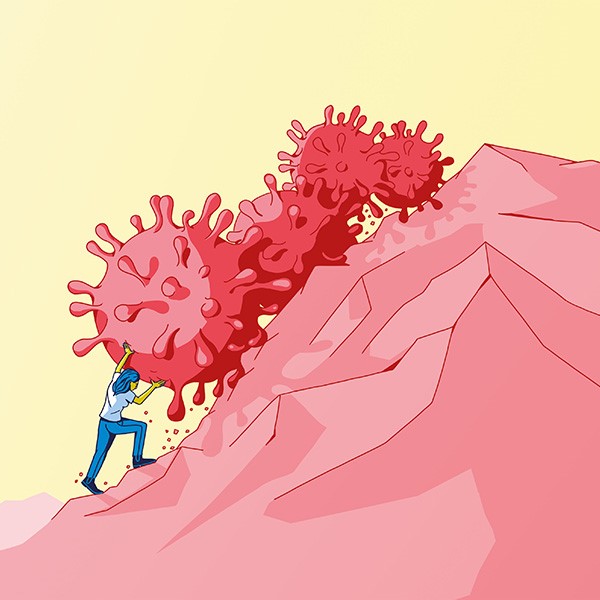

Never-ending pain

Chronic pain cannot be completely cured. That’s why researchers are feverishly hunting for new active substances. Their findings don’t promise any big breakthrough, but they could help to alleviate suffering.

