Hiding green bugs in plain sight

The shimmering colour effects we see on many insects are not the result of pigments, but of special nanostructures in their body. A research team led by Bodo Wilts at the University of Fribourg has now discovered how the flower chafer from Indonesia (Chalcothea smaragdina) is able to produce its metallic green colour. They investigated the chafer’s chitin exoskeleton using electron and atomic force microscopy, and found a helicoidal structure in the outermost layer. This so-called exocuticle has roughly 70 layers of the finest fibres (micro-fibrils) on top of each other, staggered at regular intervals. “It’s precisely this arrangement that is needed to reflect a single, unique colour – in this case it’s green”. When light is reflected off it, it adopts a specific direction of oscillation, known as being ‘circularly polarised’. A grate-like structure on the surface of the exocuticle also helps to mitigate the reflection of non-polarised light. The researchers have also shown that when viewed through a polarisation filter, the chafer appears even more luminescent. Many insects can perceive this polarisation of light, but birds and mammals can’t. “By creating polarised light, the chafer probably catches the eye of others of its species, while at the same time remaining camouflaged from predators”, says Wilts. Wilts now wants to recreate the chafer’s helicoidal structures in the lab. This could make it possible to produce paints that are more resistant and healthier than those that are pigment-based. But it is also conceivable that they could help to create security features invisible to the naked eye for use in passports and on banknotes. Simon Koechlin CC BY-NC-ND

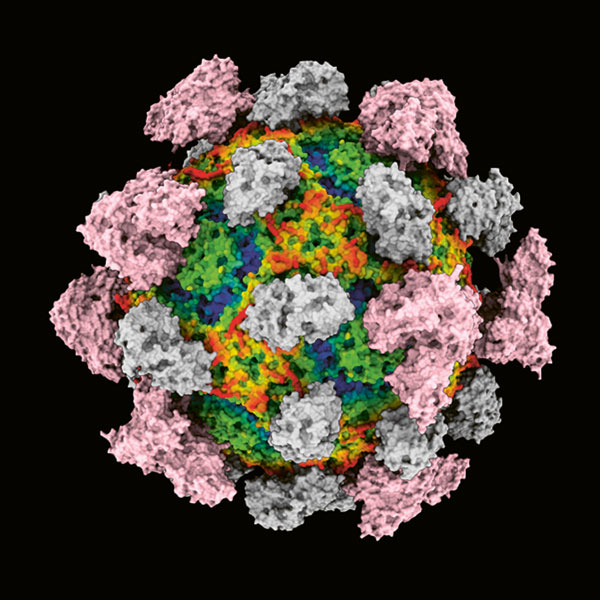

Nanostructures in the flower chafer’s exoskeleton are responsible for its luminescent green colour. | Image: Bodo Wilts

The shimmering colour effects we see on many insects are not the result of pigments, but of special nanostructures in their body. A research team led by Bodo Wilts at the University of Fribourg has now discovered how the flower chafer from Indonesia (Chalcothea smaragdina) is able to produce its metallic green colour.

They investigated the chafer’s chitin exoskeleton using electron and atomic force microscopy, and found a helicoidal structure in the outermost layer. This so-called exocuticle has roughly 70 layers of the finest fibres (micro-fibrils) on top of each other, staggered at regular intervals. “It’s precisely this arrangement that is needed to reflect a single, unique colour – in this case it’s green”. When light is reflected off it, it adopts a specific direction of oscillation, known as being ‘circularly polarised’. A grate-like structure on the surface of the exocuticle also helps to mitigate the reflection of non-polarised light.

The researchers have also shown that when viewed through a polarisation filter, the chafer appears even more luminescent. Many insects can perceive this polarisation of light, but birds and mammals can’t. “By creating polarised light, the chafer probably catches the eye of others of its species, while at the same time remaining camouflaged from predators”, says Wilts.

Wilts now wants to recreate the chafer’s helicoidal structures in the lab. This could make it possible to produce paints that are more resistant and healthier than those that are pigment-based. But it is also conceivable that they could help to create security features invisible to the naked eye for use in passports and on banknotes.

Simon Koechlin