Feature: Much ado from nothing

And there’s always something

A text that dissolves itself. And a work of art that assumes meaning only when it is destroyed. We look at our how literature and art can help us to experience absence.

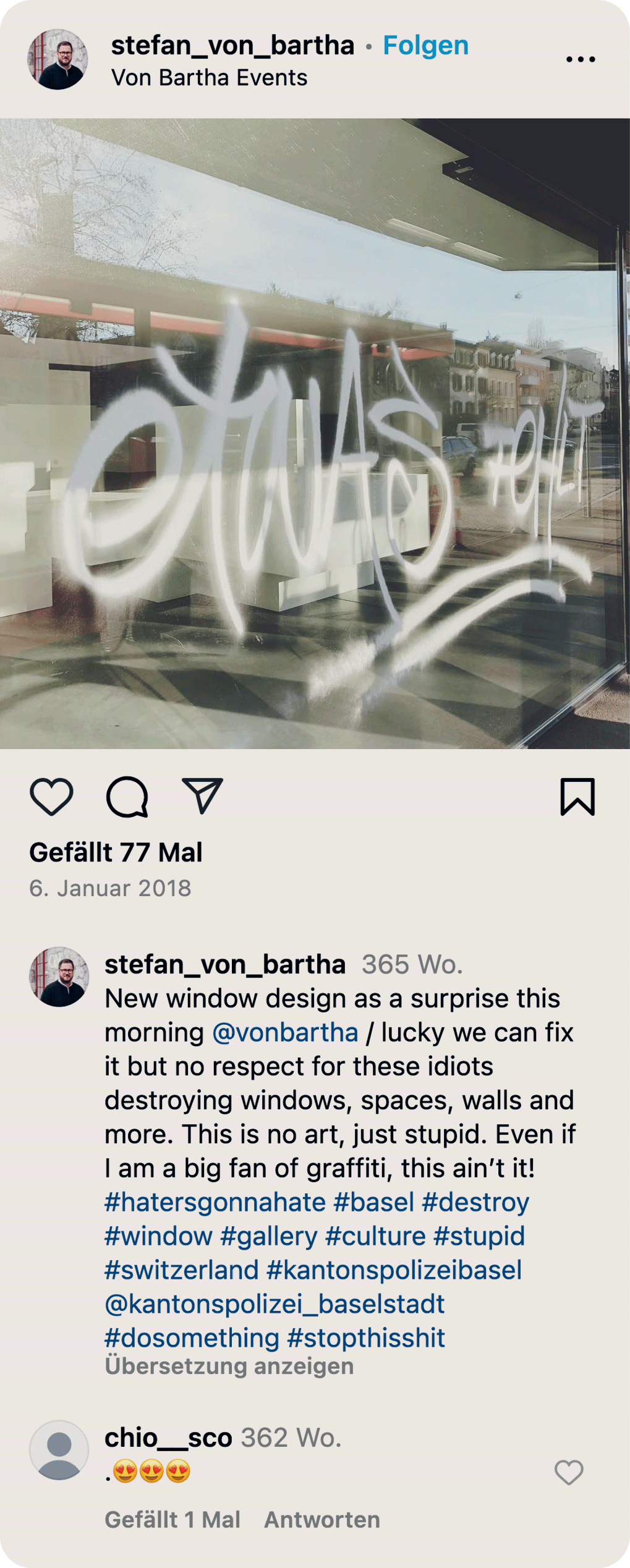

An Instagram post by Stefan von Bartha, put online on 6 January 2018. | Source: Von Bartha Gallery

“First a kind of erasure had to take place”

“This graffiti tag can’t be seen any more today. The picture is one of the very rare photos of works by the artist Florence Jung. The story behind it is this: On 6 January 2018, an employee of the Basel gallery Von Bartha discovered this writing on its façade. The owner of the gallery, Stefan von Bartha, had been travelling at the time and was extremely annoyed when he was told about it. He shared the photo and his irritation at it on Instagram, and two days later he had the graffiti removed. But now let’s rewind the story for a moment.

“A few months earlier, Jung had agreed to exhibit a work at the Gallery, with one condition attached: she wouldn’t inform the gallerist about it until her work had been realised. But she assured him that he would recognise it once it was in place. She then commissioned a graffiti artist to spray the tag overnight. In an e-mail dated 8 January, the artist explained to von Bartha that her exhibited work comprised the graffiti (since removed) and a media release. This is the first instance here where something is ‘missing’: initially, it was the interpretation of the work, its context, that was absent. So there was already a kind of emptiness, a ‘non-presence’ involved. And ultimately, to complete the realisation of the work ‘Jung 56’, a kind of erasure had to take place.

