How Renaissance publishers invented the novel

In an attempt to compete with books written in Latin, the publishers of the Renaissance period actually defined the canons of the Romanesque genre.

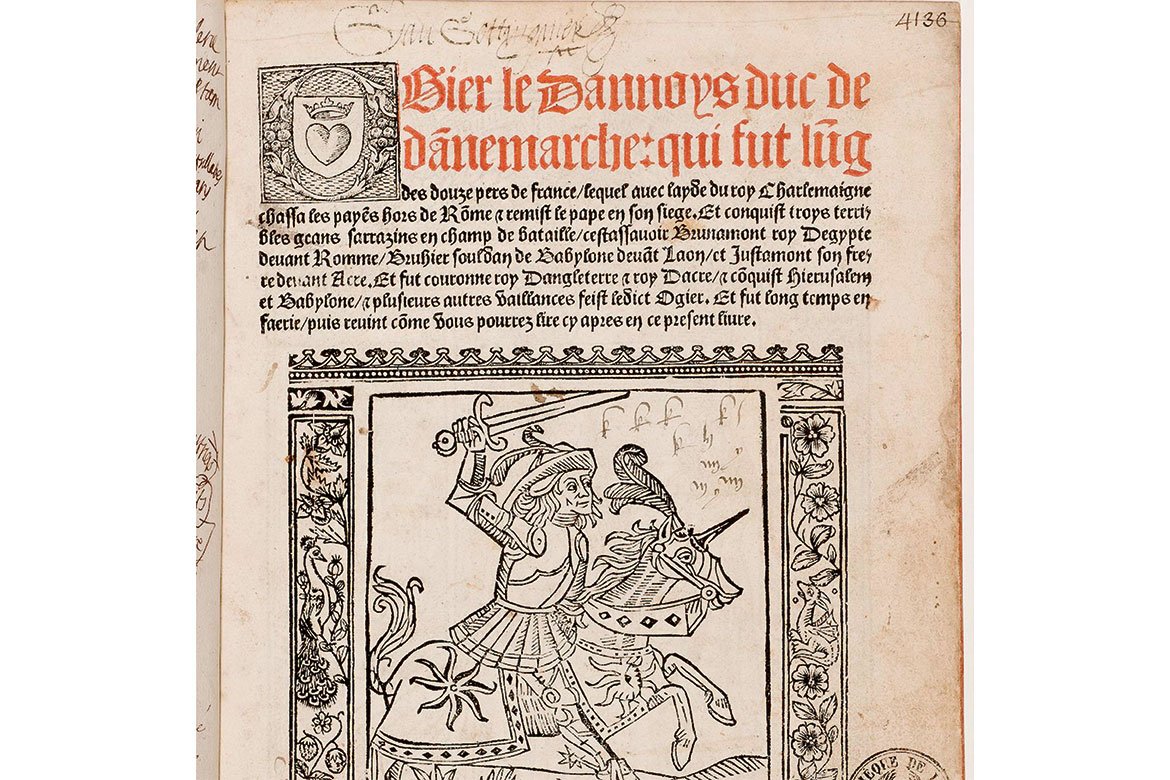

French texts were in demand in the 15th century. This led to the invention of the chivalric novel | Bibliothèque Nationale de France

It’s unlikely that anyone reading a novel stops to think about how the genre originated with Renaissance book printers. But it’s true. It started out as a trade practice, dating back to the appearance of the first printing presses in France around 1470. The goal was to compete with books written in Latin imported from Germany and Italy. But “the publishers then identified a niche: the vernacular”, explains Gaëlle Burg of the Institute for French and French Studies at the University of Basel, and “they began to call urgently for works in French”. Burg’s field of study is the advent of the chivalric novel as a literary category between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The publishers drew on medieval chivalrous texts and reformatted them for their readership: setting them in prose, reworking the language and introducing new iconography. It involved changes to both substance – shifting from medieval symbolism and motifs of courtly love to stories revolving around warlike exploits, and appearance – replacing the Roman lettering with Gothic and dividing the text into chapters. Interestingly, the concept of a title page also originates here.

“These book printers created a certain number of broad characteristics that would lead to the delimitation of a general category – the chivalric novel – based on distinct medieval literary forms”, says Burg. Her work involved analysing the changes in a corpus of five works, stretching from the first handwritten editions to those printed in the French publishing hubs of the 16th century.

In total, some one hundred works became part of a re-emergent literature. Books describing knighthood reached their peak around 1540, but despite their subsequent decline, they were reborn as part of the foundations of the genre of the romantic novel.