Feature: Much ado from nothing

“OK, so you’d like to die. Tell me more about it”.

What happens if someone feels only emptiness? Or even longs for the nothingness of the end? Emmy van Deurzen is an existential psychotherapist who gazes with her clients into the abyss – but then draws strength from it.

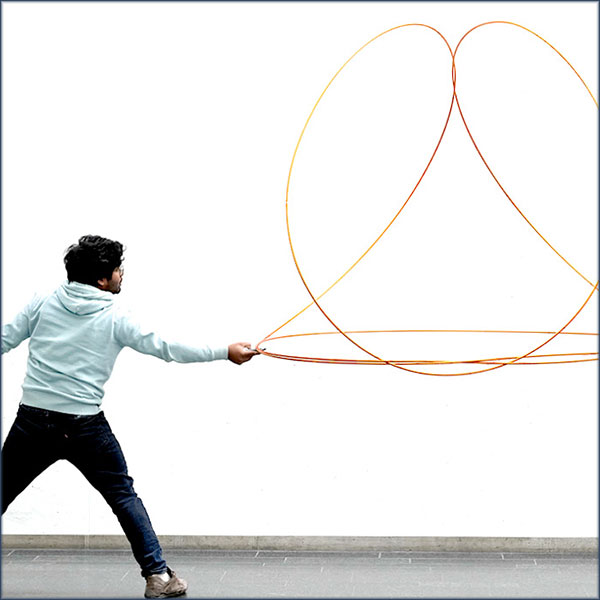

When she was a teenager, Emmy van Deurzen tried to take her own life. Today, she’s a psychologist who uses her own experience as a basis from which to help people in despair. | Photo: Lily Miles

Emmy van Deurzen, you work with people who’ve endured war and catastrophe. How does someone cope when nothing is left of their previous life?

When I was a young therapist, I worked a lot with Holocaust survivors. Later, I worked with people who’d experienced the wars in Vietnam, in the Balkans, in Afghanistan, and currently in Ukraine. What I have realised time and again is that there is no formula to this. Some people emerge incredibly in one piece from loss and horror. They’re able to take on huge challenges and find their purpose in life. Others, however, react with deep distress.

Existential help

Emmy van Deurzen (73) was born in the Netherlands and works today as an existential psychotherapist, philosopher and counselling psychologist. She’s a visiting professor at Middlesex University (UK), where she runs several doctoral and master’s programmes. She is also the founding director of the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling in London. She runs her own therapy practice, and is president of the worldwide Existential Movement.

What’s special about those people?

It’s usually people who find themselves back in a passive role, for example, women whose male partners are away at war and who feel completely abandoned to their fate. But existential crises can have very different causes. Maybe someone has lost their job, or their home was burgled, or they’ve lost hope in the future of the world.

You work with existential psychotherapy, which aims to help people discover their values and to find a meaning to their lives. This also includes looking at the ultimate nothingness: death. Why is this so important?

It’s generally quite fundamental issues that lurk behind the initial concerns that prompt someone to seek therapy. Questions such as: Who am I? What is the point of my life? How can I deal with my mortality? I think that most psychological problems are connected to the fact that we have lost the purpose of our existence. If we address these questions, we soon realise that we ourselves can find the answers. What’s more, we find that we have long been connected to everything that really matters in life: to the people we care about, but also to the ideas and things that are important to us. And we find that we possess the ability to understand life and, step by step, to live more freely.

Gazing into the abyss

Existential psychotherapy is a philosophically based approach to counselling and therapy, as described in the Wiley World Handbook of Existential Therapy, published in 2019. It grapples with fundamental questions such as: Who am I? Why am I here? How can I cope with my finiteness? How should I live my life? This form of therapy does not provide any quick solutions. It’s based on the understanding that through perseverance, courage and a readiness to look into the abysses and dark sides of life, people can succeed in making something of the time that they are given.

You yourself were confronted with death at an early age. As a ten-year-old, you barely survived a serious traffic accident.

I was in hospital for weeks after the accident with serious head injuries, and I wasn’t allowed to move. I remember very well just how worried the people around me were that I might die. But I had neither any concept of death, nor any fear of it. I was more concerned about how life would go on: had I sustained injuries that could make it impossible for me to lead a normal, everyday life? From that moment on, it was obvious to me personally that dying is the easier way. It is difficult to live with everything that life throws at you. This became very clear to me when I had my heart broken as a teenager. I tried to take my own life at the time. Death to me was a safe haven that would offer me refuge.

What impact do these experiences have on your work today?

This image of death as a safe haven has stayed with me to this day. It gives me a firm foundation for when I work with suicidal people. I can have a therapeutic conversation with someone without feeling that I have to stop them from committing suicide. I can sit across from that person and say: “OK, so you’d like to die. Tell me more about it”. I am very close to my client in these moments and can cope with their despair. As a therapist, the courage that lets me look into their abyss is then also transferred to them.

What exactly does that mean?

It means that at some point, those people take a leap to explore ways to let go of the life that has driven them so deeply into suffering – but ways other than suicide. If you’ve dared to look your own death squarely in the eye, then you can take both the despair and the immense courage that’s needed to contemplate suicide, and channel them into changing your life. I want to lead my clients to this realisation. There’s always something that’s dear and precious enough to us that we would want to retrieve it from the flames. We just have to know where to look.

Depression is often described as an inner emptiness – sometimes as an absence of any feelings at all.

Even when all emotion seems to be absent, I’m usually able to discern an emotional response from people within just a few minutes. There’s always something that frustrates us or irritates us – whether it’s the food we’re being served or a sore throat. It’s precisely at that point that we therapists come in.

What does that mean?

We observe their everyday annoyances, worries and desires with a view to very gradually applying this knowledge to discern the entire fabric of their human existence. From the perspective of existential therapy, depression is triggered by someone having made their life very, very small. They are no longer giving themself space for thoughts of the past or dreams about the future. They’re no longer allowing themself to be in the here and now with all their senses. But it’s precisely these processes that let us expand and enable us to take our place in the world.

When I’m in the bus, I often have the impression that hardly anyone bothers just to look out of the window anymore to let their thoughts wander. Everyone’s on their smartphone. Are we losing the ability to do nothing?

We all live these overcrowded lives. Our days are full of distractions and everyday problems that at some point get to seem insurmountable. We start to think that we’re constantly dealing with our lives – though these thoughts mostly just distract us from the actual question, namely: what are we really doing here? Because that is the paradox: It’s only when we allow emptiness to exist, when we allow ourselves to be open, not to know, not to do things, that we are fully present in the moment. This means welcoming whatever happens in life, and not hiding away from our feelings, whatever these may be. If we can do this, then we will once again know who we are, and we shall become aware that everything is already there, in each and every one of us.

According to a widely discussed study by the University of Virginia in 2014, an astonishing number of people prefer being given an electric shock to being alone. This interpretation of the study has meanwhile been subject to criticism, but there is still one thing that everyone seems to find problematic: An idle mind will always turn to the next problem instead of dwelling on pleasant thoughts. But is that really such a bad thing?

After more than 50 years as a therapist, there’s one prognosis that I can make with absolute certainty: as sure as death will come for us one day, life will present us with new hurdles absolutely every day. But we are designed to tackle problems, to be creative and imaginative. We should take this fact seriously, and not try to avoid it. Perhaps the meaning of life lies precisely in the fact that we shouldn’t worry about difficulties and setbacks, but rather accept them and get to grips with them – even relish them, because they show us that we’re alive.