Clinical trials and tribulations

Some laboratory studies are being scuppered by overly optimistic researchers

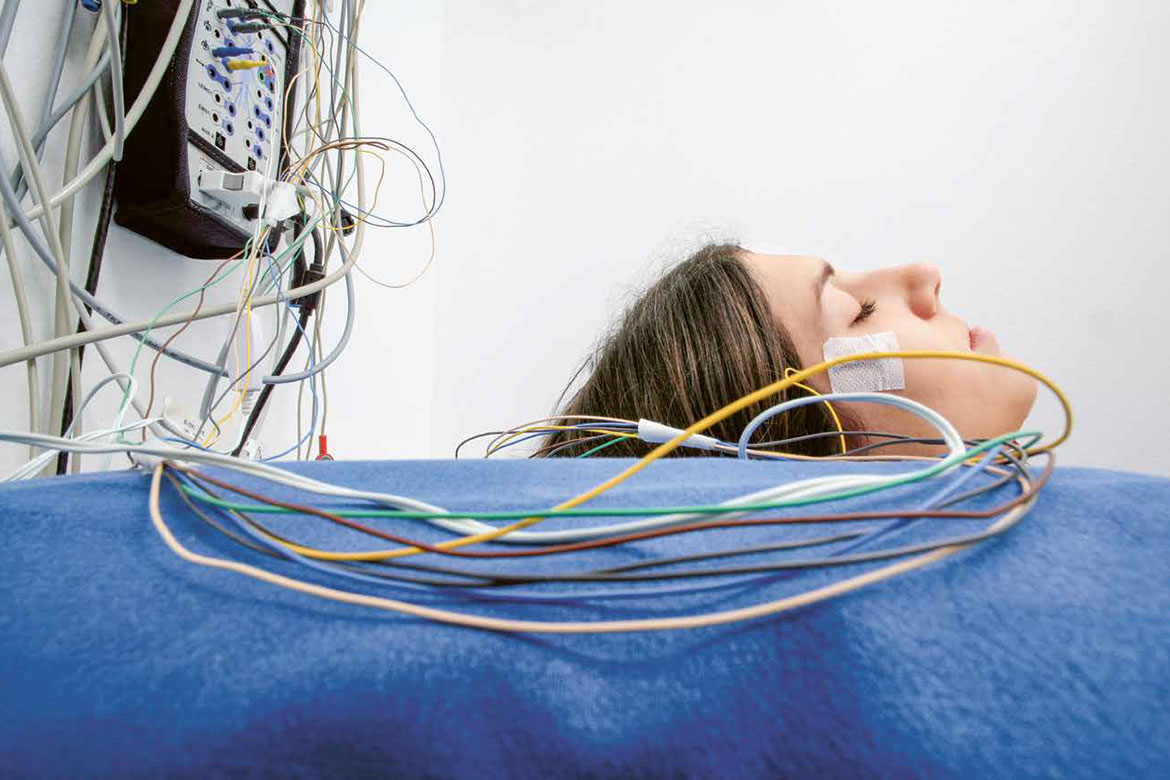

Is Switzerland missing the bus when it comes to international clinical research? Without the proper personnel resources, you can’t carry out a well-organised intervention study. Image: Keystone/Science Photo Library/Look at Sciences/Massimo

Randomised controlled trials (‘RCT studies’) are essential for medical progress. But their cancellation rate is appallingly high. For example, one out of four studies funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation SNSF between 1986 and 2015 was cancelled early by its researchers. This is the conclusion of a team led by the Basel epidemiologist Matthias Briel, whose results have now been published in the British Medical Journal.

It makes no difference whether the projects are funded by the SNSF or not. “It’s a fundamental problem”, says Briel, who is researching at the Basel University Hospital. His team has analysed why so many RCTs end ahead of schedule. The main problem, they find, lies in the early stages, namely in the recruitment of suitable participants. “Often, the researchers’ estimates are too optimistic”, says Briel. In other words, the doctors are confident there will be enough patients taking part without properly ensuring that the numbers are right. In reality, not every patient will fulfil the inclusion criteria of a study, nor will everyone will be willing to participate either. Especially where a lot of effort is involved.