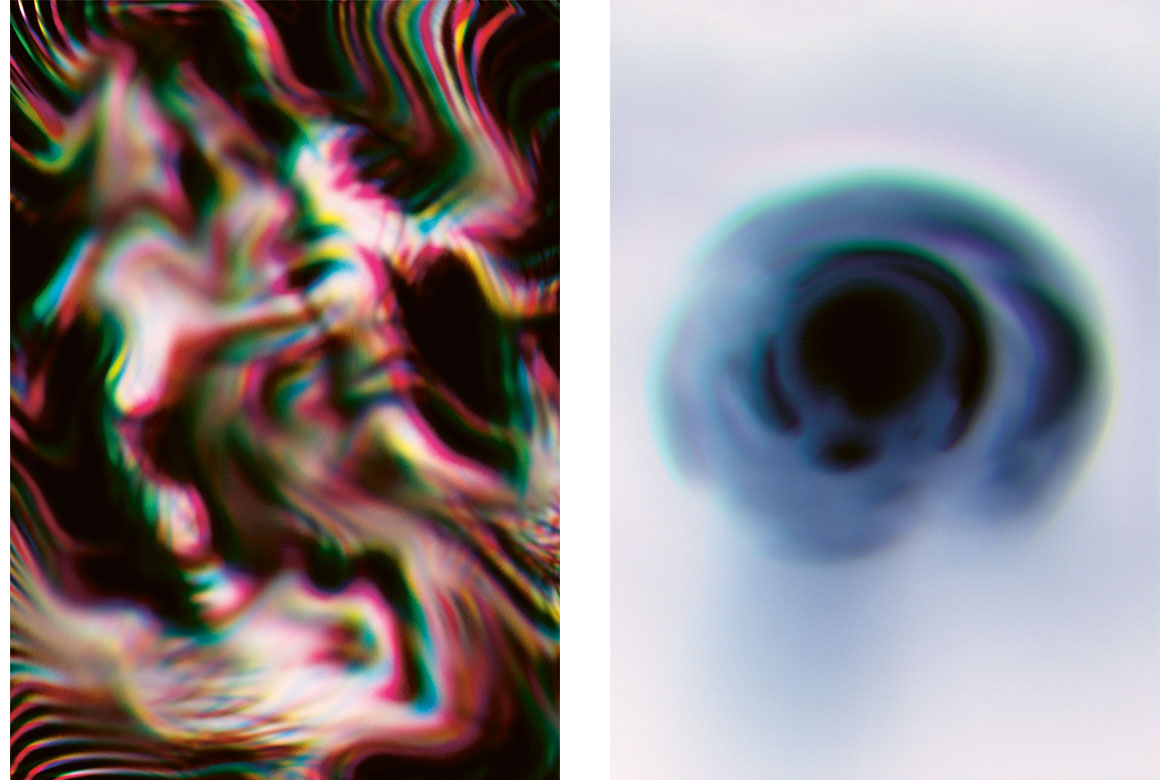

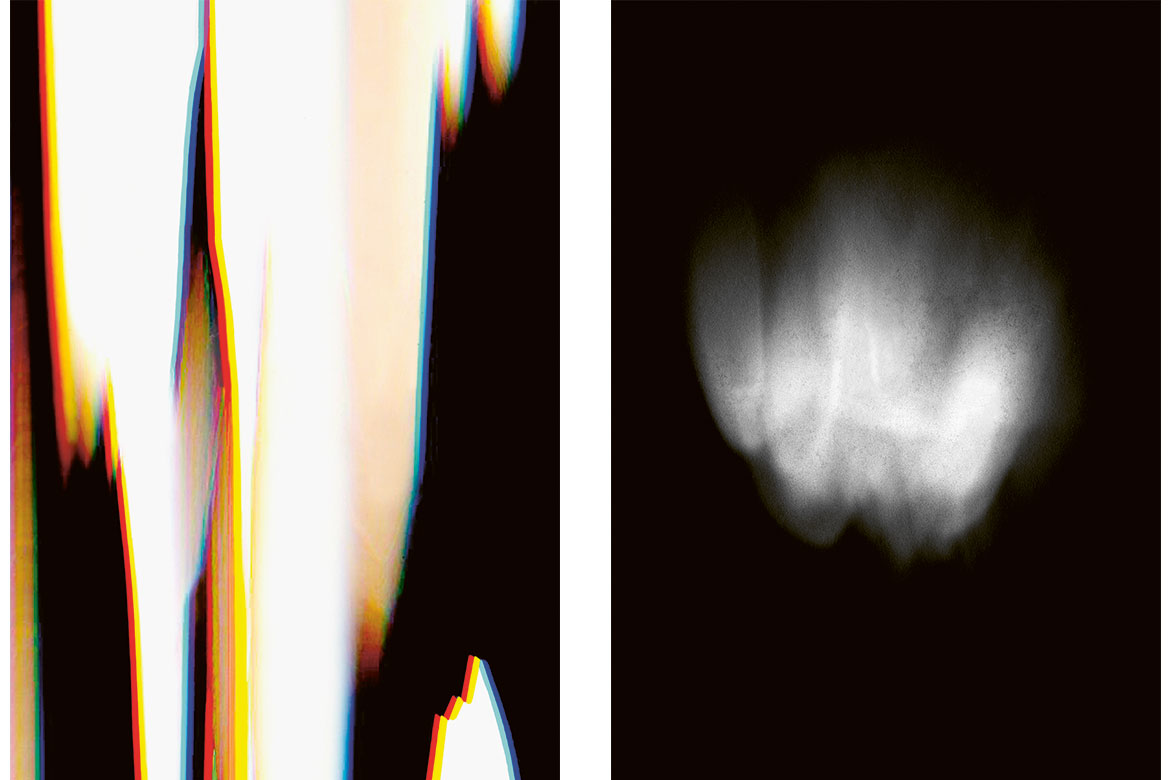

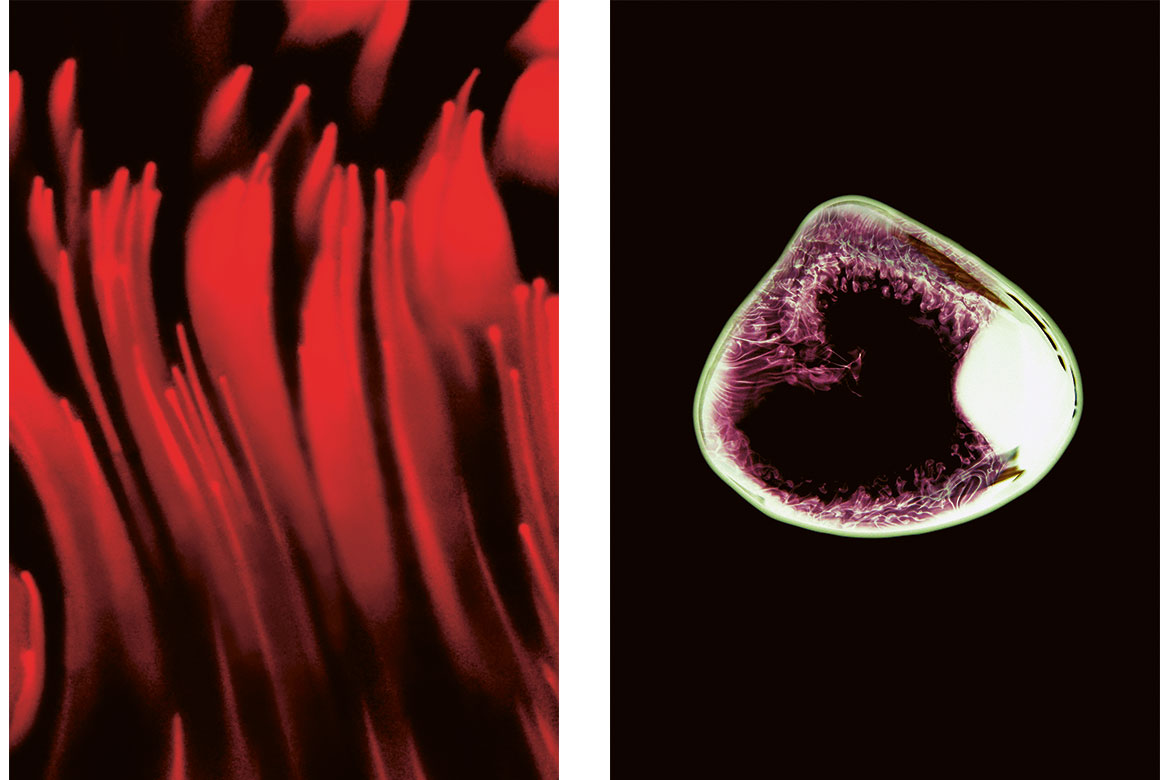

Here two people describe their pain using ‘dolography’ (see more below). The method was developed by two graphic artists from the Bern University of the Arts and a doctor from the Inselspital. | Images: Affolter/Rüfenacht

Migraines, toothache or lumbago: anyone racked with pain wants nothing but for it to go away as quickly as possible. Usually, the pain does indeed subside after a brief while – but sometimes it becomes one’s constant companion. If it lasts longer than three to six months, we speak of chronic pain. Some 20 percent of the Swiss population suffers from it, though to varying degrees of intensity. “Long-term, severe pain has a massive, adverse impact on life”, says Konrad Streitberger, the head of the Pain Centre at the University Hospital of Bern (Inselspital).

Into a vicious circle

Chronic pain usually starts with a specific trigger in the body, such as a slipped disc, a nerve injury or an illness such as multiple sclerosis. But chronic pain can also have mental and social causes that are mutually reinforcing. “Those affected enter into a vicious circle”, says Streitberger. Their pain means they are barely able to move, can’t work any more, and become depressed. This in turn affects their social life, which merely intensifies their mental and physical pain.

Left: “This picture shows the pain in my back: an aching pain that radiates from my neck to my coccyx”.

Right: “A dull, diffuse pain in my forehead that radiates slightly upwards”. | Images: Affolter/Rüfenacht

In order to take all these factors into account when treating chronic pain, specialist centres – such as that at the Inselspital – take a multimodal approach. Today, this is the gold standard in therapies for chronic pain. The patients are treated not just by doctors, but also by physiotherapists and psychologists. Nevertheless, only a few people are able to see their pain reduced by more than 30 to 50 percent. “There are more and more complicated cases in which patients are already taking opiates in high doses, and where we can’t make any progress with current therapies”, says Streitberger.