“‘Jung 56’, like all works by this artist, is hyper-conceptual. In this case, she’s playing with states of invisibility, with perceptions and situational contexts, with a rejection of materials and media. This also involves her enduring the emotional tensions that it triggers. You can even view ‘Jung 56’ from the perspective of the so-called performative paradigm. Here, the act of executing the artwork overnight would be the performance, the graffiti its physical remnant that signifies the absence of the performance. The removal of the tag then doubly confirms its disappearance.

“But it goes even further than this. Jung works with pictorial refusal. She does not want any official images, not even of herself. Today, performative works are often associated with a unique event. When this event is no longer present, art institutions try at exhibitions, biennials and festivals to fill this void with documentation, objects and photography, with the whole material culture.

“Jung does the opposite. She lets us experience emptiness in a world flooded with images, media, self-representation. She stands against this ‘horror vacui’ and says: ‘I don’t want this. I want a deep engagement with silence’. This attitude in turn directs our attention to other forms of cultural transmission, such as storytelling or sharing experiences.

“There have been at least two other manifestations of this work, one of which was on the Greek island of Anafi. As it was unintentionally associated with the death of a local resident, it had to be painted over quickly. However, later visitors reported that its statement ‘something is missing’ still shone through the layers of paint. It’s a wonderful metaphor – both for the many layers of Jung’s work and for the fact that it’s in a process of disappearing but is never really invisible. Emptiness per se is impossible. There’s always something there”.

The prose sketch ‘Wanting to be an Indian’ was included in Franz Kafka’s first-ever publication, ‘Betrachtung’ (‘Observation’), in 1913.

Wanting to be an Indian

If only I were an Indian, ready at any moment, if only I were on my galloping horse, leaning into the wind, trembling repeatedly as I passed over the shuddering earth until I let my spurs go because there weren’t any spurs, until I cast off the reins because I had none, and barely saw the land ahead of me as a smoothly mown heath, without a horse’s neck and a horse’s head before me.

“This text is a vanishing act in words”

“When you talk of nothingness, you’re essentially talking of something that isn’t. For talking isn’t nothing. But literature can attempt to make nothingness a topic of discussion. Or at least make it tangible. This text by Franz Kafka attempts to do just this. He gives us an image: the desire to become an ‘American Indian’. It’s a desire to be free. However, this ideal of free Native Americans (as we would call them today) is culturally determined. The desire for freedom becomes attached to it. But then the image starts to disappear from the text itself: the spurs, the reins, the horse’s neck, the horse’s head.

“This desire frees itself from its own culturally coded image. And with that, the text falls silent. But if the image of this desire for freedom disappears, what remains of it? This desire loses all concrete form, and the subject of the desire moves into a shapeless space, into an utter void. In other words: it disappears into nothingness. As a reader, I get a sense of this. I don’t disappear into the text myself, but it takes me quite deep into an experience of nothingness.

“In essence, this text is a single great act of disappearance. But it also doesn’t really allow this to happen, either. There is a second possible reading here: Historically, Native Americans didn’t use spurs to ride. That could just be a mistake. But the smoothly mown heath fits even less. A prairie is not a heath. These incongruous elements dismantle the desire for freedom: you’re not an Indian after all! Give up this desire for freedom! And this is also where the text breaks off. One can now bring these two readings together. The incongruous elements curb the desire for freedom and so prevent the subject from disappearing. This is because his cultural imprint is still there, which cannot merge into nothingness at the same time.

“But if this imprint is still there, then it is trapped in the world from which it would actually like to escape. In Kafka, this world always comprises societal constraints, institutions and norms. So there isn’t really any great disappearance after all. In my opinion, this text doesn’t decide in favour of one thing or another, but instead maintains a precise tension between a desire and the impossibility of fulfilling it.

“Kafka’s characters are often about to be destroyed by threatening forces. In the novella ‘The judgement’, for example, a son is sentenced to death by his father. In the novel ‘The trial’, the character is arrested and killed at the end. In the short story ‘In the penal colony’, the main character is killed in a machine. And so on. The forces to which the subject feels exposed always have the potential to destroy. So here, too, we have a form of nothingness.

“Incidentally, Kafka wrote a will for his friend Max Brod, instructing him to burn his work after his death. That was nothing more than an injunction for the author’s self-destruction. Another attempt at liberation. Another desire that wasn’t fulfilled. Kafka’s work did not disappear into nothingness. Instead, it became the most discussed corpus of German literature in the 20th century”.