Annette Magnin has experienced similar problems. She’s the Managing Director of the Swiss Clinical Trial Organisation (SCTO): “Researchers often overestimate their participant numbers by some 50 percent before their studies even begin”, she says. The SCTO was founded on the initiative of the SNSF and the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) in order to support doctors in clinical research.

Federalism limits the patient pool

“Another problem is that many studies are too regional in how they’re organised”, says Professor Peter Meier-Abt, the Vice President of the SAMS. Many hospitals in Switzerland are too small to be able to rely on a satisfactory pool of patients. The health system is organised on a federal basis, and most experts see this as a core issue in the optimal organisation of a clinical study. “We really need an overall pool of patients”, says Meier-Abt. But coordinating such a pool across all of Switzerland is difficult. Briel also believes that “you don’t have to limit things regionally to a single Swiss hospital”. Studies that are run in several places can function very well if they are properly prepared and coordinated.

The experts are also of one mind with regard to another object of criticism: that doctors in Switzerland are much too involved in everyday clinical work. “We need more time to be allocated specifically for research”, says Meier-Abt. Doctors who are already putting in overtime can’t carry out research on their free evenings or at weekends. Magnin also says: “Treating people is what actually brings in money for the hospitals; but as time goes by, it gets more and more difficult for their clinical personnel to invest time in research too”.

“We have to be careful that we don’t miss the boat, internationally speaking”, says Meier-Abt. Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands are far more advanced than Switzerland when it comes to research infrastructure. And in the Anglo-Saxon world, scholarly work carries far more weight.

The first initiatives are up and running

Initial attempts are being made to combat this problem. Two years ago, the SNSF initiated the programme ‘Investigator Initiated Clinical Trials’ (IICT), with which it hopes to promote independent clinical research in Switzerland. There is a budget of CHF 10 million available in 2017. “We have extended the duration of RCTs from three to four years”, says Ayşim Yılmaz, the head of the Biology and Medicine Division of the SNSF. This is intended to make it easier for researchers to carry out a proper preparatory phase. “We also want to invest in innovative research”, says Yilmaz. There are no guarantees that a trial will succeed, but failure shouldn’t be used to excuse poor planning”.

Preparing something well is the best path to success, says Matthias Briel, who is himself the author of a clinical study: “It’s best to carry out a controlled pilot study with the same study protocol”, says Briel. Doctors aren’t always enthusiastic when they hear this, but various international investigations have confirmed it as a recipe for success. What is also decisive, says Briel, is describing the recruiting process in detail in the study protocol. “The researcher should also run through the ‘what-if’ scenarios at the preliminary stage”, he says. “That way, you can minimise the damage, should your search for participating patients be proceeding sluggishly”. Briel sees social media platforms as a means of expanding the potential group of participants. Initial trials have shown that social media can help to stimulate interest in a study. Overall, the general public has to be sensitised to the fact that clinical research is for the good of everyone, but that it’s only possible if a lot of people are prepared to participate in studies.

The ethics commissions could also do their part in making the recruitment process as successful as possible. “When assessing studies, they ought to make the researchers already aware of possible shortcomings in recruiting participants”, says Briel. In the past, he adds, doctors have repeatedly complained that the administrative burden caused by such studies is a major hurdle. Meanwhile, the procedure has been somewhat simplified.

Research has to be learned

The experts are also united in their belief that more should be invested in training young researchers: “Planning and carrying out clinical studies correctly is a discipline all of its own – one you have to learn”, says Magnin. Clinical Trial Units exist today at six Swiss hospitals and act as service providers to the researchers. But their support is costly. Last year, the Federal Office of Public Health launched a roadmap for promoting young clinical researchers. One part of this package entails the creation of a Swiss Clinical Research Education Centre. “Here in Switzerland, we need a clear commitment to clinical research”, says Magnin. Briel is also insistent that “all the key stakeholders must participate in these efforts, and assume their responsibilities in this vital field”.

The question remains as to what should happen with the data that is left unused after unfinished studies. “It should be made generally available to later studies, either for meta-analyses or as lessons learned”, says Briel. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in Britain, for example, solved the problem by insisting that all studies it supports be published. If that condition isn’t fulfilled, they don’t get any money.

Alexandra Bröhm is a science journalist at the Tages-Anzeiger and the Sonntagszeitung.