Feature: Much ado from nothing

Not so empty

Physics teaches us that empty space is not really empty. It contains matter, energy, and even the keys to the fate of the universe. To the point where it challenges the notion of ‘nothing’. We take a philosophical journey to the boundaries of physics, and vice versa.

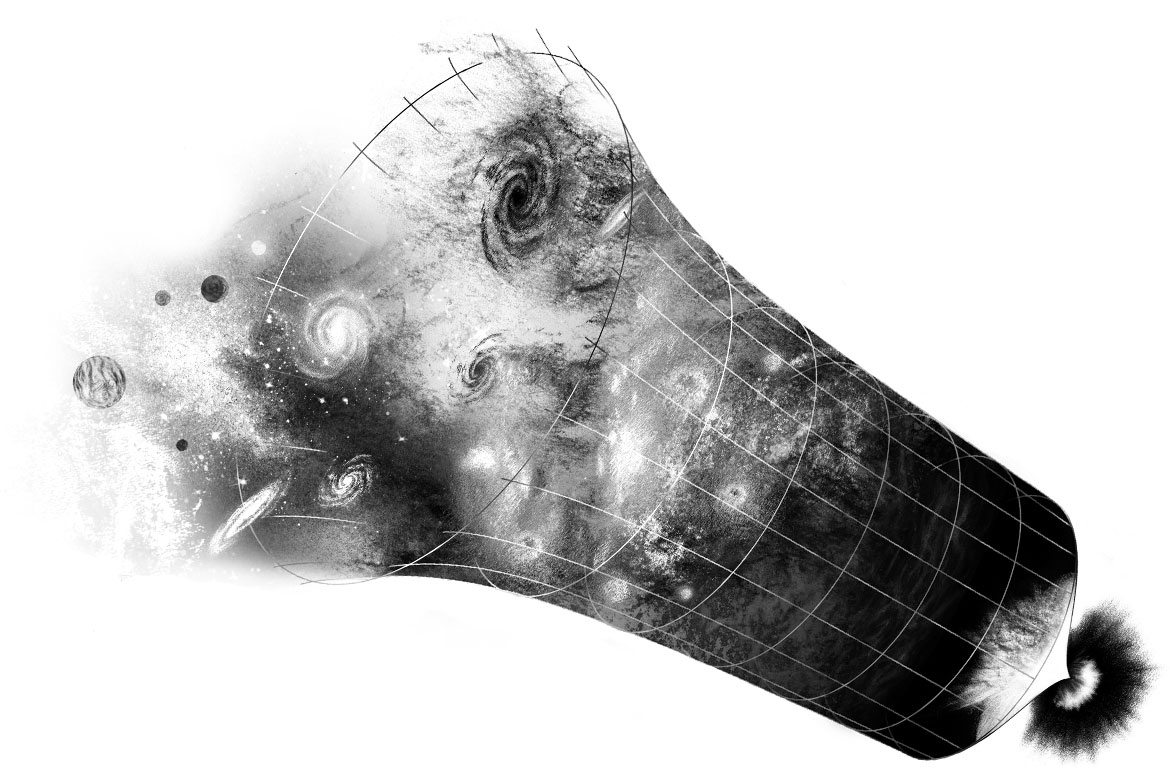

A view of the universe in times long past, when it was still small and dense. | Illustration: Michael Raaflaub

‘Does empty space exist?’ The approach to this question requires considering both the infinitely large and the infinitely small. On the way, we can recall ‘the worst theoretical prediction in the history of physics’ and at the same time discover the various fates that physics predicts for our universe. By defining it as the absence of everything else, understanding the void pushes us to understand the whole. “A void can be seen as a gradation of absences, each physical theory having its own conception”, says Baptiste Le Bihan, a professor of philosophy at the University of Geneva. For Norma Sanchez, an emeritus physicist of Paris Sciences et Lettres University, “the concept of void is not absolute; it evolves”.

