Feature: How the cash flows

The race is underway for the best digital currency

The financial world is undergoing a historic upheaval. Digital money based on blockchain technology is becoming increasingly acceptable. But which form is going to win?

Shares, commodities, CO2 certificates – the stock exchange sets the value of many things. The prices displayed used to be an important source of information when trading still took place in the ring. Today in Zurich, they merely help to set the atmosphere at the reception. | Image: Tom Huber

Rumours had been circulating for a long time about Facebook’s supposed plans for a global currency. The big announcement came in June 2019, when the currency in question was officially presented under the name ‘Libra’ – later renamed ‘Diem’. Facebook (today known as ‘Meta’) had some three billion users across the world at the time, and it wanted to establish a new, privately controlled global currency without any connection to the national central banks that create money by printing notes or minting coins. If it had worked, the traditional tools for controlling a country’s economy and ensuring price stability would have become blunt instruments.

“Without the shock caused by Libra, we wouldn’t be as far along as we are today with the digitalisation of money”, says Hans Gersbach. He’s a professor of macroeconomics at ETH Zurich and a co-initiator of the Finsure Tech Hub, where economists, computer scientists, mathematicians and risk analysts teach and conduct interdisciplinary research into technological upheavals in the financial system.

Facebook’s venture woke sleeping dogs, says Gersbach. “The race for the best digital currency has a geopolitical component. It’s also about which one is going to dominate the global economy in the future”. Since then, central banks around the world have been tinkering with their own digital currencies – so-called Central Bank Digital Currencies or CBDCs. Smaller and medium-sized countries such as Nigeria, the Bahamas and Jamaica have already introduced their own CBDCs. The People’s Bank of China has been testing a digital version of its renminbi since April 2021, pilot projects are underway in Canada and India, the European Central Bank (ECB) has been working on the possible introduction of a digital counterpart to the euro since 2020, and the Swiss National Bank (SNB), along with the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the SIX Group, has been pondering the implementation of a digital franc in the financial system.

Cash is losing currency

“What we’re currently experiencing is historic”, says Gersbach. “Technological progress is going to bring about fundamental changes to our monetary system”. The Swiss franc’s status as an international currency could come under pressure if it fails to make the leap into the digital age. “Cash should naturally continue to exist”, he adds. But statistics show that there’s less and less demand for it.

Cash remains the means of payment most frequently used in Switzerland, but the proportion of cash payments has been falling across advanced economies. In Sweden, it recently dropped to practically zero. This process was accelerated by the rise of credit cards, digital transfers and payment apps during the covid pandemic and by the widespread fear that viruses can be transmitted by coins and notes. Cash payments are also being subjected to increasing regulation. In France, for example, an upper limit of EUR 1,000 was introduced in 2016 for all cash payments.

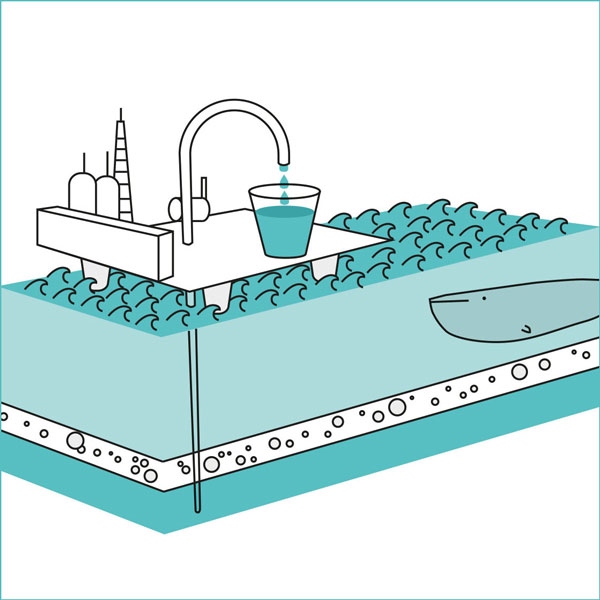

According to Gersbach, if the money of central banks were in digital form, there would be major advantages for the general public. Money would become cheaper because issuing digital francs wouldn’t entail the costs of printing them or the logistics required to distribute them – unlike coins and notes. More importantly, however, “citizens would have direct access to digital money from their National Bank – and thus to a very secure currency”.

