INFLAMMATION

Gums on a microchip

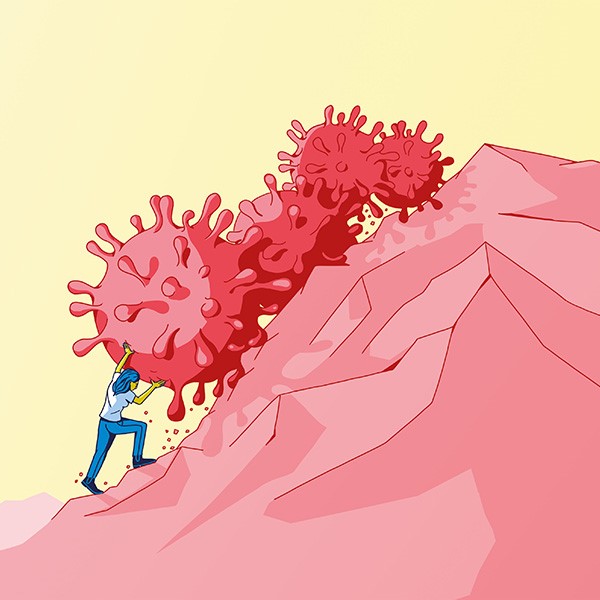

An innovative model for periodontitis can help provide answers about the progression and consequences of this painful inflammation.

Between 20 and 40 percent of the population suffer from inflammation of the gums. | Photo: Jim Stevenson / Keystone

For some years now, it’s been possible to grow mini-organs in a laboratory that contain the same essential structures as their real-life models. In other words, mini-intestines contain the same structures as the digestive tract, and a mini-placenta similarly contains the structures of a real one. Some research teams are now transferring such mini-structures onto microchips. Petra Dittrich, a chemist and bioanalyst at ETH Zurich, has reported how her research team has for the first time been able to create a cube of tissue on such a chip, along with blood vessels and cells from the periodontal ligament tissue. They have even been able to allow fluids and nutrients to flow through their cultivated tissue.

“This model is intended to help us achieve a greater understanding of the development, progression and treatment of periodontitis”, says Dittrich. Some 20 to 40 percent of the population today suffer from this inflammation of the gums – and experts in dental medicine know all too well that periodontitis plays a role in strokes and heart attacks. It’s even thought that it might be co-responsible for the early development of Alzheimer’s. “We already know a lot about how periodontitis develops, but we don’t know much about how it affects other organs”, says Dittrich.

For this project, Dittrich’s team worked with the oral biologist Thimios Mitsiadis from the University of Zurich to take cells from the periodontal tissue of a healthy human tooth and bring them together with cells that are important for the development of blood vessels. These two cell types were placed in a hydrogel where they together grew into a cube of periodontal tissue a few millimetres high. “We can use this tissue to simulate the inflammatory processes that take place in the human body”, says Dittrich. This would be impossible in flat, two-dimensional cell cultures. But using her microchip, Dittrich can now observe under controlled conditions how the inflammation progresses and how the tissue changes as it does so. Her first experiments have already been highly promising.