This is why there is an urgent need for new treatments. What’s important is developing new medicines. Today’s painkillers – such as ibuprofen, diclofenac, and opiates in the case of severe pain – are unsuited for long-term therapies because they have side-effects and/or can result in dependency. Or, worse still, they simply don’t work. “This is because chronic pain can have different neurobiological causes”, says Isabelle Decosterd, who runs the Pain Centre at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) and researches also at the Faculty of Biology and Medicine at the University of Lausanne.

Fire in the nervous system

While acute pain is an important warning signal for the body, chronic pain has lost this function. “It’s useless for the body”, says Decosterd. It occurs when acute pain is too intense and lasts too long. This results in a long-term sensitisation and hyperexcitability of the nervous system, both in the peripheral nerves and in the spinal cord and brain, creating a kind of ‘pain memory’. Stimuli that don’t actually cause pain can then be experienced as painful – even being stroked with a feather. Or a pain can suddenly occur without any recognisable trigger.

Left: “This is the feeling in my legs: a nervous pain that radiates downwards”.

Right: “A static, isolated pain”. | Images: Affolter/Rüfenacht

All over the world, researchers are trying to find new drugs that can be used in a targeted manner against pain mechanisms, and thereby mute the hyperexcitability of the nervous system. The pain-perceiving nerve cells in the skin and organs are an important point of attack here – the so-called nociceptors. Decosterd and her team are also testing different approaches that are designed to block a specific sodium channel to the nociceptors. This would suppress the transmission of pain signals and prevent them from being perceived in the brain. They are testing on rats and mice in which they’ve severed specific nerves. This causes chronic pain, and they hope this will help them find a substance that shows the desired effect. The animal model developed by Decosterd mimics chronic nerve pain in humans and is often employed by researchers.

Marc Suter works in Decosterd’s team. Besides their work on nerve cells, he is also concentrating on their support cells – the so-called glia cells. These emit messenger substances that influence nerve cells and thereby contribute to the chronification of pain. If Suter and his colleagues are successful in modulating the activity of these cells, it will open up new possibilities for therapy, because until now no drugs have been able to influence glia cells specifically.

The research team led by Hanns Ulrich Zeilhofer at the University of Zurich is taking a different approach, focusing on the body’s own pain relief mechanisms. These involve inhibitory nerve cells in the posterior horn of the spinal cord that emit the neurotransmitters glycine and GABA (gamma-amino butyric acid). These bond to other nerve cells in turn, and prevent them from sending pain signals to the brain. In order to alleviate pain, Zeilhofer’s group is looking for substances that could activate this precise mechanism.

No miracle cure in sight

Despite promising substances being discovered time and again in laboratories all over the world, only a few new drugs actually reach the market. While most of them demonstrate pain-inhibiting effects in animal tests, they generally fail in clinical studies because they have severe side-effects on humans. This is why Lars Arendt-Nielsen is convinced that it’s not enough to look for new substances. He’s a professor at the Center for Neuroplasticity and Pain in Aalborg in Denmark, and President of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). “There’ll never be a miracle cure for pain”, he says. There are just too many formation mechanisms involved in the body for a single drug to offer a solution. This is why a holistic therapy is necessary that is geared to the individual patient.

Arendt-Nielsen is putting his hopes in better diagnostics that may pinpoint the individual pain mechanism in each patient. Because for one person the main problem might lie in hyperactivation, but for another the body’s own pain inhibitors might be too weak. If doctors were able to know our individual pain mechanisms, they could provide a more targeted therapy than has previously been possible.

Arendt-Nielsen also sees great opportunities in expanding multimodal therapies. He wants to put a greater emphasis on exercise programmes and on a patient’s self-management. Both are already important components of existing therapies. The goal is not to rid a patient of pain entirely – because in most cases this is impossible anyway – but to reduce it to a manageable degree. “What’s most important is to activate the patient so that they can exit their vicious circle”, says Streitberger. The therapy helps them to find a different way of dealing with pain. This can also include setting realistic goals. Such as one of Streitberger’s own patients, who wanted to be able to go to the opera again. “Being able to achieve that was already a great improvement in her quality of life”.

Claudia Hoffmann is a freelance science journalist and works for the WSL in Davos.