Central bank money is the only means of payment that is 100 percent fail-safe – and today, that means money in the form of coins and notes. It’s very different from the digital money used by commercial banks – in other words, the money that’s behind the numbers we see on our computer screens when we use e-banking. That kind of digital money merely stands for a certain amount we are owed in banknotes. If a bank falls into difficulty, that money can simply disappear into thin air. This can lead to the kind of panic we saw most recently in March with the crash of Credit Suisse.

An e-franc can save electricity and reduce risk

Together with Roger Wattenhofer, a professor at the Information Technology and Electrical Engineering Department of ETH Zurich, Gersbach has developed a proposal for how a digital Swiss franc might be conceived. They call it the ‘e-franc’. It should be freely exchangeable for cash and bank deposits and should enable secure payments with today’s standards of anonymity. The e-franc would be issued solely by the SNB, but commercial banks would continue to act as intermediaries between the SNB and private individuals.

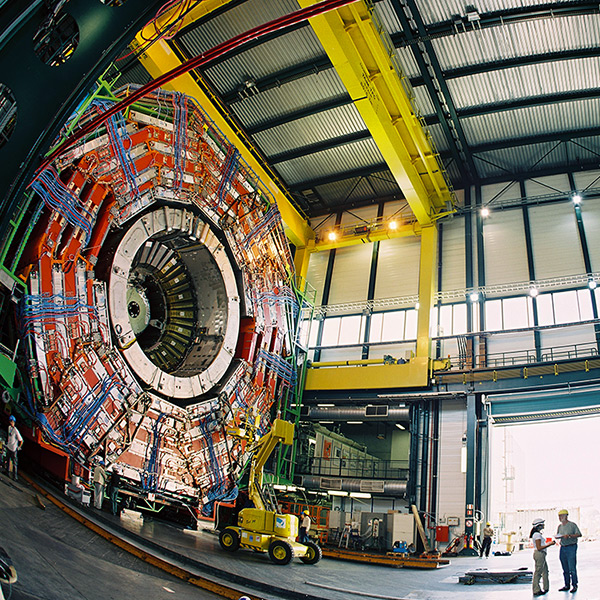

This system would run on a blockchain with two separate levels. One would be responsible for the security and validation of transactions, the other for the connections between payers and recipients. This ought to make the system swift, scalable and secure. Unlike Bitcoin, for example, the e-franc would not require a so-called ‘proof of work’; in other words, a transaction would not need any qualification across thousands of nodes on the Internet, which eats up huge amounts of electricity. Verifying the e-franc would be done through a few predetermined agents. “The energy input would therefore be roughly the same as is the case today with bank transactions over the Internet”, says Gersbach.

The study he has conducted with Wattenhofer shows that the digitalisation of the Swiss franc is feasible from both technical and regulatory standpoints. It’s also desirable for the public, says Gersbach. This is because the e-franc can have a disciplining effect on commercial banks. For every digital franc that customers request from their banks, commercial banks would have to possess an equivalent reserve to buy it from the SNB. They would not be able to create e-francs themselves, as they do today with book money. “Commercial banks would have to place themselves in a position that is more crisis-proof”. The consequences would be a reduction in risky credit transactions, less volatility, and fewer financial bubbles in the economic system.

Bitcoin was only the beginning

For a brief moment in late 2022, it looked as if cryptocurrencies might after all be nothing more than sleight of hand and a big hype. Facebook’s money project had failed. The value of Bitcoin also plummeted, losing around 60 percent of its value between January and November 2022. But this is by no means the end of cryptocurrencies, says Aleksander Berentsen, a professor at the Faculty of Economics at the University of Basel. His research interests centre on blockchain and crypto-assets. “Of course there are plenty of shady fortune hunters among cryptocurrency traders, and in some cases it’s really like the Wild West out there. But it doesn’t change the fact that blockchain technology will prevail in the financial sector”.

In research today, the focus is increasingly on stablecoins. These are cryptocurrencies whose prices are supposed to remain stable, and against which assets are deposited – which is not the case with Bitcoin. This, at least, is what their issuers promise. The blockchain-based Ethereum platform has established itself as a place for creating and trading different stablecoins. “Ethereum is significantly more efficient than the previous financial infrastructure”, says Berentsen. To illustrate this, he gives the example of Uniswap, a decentralised crypto-exchange on the Ethereum blockchain. It was developed in November 2018 as an open-source project by Hayden Adams, a former Siemens engineer. In terms of turnover per employee, it is today already vastly superior to centralised exchanges like Coinbase or Nasdaq. In 2021, Uniswap had 37 employees and took in over $1.2 billion in fees; Nasdaq had over 4,700 employees and took in $3.4 billion.

