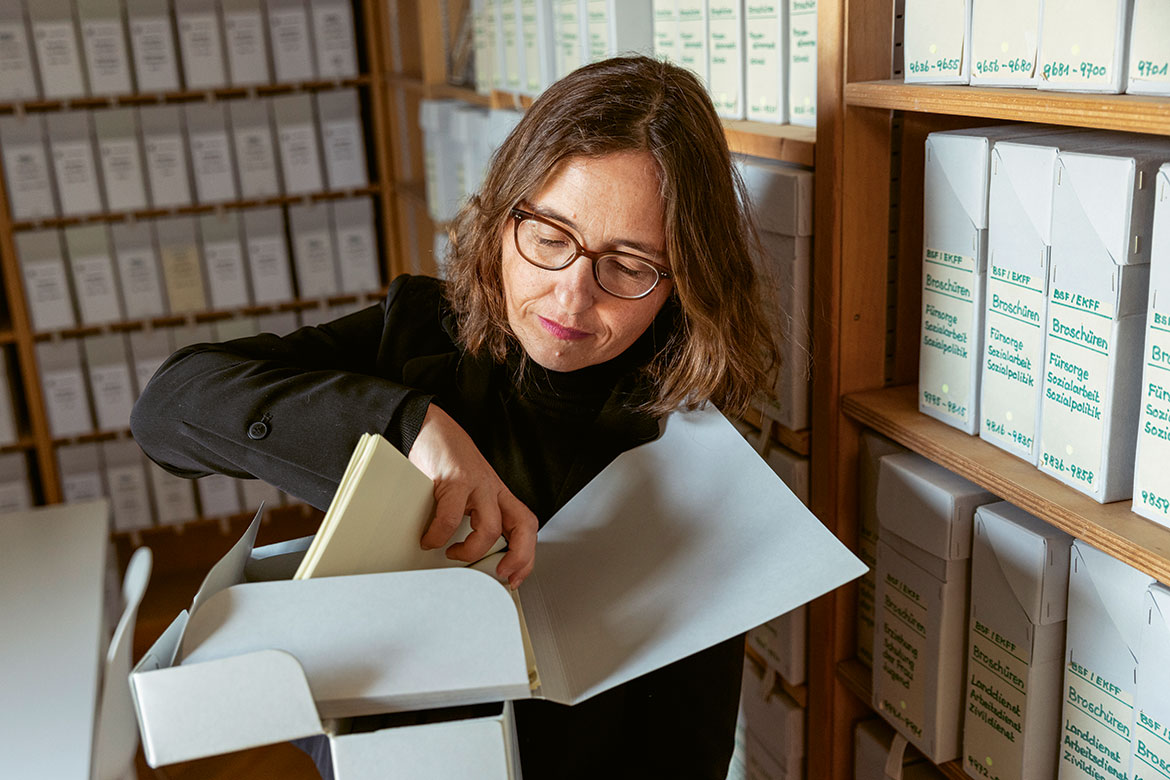

Making women and their history visible: in this, Streckeisen is acting very much in the spirit of Gosteli herself. “If there is no history, there is no future” was one of the guiding principles of the Archive’s founder, as is explained by Simona Isler, the co-director of the Gosteli Archive. The Archive bears eloquent testimony to the diversity of this history, with a total of around one kilometre of files being archived here. Then there are the books and other publications on the shelves.

The largest collection comes from the Association of Swiss Women’s Organisations, while the largest private archive is that of the writer and journalist Katharina von Arx. The archive has been publicly funded for four years, and has eight employees. Until then, the archive had few resources, which is why not all of the documents it has received have been catalogued. “We still have a lot to do”, says Isler.

And there are also systematic gaps. As an example, Isler cites the organisations responsible for migrant women. “French-speaking Switzerland is also underrepresented”. But the Archive has high standards: “We here cover the entire spectrum of the women’s movements – including, for example, female opponents of women’s suffrage”. Among researchers, the Archive is sometimes regarded as covering the so-called old, bourgeois women’s movements, whereas the new women’s movement has found its home in the Swiss Social Archives in Zurich.

“But the women’s movement cannot be pigeonholed into a left/right model”, says Isler. And in fact, Streckeisen and Gosteli provide excellent examples of this: the former is a radical feminist, while the latter was an honorary member of the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (SVP).