Feature: Cinema, fact and fiction

Scientists on set

Like their American colleagues, Swiss filmmakers seek the advice of scientists and scholars. This leads to a dialogue that is often inspiring for both parties. Examples include ‘Le Réformateur’ (‘The Reformer’), released in 2019, and ‘Electric Child’, currently in production.

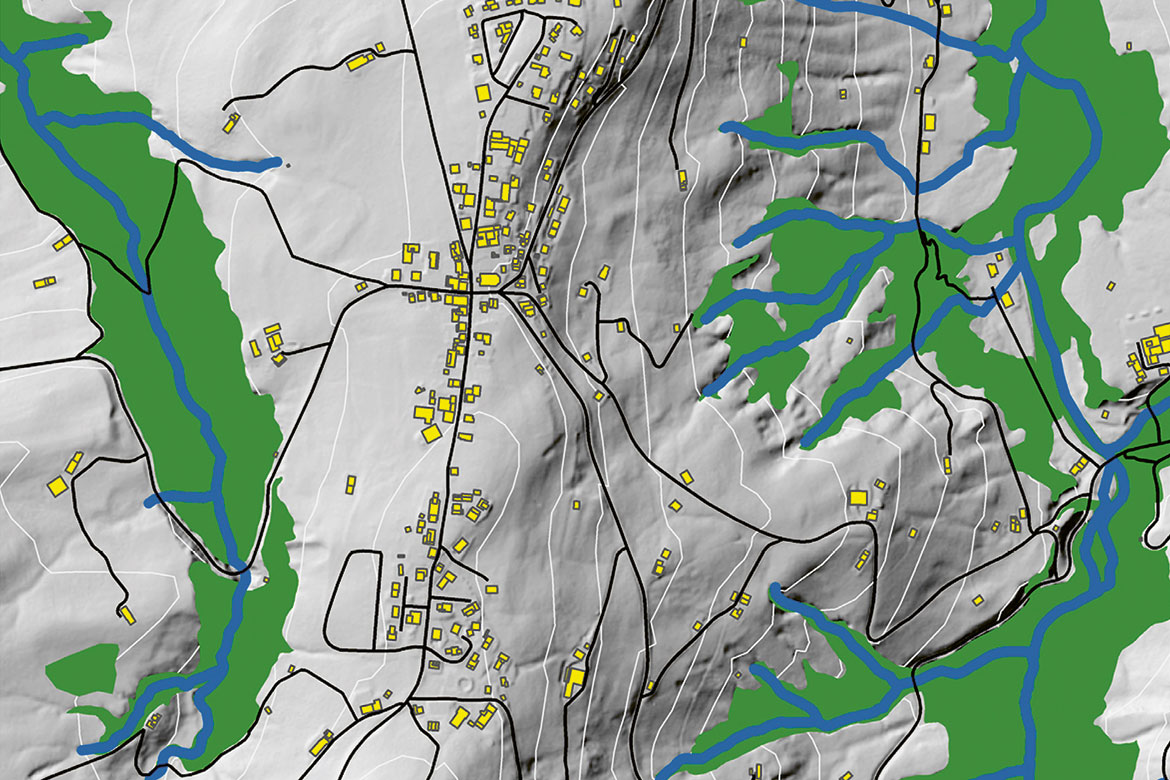

When setting up a scene, the visual aspect is the film crew’s priority. The fact that the result is close to the reality of its university setting is a bonus. | Photo: Michel Gilgen

For their film ‘The Reformer’, the Zurich director Stefan Haupt and the scriptwriter Simone Schmid consulted more than a dozen experts: theologians, historians, art and religion specialists. It was released in 2019 and traces the later life of Ulrich Zwingli, from when he settled in Zurich in 1519 to his death at the Battle of Kappel in 1531. “I wanted to create a portrait that was as close as possible to the historical sources, while at the same time portraying the spirit of the time and the tensions that ran through it”, says Haupt. “I also met pastors and visited monuments. This work was essential for me, because I felt a responsibility to produce a film that took current knowledge into account”.

As for Schmid, she did a lot of reading, from recent studies to Zwingli’s own correspondence. In particular, she did a lot of work on the character of Anna Reinhart, Zwingli’s wife: “I had to reconstruct her character from hardly any sources. To do this, I consulted specialists on women during the Reformation. Thanks to their knowledge, we were able to reconstruct a plausible character. That is, a woman who did not actively participate in her husband’s theological debates, but who was able to form an opinion and express it”. The readings and the exchanges with scholars fed her inspiration as scriptwriter. “You then go through a kind of distillation process to make it into a script. This involves giving up many elements, simplifying facts and sometimes adjusting them to the constraints of the dramaturgy, the production, the budget...”. Haupt says he gave up the idea of reconstructing a cemetery around Zurich’s Grossmünster, because the logistics involved would have been beyond his financial means. “Instead, I went to great lengths to remove the pews from the church so that I could film the standing mass crowd, as was the case at the time”.