For ordinary mortals, empty space, or a vacuum, corresponds to the absence of air. It’s never perfect, as it still contains a large number of air molecules, but it has many useful applications, from preserving food to producing electronic circuits (see box). A lesser-known property of a vacuum is the force it contains: in 1656, the German scientist Otto von Guericke showed that two teams of eight horses could not separate two metal half-spheres with a diameter of 42 centimetres that were held together by a lack of air. This resistance results from atmospheric pressure, which only acts on the outside of the spheres and not inside. Vacuum therefore derives its force from the non-vacuum that surrounds it.

The best vacuum on Earth can be found in research laboratories, particularly in the tunnels of CERN near Geneva. The pressure there is a thousand billion (1012) times lower than that of ambient air. But this is nothing compared to outer space: on average, you find only one hydrogen atom per cubic meter. The deepest void in the cosmos, still ten times more extreme, can be found between galactic filaments, thread-like structures upon which galaxies concentrate (see box). This is where we might find a ‘true vacuum’, without the slightest trace of matter.

A polyvalent nothing

Low-pressure air has a wide range of industrial and commercial applications. For example, the mechanical force of vacuum is used in vacuum cleaners. This aspiration prevents contamination by microbes in food packaging and by dust during the etching of electronic circuits and industrial moulding. The vacuum almost entirely reduces the resistance to movement, hence the application to space probes and ultra-fast magnetic levitation train projects in dedicated tunnels like Swissmetro. The vacuum is also the best thermal insulator, used particularly in windows or thermoses. It’s also a good electrical insulator. We use it to our advantage in modifications to the physical-chemical properties of fluids at low pressure for distillation, freezing, industrial ovens, and even the sterilisation of surgical instruments with steam. The vacuum is necessary for testing space technologies on Earth.

While that directly observable matter – stars, galaxies, interstellar gas – adds up, there is also dark matter, which we cannot see but whose gravitational effects are evident. This invisible matter acts as a lens that distorts the trajectory of light, and measuring these distortions allows us to estimate its quantity: approximately five times more than matter.

Might the density of visible or dark matter decrease as one approaches the boundaries of the universe and reaches an extended void? “Probably not”, says Ruth Durrer, an emeritus professor of cosmology at the University of Geneva. “There are two possibilities: either the universe is finite, like the surface of a soap bubble. In that case, there’s no reason for the density to decrease. Or it’s infinite, like an endless cloth. But in that case, astronomical observations suggest that matter is infinite in quantity and is distributed uniformly throughout the cosmos.

The fate of the universe

A ‘true vacuum’ without any matter whatsoever is only found between isolated atoms out in space. In addition to visible matter and dark matter, cosmology describes a third component of the universe: mysterious dark energy. Its exact nature remains unclear, but this concept is necessary to explain the observation that our universe is expanding at an accelerating rate: the distances between galaxies are increasing more and more quickly with time. One possible form of dark energy is the cosmological constant: a density of energy that is repulsive, uniformly distributing it throughout the cosmos. It appears in the solutions of Einstein’s equations for a universe devoid of all matter, visible or dark, and corresponds to an energy that exists within the void. It’s as if the latter was making the universe grow, like air under pressure inflating a balloon.

And this energy of the void might well determine our distant future.

If the total density of the universe is below a certain threshold – including all matter as in Einstein’s scenario – then the cosmos will be like an infinitely unfolding cloth and will continue to expand forever. That’s the ‘big freeze’ scenario: a total darkness populated by isolated atoms and dead stars separated by increasingly greater distances, which will persist for eternity.

Ever since the Big Bang, the universe has been expanding, faster and faster. | Illustration: Michael Raaflaub

Another possibility is the ‘soap bubble’ universe in which its expansion slows down and then reverses under the effect of its own gravity, like a bullet fired into the air and which falls back, defeated by its attraction to ground. As the size of the cosmos decreases, the stars will approach each other, become consumed by black holes, and the universe will end in a ‘big crunch’, a form of big bang in reverse. For this scenario to pan out, it requires the density of the universe being greater than this critical threshold. And that dark energy is hundreds of times weaker than what we currently observe, says Durrer. “Which is why it’s so important to understand where the void gets its energy from”.

