Feature: Belief in science

A mental game

A scientific discipline can be seen as a system of symbols, rather like a religion. Horizons Editor Judith Hochstrasser sketches out a mental game.

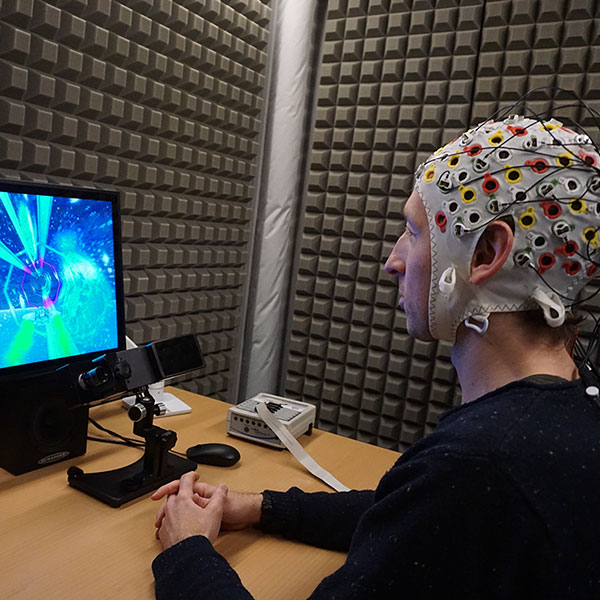

String theory or loop quantum gravity? When someone claims that one or the other is true, it’s a matter of belief, not factual knowledge. | Image: AdobeStock / fotoliaxrender

There are innumerable definitions of religion. An inspiring one was coined by the American ethnologist Clifford Geertz: “A religion is a system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing those conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic”.

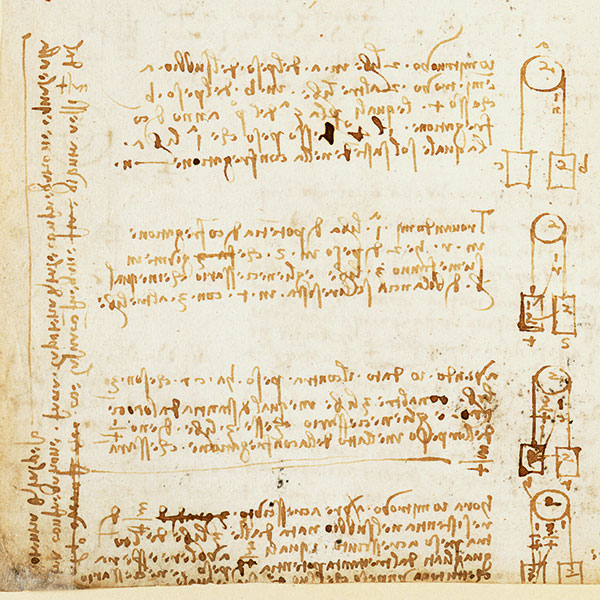

If we indulge in a mental game and test this definition on the sciences, it can open up new perspectives. Symbols to Geertz are “all objects, acts, events, features or relations that become the notion of any concept”. One important system of symbols is language. But everyday procedures and acts also have symbolic content. Systems of symbols are models of reality. Accordingly, a scientific discipline too can be regarded as a system of symbols made up of objects and acts – such as chemistry with its molecular models and its experiments. Or history, with its concepts and sequences of events.

An order of existence does not need to contain a god, but can be the acceptance of an objective structure that permeates everything. Certain scientific disciplines toy with ideas about such structures. Some physicists, for example, postulate a theory of everything – something that pervades the whole physical world. Historians proceed from the assumption that we cannot understand our present without our past, and that the past permeates everything.

But now comes the crucial point in this mental game of ours. According to our above definition, these conceptions of an order of existence are clothed in an “aura of factuality”. Can this also be applied to the sciences? Certainly not overall. But is a theory of everything as postulated by physicists something true, or just a theory? Do historians place the influence of the past above everything else? Or do they claim that it is only one important factor? What’s decisive for this mental game, this test, is this: does a scientist regard all-embracing conceptions of his discipline as hypotheses to be tested against reality, in order to acquire new knowledge? Or has he in fact begun to believe instead?