Open-mindedness essential

In the end, the film is the result of a collective effort involving various professions, limited by their own constraints. It’s a world far removed from that of researchers. Rebecca Giselbrecht, a theologian at the University of Bern and a pastor, was particularly interested in the figure of Anna Reinhart. She was interviewed by Schmid and was delighted to have been contacted: “[Schmid] wanted to know in great detail what was going on in the minds of Zwingli and his wife, including details of their sexuality. I found her questions interesting and inspiring. We don’t come from the same world and I was willing to share my knowledge without knowing exactly what she would do with it. I had to let go”.

Meanwhile, Reinhard Bodenmann, a historian specialising in the 16th century, was somewhat hesitant when Haupt reached out: “Mainly because I was quite busy. Then there were some colleagues who’d told me the film might not be any good. But, anyway, I started reading the script, and I thought it had potential. That’s why I accepted the challenge”. He then spent more than 75 hours re-reading and annotating the script: “There were anachronisms, such as the scene where Anna’s son is upset by the death of a bird. At that time, the death of an animal wouldn’t have provoked the same reactions as it does today”. Bodenmann says that he wanted to pass on to the film team a certain working methodology and sought to introduce them to how people thought in the 16th century, so that they would not project their sensitivities onto the characters and dialogue of the past.

“I must admit that I was anxious before I saw the film in the cinema”, says Bodenmann. “I didn’t know whether the director and the scriptwriter had taken my comments into account. I knew that a historical film would emerge from the novel and that it was not a historical documentary. But I was afraid that my name would appear in the credits of a film full of mistakes”. At the end of the two-and-a-quarter hour screening, Bodenmann was relieved: “The filmmakers did a magnificent job, the result is coherent and they found excellent compromises. I give them a 5.9 out of six, because there are certainly small details that could have been improved, such as the ‘Hallo!’ (Ed., an expression that only appeared in the 19th century), which could easily have been replaced by a ‘Gruezi’! Haupt has succeeded in the difficult tasks of taking the audience back 500 years, of not speaking out for or against the Reformation, and of not turning Zwingli into a hagiographic figure”. Giselbrecht also has high praise for the film: “It gives a wide audience an insight into the Reformation. It has been appreciated by most of my colleagues, both scholars and priests”.

Haupt and Schmid were awarded honorary doctorates by the University of Zurich for the excellence of their work and were delighted with the reception their film received from specialists, even if some voices were critical of the costumes or the language. Schmid has come to accept that it is not easy for an academic to collaborate with a filmmaker: “There needs to be a certain open-mindedness and an attempt to understand how films are made. Above all, it doesn’t work unless you really aspire to a team effort”.

Scientific accuracy in a rather crazy fiction

Schmid won’t be contradicted by Andreas Steiner, a researcher specialising in artificial intelligence. He is currently working with the Zurich-based director Simon Jaquemet on the film ‘Electric Child’, which is due for release at the end of 2023. This sci-fi saga delves into the world of a computer professor who makes a pact with an artificial intelligence character to save his sick son. “I’m thrilled to be able to help the film grow in quality. I would like it to be enjoyable to watch, even for scientists”. Steiner has been talking to the director regularly for several weeks now. “These discussions are pleasant because he has excellent computer skills and his script is good. He is open and understands quickly. My role is really that of an advisor”.

For Jaquemet, having a scientific advisor is crucial: “I may be a geek and have a good level of computer knowledge, but I’m still an amateur... And I want my film to be as realistic as possible, because that’s what the audience expects”. In addition to Steiner, Jaquemet also worked with a doctor to describe the symptoms of the disease afflicting the character of the son. “We have to incorporate as much knowledge as possible before shooting. Afterwards there’s no time for anything”. We asked Jaquemet if he seeks scientific precision for educational purposes. “That’s not the primary objective of the film, which is more about relatively outlandish fiction. But if I manage to avoid any glaring or embarrassing mistakes, so much the better. Secondly, some of the artificial intelligence developments described may become realistic in the future. So if it provokes discussions among scientists or the public about the issues around the development of artificial intelligence I’d be happy”.

The ambition described here is naturally modest compared to productions like the 2014 release ‘Interstellar’ by the British-American director Christopher Nolan. It saw entire teams of scientists working to create the most precise images of a rotating black hole ever produced. “When teams like this work on a subject, it is not surprising that their results can influence other scientists”, says Steiner.

As far as Zwingli’s life is concerned, although the film ‘The Reformer’ has not directly influenced the work of specialists, it has provoked debate within the scholarly community. The film’s success in cinemas, particularly in German-speaking Switzerland, has enabled the general public to learn more about events in Zurich in the 16th century.