This quest takes us directly from the infinitely large to the infinitely small, to the heart of quantum physics, which describes the world of atoms and elementary particles. This includes particles of matter, e.g., electrons and protons, and particles of force, e.g., the photons behind electromagnetism. In this theory, every particle is the result of an excitation relative to the lowest energy level, which itself corresponds to the absence of particles. The energy of the void is not zero.

This is so, because in quantum physics “nothing is perfectly static”, says Durrer. A particle can’t be perfectly immobile at a specific location, according to Heisenberg’s famous uncertainty principle. A vacuum therefore receives energy from the incessant fluctuations of particles that could – potentially – exist. And even better: these fluctuations continuously create virtual pairs of particles, like an electron and its antielectron, whose lifespan is too short to be observed.

This quantum vacuum fills even the infinitesimal spaces between atoms, between electrons and their nucleus, or between quarks composing protons. The fact that it contains energy has been experimentally demonstrated many times, in the details of molecular forces or even in the Casimir effect, whereby a force generated in a vacuum pushes two simple metal plates against each other.

This quantum energy of the vacuum is a natural candidate for the cosmological constant – the energy of the vacuum described in a different context within Einstein’s general relativity. There’s a small but non-negligible problem: theoretical calculations predict an energy of the vacuum that’s much too high. Reference books even speak of ‘the worst theoretical prediction in the history of physics’. It is 10120 (one followed by 120 zeros) times greater than the established estimates based on astronomical observations – an inconceivably large discrepancy.

“This error isn’t at all surprising”, Durrer hastens to add. “Because this calculation should use a quantum theory of gravity, an approach that would describe both Einstein’s relativity and quantum physics simultaneously. We’ve been searching for such a theory for over a century, but so far without success”.

Is there anything around the universe?

Among the attempts to unify quantum physics and relativity, we find string theory. By considering spaces with an additional ten dimensions, it takes us even further away. In certain scenarios, “the disintegration of the void would see dimensions collapse onto themselves and disappear”, says Irene Valenzuela, a physicist at CERN. “These disappeared dimensions would give rise to bubbles of nothingness that would inflate, expand, and eventually take the place of our universe”. If string theory allows for a place for nothingness, this truly empty void remains abstract and has not yet been confirmed by any tangible observation.

Particle physics still has another surprise in store. The vacuum of our universe – and consequently everything it contains – is probably unstable. This is so, because the energy of the Higgs boson, which gives all particles their mass, might well have a more fundamental state. In such a case, the Higgs would eventually transition to this state, modifying its properties and, by ricochet, those of all particles in the universe. “In that case, there would be a strong chance of atoms no longer being stable”, says Durrer. Physics and chemistry, as we know them, would be impossible, and all matter – living beings, planets, and stars – would collapse into elementary particles and light.

Scale of emptiness. Order of magnitude of particles per cubic metre

This disintegration of the void would be ‘the ultimate ecological catastrophe’, wrote physicist Sidney Coleman in 1980. There’s only one consolation: the calculations estimate it won’t happen before 1065 years, which is much longer than the age of the universe (1010 years) and well after the last stars have burned out.

The void therefore appears to be essential, far from being ‘nothing’. But if approaches that allow us to explore it set forth myriad potential apocalypses of our universe, what do they say about its origins? Did ‘nothing’ precede it? Since time in our universe appeared along with space at the instant of the Big Bang, there was nothing before. There was no before.

The paradox is similar if we try to push the void around our universe: in principle, the universe includes everything that exists; there cannot therefore be anything outside of it. The concept of ‘nothing’, absolute vacuum or nothingness, remains delicate. “It’s tricky”, says le Bihan. Nothingness represents the ontological void. If there were such a nothingness ‘next to’ our universe, it would have to be locatable. But that’s not consistent with its definition, which is not only the absence of all matter and energy, but also of all spatial or temporal relationships. In this sense, I’d say that nothingness doesn’t exist. At least, not in our universe.