The so-called ‘smart contracts’ that underlie Uniswap’s system are what make the decisive difference. They allow innumerable functions to be programmed for a digital medium of exchange – such as automated controls against money laundering. The ‘know-your-customer’ regulation of the national banking oversight boards can also be automated using so-called ‘whitelists’. Berentsen anticipates that a whole ecosystem of new services for the financial sector will emerge around the Ethereum blockchain, including new digital currencies in the form of private stablecoins. He believes that everyone in future will have a private crypto-account, and that a large part of the financial system will migrate to a blockchain-based infrastructure. Cash will disappear in the medium term, to be replaced by competing cryptocurrencies that allow for a limited degree of anonymity.

Everything can be seen forever

When Facebook announced its plans back in 2019, many were afraid that having its own cryptocurrency might have enabled it to gather even more data about its users than it already has today using Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. People feared that our overall privacy would be further eroded. This is why legal experts are also arguing that nation states shouldn’t simply leave issuing digitalised currencies to the private sector. The Libra experiment might have failed, but it’s an open secret that other tech corporations, e.g., Google, are also interested in cryptocurrencies. It’s against this background that TA-Swiss, the Foundation for Technology Assessment, recently launched a call for risk assessments of new, virtual forms of money. The call states that private companies could gain “significant financial and political influence” and that globally distributed currency systems of private companies might “challenge existing approaches in the regulation of payment transactions at the national level”.

According to Harald Bärtschi, a legal expert and a titular professor at the University of Zurich: “Introducing a digital franc will also require a political discussion about just how much data protection will be necessary, and how much transparency is justified”. He is specialised in legal issues surrounding financial technology and blockchain. A public blockchain will naturally make deleting data practically impossible. All transactions will be stored permanently and will be able to be viewed on the ledger. After all, traceability and transparency were the big promise that blockchain made when it started, even though Bitcoin is today one of the most popular means of payment for organised crime and hackers.

Cash, in contrast, is notable for the fact that it leaves practically no data traces. How could a crypto-based e-franc ensure our right to be forgotten – such as in the case of personal transactions dating back several years? And what will happen to our right to privacy and data protection if all private money transactions are visible to the operators or authorities on the blockchain?

Swiss politicians are hesitant

It remains uncertain as to whether Switzerland will be one of the pioneers of digital currencies – despite the canton of Zug’s so-called ‘Crypto Valley’ and Switzerland’s considerable investments in research and development. In a report of 2019, the Swiss Federal Council concluded that if the SNB created generally accessible digital money, it would not bring any additional benefits for the country. When asked to comment, the SNB responded by saying that various projects are currently underway for a CBDC, but that they are “purely exploratory in nature” and “should not be understood as an indication for or against the introduction of a CBDC”. Hans Gersbach says: “Politics is dragging its feet, and people have become even more cautious since the Credit Suisse crisis. That’s unfortunate, because an e-franc could eventually help us to solve the too-big-to-fail problem”.

Gersbach believes that the gradual introduction of an e-franc would stabilise the financial system without new, costly regulations having to be introduced. He is also convinced that the e-franc, coupled with the possibilities of smart contracts, would increase competition on the financial markets. After decades of concentration, this could help the financial sector to achieve greater decentralisation once again. So it’s hardly surprising that the big commercial banks and their representatives in parliament are scared of the possible upheavals. Their privileges are threatened, primarily the privilege of creating money themselves, which in turn enables them to conduct highly risky but profitable business that is often quite detached from the real economy.

All the same, Gersbach believes that an e-franc could also be introduced very quickly. “Progress on the e-euro will also put pressure on Swiss politicians”. Provided the EU member states and the ECB Governing Council are on the same page, the e-euro could be available as early as 2026. It is likely that a minimal version of a digital franc will become established in a few years, believes Gerlach, with restrictions on its conversion and a long introduction phase. This would be far less disruptive than Silicon Valley’s tech companies might like. But it would at least be democratically legitimised, it would have a firm legal basis, and it would be economically sound.